Two large-scale exhibitions in Qatar give a foretaste of the curatorial strategy in the Gulf emirate, whose ambitious museum-building programme marks its 20th anniversary next year. Qatar Museums (QM), led by Sheikha Al Mayassa, the sister of the ruling emir, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, was founded in 2005 principally to diversify the fossil-fuel dependent economy through cultural tourism.

MANZAR: Arts and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today (until 31 January) is at the National Museum of Qatar, Jean Nouvel’s crystalline desert rose in the capital, Doha. The survey on art from Pakistan spanning over 80 years, was devised by the future Art Mill Museum, whose national collection of global Modern and contemporary art since the 1830s was amassed over four decades. Aiming to show different regions’ art on an equal footing, it is due to open on the Doha waterfront in 2032, in a flour mill repurposed by the Chilean starchitect Alejandro Aravena.

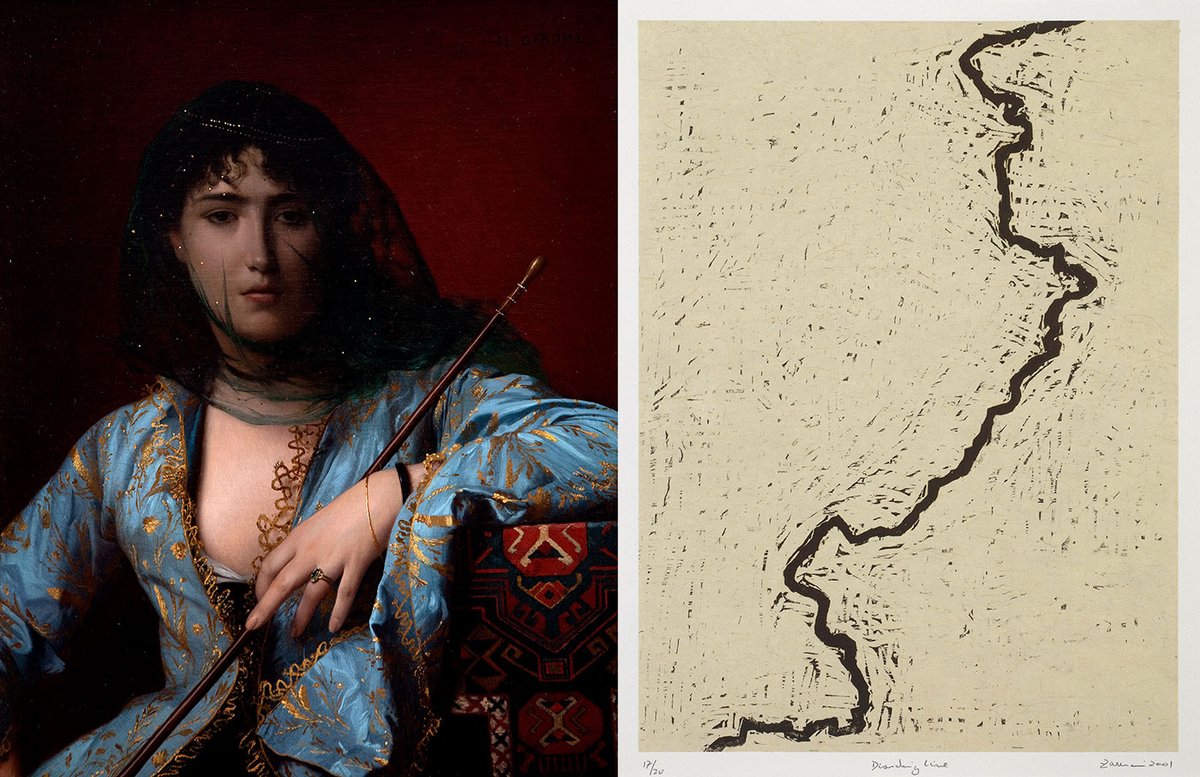

Over at Mathaf, the Museum of Modern Arab Art, Seeing Is Believing: the art and influence of Gérôme (until 22 February) raises another curtain. The Lusail (formerly the “Orientalist”) Museum is being built on Al Maha island, north of Doha, by Herzog & de Meuron to house possibly the world’s biggest collection of Orientalist painting and photography. Its bicentennial show on the 19th-century French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme (1924-1904) signals how it might contextualise this sometimes problematic art.

MANZAR (meaning view or landscape in Urdu and Arabic) brings together Pakistan-based artists whose work is seldom seen outside the country with prominent names in the diaspora. “Pakistan is so overlooked,” Catherine Grenier, the director of the Fondation Giacometti in Paris, and Art Mill’s director of concept, tells The Art Newspaper. Chosen to “reflect Qatar’s multicultural society”, the focus was made possible by a strategic partnership. The Pakistani prime minister, Muhammad Shabbaz Sharif, attended the opening during an official visit on trade, investment and security. Of 200 works on show, 130 are rare loans from Pakistan.

The loosely chronological exhibition ranges from pre-Partition painters such as Abdur Rahman Chughtai and Zainul Abedin to Naiza Khan’s video installation filmed off Karachi’s coast, Sticky Rice and other stories (2019)—a reminder of Indian Ocean trade and proximity to the Gulf. The traumas of “the long partition” of 1947 and 1971 (Bangladesh’s war of independence) are a conceptual thread, as are artists’ cross-border friendships, encapsulated in the Indian MF Husain’s pen portrait of the Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

Arif Mahmood, Baba Farid Ganj Shakar Urs (2008), from Manzar: Arts and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today at National Museum of Qatar, Doha Taimur Hassan Collection. Photographed by Arif Mahmood.

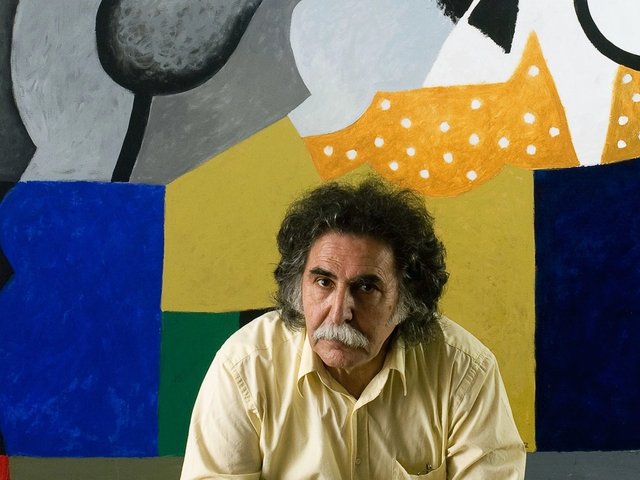

Fed by primary research and archival material, the show traces how Pakistani artists and architects acted in dialogue with, or diverged from, international art movements. Pakistan’s “embrace of modernism was only possible after formal decolonisation”, the artist Iftikhar Dadi said in a talk, as artists no longer had to “defend tradition”. Sadequain’s cactus-motif abstraction of the 1950s, and formal experiments such as “calligraphic modernism”, give way to a 1980s return to figurative painting and the 1990s urban vernacular of “Karachi pop”. The New Miniatures movement of Shahzia Sikander and Imran Qureshi is shown alongside historic miniatures from Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art. The Karachi-based co-curator Zarmeene Shah says a survey on this scale would not be possible in Pakistan, where “the spaces are not there”, nor the funds.

Disentangling histories

Rather than attempt MANZAR’s unified perspective, the Gérôme exhibition offers three distinct, at times competing, curatorial views. “Orientalist art is popular in the Arab world,” Julia Gonnella, the director of the future Lusail Museum, tells The Art Newspaper, “but problematic in the West.” The Lusail has broadened its core collection of 19th-century representations of the MENASA region to film, fashion and music related to cultural exchange, aiming to “disentangle the histories” and “revert the gaze”.

Though Edward Said never mentioned Gérôme, the artist’s Snake Charmer (around 1879) appears on the cover of the Palestinian-American academic’s Orientalism (1978). In the retro atmosphere of a Paris salon, Emily Weeks’ display makes a revisionist case for rescuing Gérôme from postcolonial scorn, charting his travels in Italy, Egypt and Turkey, the limits of French colonial power, the technical mastery of his academic style and the fabricated realism of his studio “bricolage”. His Veiled Circassian Lady (1876) was a Parisian model. A big influence on Hollywood, Gérôme was the “most reproduced artist ever in the 19th century,” owing to his art-dealer father-in-law, Adolphe Goupil.

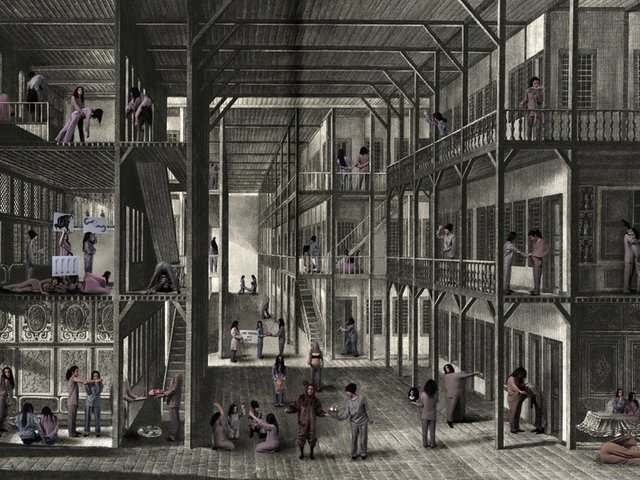

Sara Raza counters with 25 contemporary artists contesting misrepresentation, including Ergin Çavusolglu’s video installation of Roma musicians, Quintet Without Borders (2006). Before this, Giles Hudson views Gérôme in relation to early photography, and the exoticising use of saturated colour. At its most compelling, the show hints at Gérôme’s painterly illusionism as a precursor of today’s deep fakes. However, one work, Harem (2009) by the Turkish artist İnci Eviner, was pulled from the exhibition by the ministry of culture before the opening.

The research group Forensic Architecture’s first solo show in the Gulf, Everything is red and grey, was also scheduled to open at Mathaf on 2 November. Investigations in the “context of Israel’s genocidal military campaign in the occupied Gaza Strip” were to be shown with others of “regional significance”, on “themes of violence against migrants, migrant labour, and surveillance”. However, the exhibition was postponed. At the time of writing, no opening date had been announced.