From the Heart to the Hands: Dolce & Gabbana

Grand Palais, Paris, 10 January-31 March

Art meets fashion in a blockbuster show at the Grand Palais celebrating the enduring Italian fashion house Dolce & Gabbana. The exhibition, curated by Florence Müller—a former professor at the French Institute of Fashion in Paris—will include more than 200 creations by designers Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana, who founded the fashion house in 1985. “Unfolding over a series of ten rooms covering 1,200 sq. m, the show explores the brand’s unconventional approach to the world of luxury … embracing humour, irreverence and subversion,” according to an exhibition statement.

Works of art are included throughout, including a series of paintings by the French-US artist and actress Anh Duong. “She has created these works by following Dolce & Gabbana’s Alta Moda and Alta Sartoria collections in recent years,” Müller says. “While her work is focused on self-portraits, she pictures herself wearing their dresses in imaginary and surreal landscapes, reflecting the rich Italian heritage of the two designers.”

Müller adds that Dolce & Gabbana are “constantly inspired by many aspects of Italian art and craft, which are examined in the show for the first time”. The exhibition will draw on artistic traditions and crafts, such as Orsini Venezia, a furnace in Venice that has produced gold-leaf mosaics since 1888.

The show will also explore the influence of other artists and artisans on the design duo, such as Barovier & Toso, a famed Venetian glassmaker founded in the 13th century. Dolce & Gabbana have also worked with Salvatore Sapienza, who restores and decorates Sicilian carts, and the Bevilacqua brothers—Sicilian siblings known for their innovative ceramics (Dolce was born and raised in Sicily).

“The scenography of each section is inspired by Italian history of art, opera, the art of stucco, architecture—especially the Renaissance-era Palazzo Farnese in Rome—Baroque interior design, the Temple of Concordia in Agrigento [constructed around 430BC in Sicily],” Müller says. The Paris show is similar to an earlier version that launched at the Palazzo Reale in Milan earlier this year, except for two sections that were specially adapted for the Grand Palais, Müller adds.

The Australian artist Leigh Bowery, pictured here by Fergus Greer, is the subject of an “eclectic and immersive” exhibition at Tate Modern

© Fergus Greer. Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery

Leigh Bowery!

Tate Modern, London, 27 February-31 August

There are few realms of creativity that the work of Leigh Bowery (1961-94) did not touch. The boundary-pushing Australian was an artist, performer, club kid, model, television personality, fashion designer, musician and queer icon, and this survey will explore every aspect of his career and its various impacts on contemporary art and culture.

Bowery was often described as a living art object: “He reimagined clothing and make-up as forms of sculpture and painting, tested the limits of decorum and created a new form of performance art to explore the body as a shape-shifting tool with the power to challenge norms of aesthetics, sexuality and gender,” according to a press statement. His work was provocative and controversial: one of his most notorious performances involved strapping his wife and collaborator Nicola Rainbird—who now manages the artist’s estate—to his chest, upside down, and “giving birth” to her on stage.

The exhibition at the Tate will be the first to bring together Bowery’s costumes alongside paintings, photography and videos showing the breadth of his work. It will also include a newly commissioned music and video installation by the film-maker and DJ Jeffrey Hinton inspired by Taboo, a club night that Bowery created in 1985 which invited people to transform themselves and explore their identities.

The Tate will also present the video What’s Your Reaction to the Show? (1988), made by the artist Dick Jewell. The film captured people’s responses to a voyeuristic five-day performance at London’s now-defunct Anthony d’Offay Gallery, where Bowery dressed up in front of a two-way mirror, allowing viewers to watch him while he could only see himself. Other works in the show include several of the portraits that Lucian Freud made of Bowery, who became a close friend and muse to the painter, and photographic portraits by Nick Knight and Fergus Greer.

The exhibition will end by exploring Bowery’s band Minty, which allowed him to combine the many aspects of his art. A monograph with new photographs of all the costumes held in the artist’s estate will accompany the show.

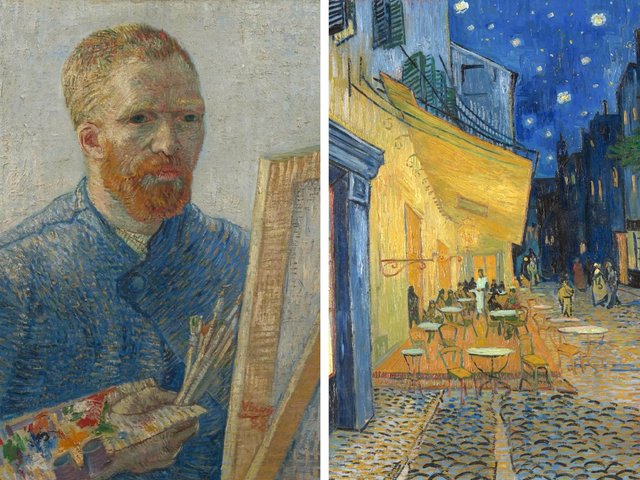

The Van Gogh Museum and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam are collaborating on a landmark show by Anselm Kiefer that pays tribute to his fascination with Van Gogh; it will feature, among many other works, 2019’s The Starry Night

© Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Georges Poncet

Anselm Kiefer: Where Have All the Flowers Gone

Van Gogh Museum and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 7 March-9 June

Vincent van Gogh and Anselm Kiefer—two artistic titans separated by time but deeply connected through practice—are being brought together in an ambitious, two-venue show that’s opening in Amsterdam in March. Anselm Kiefer: Where Have All the Flowers Gone (Sag mir wo die Blumen sind), which is split between the Van Gogh Museum and the Stedelijk Museum, seeks to both highlight Kiefer’s decades-long fascination with the Dutch artist and offer a fresh view of his broader artistic development.

The exhibition highlights Kiefer’s fascination with the Dutch artist and offers a fresh view of his broader artistic development

The event, which is the first joint project of its kind between the two museums, has been put together in close collaboration with Kiefer, who has created a host of new works for the exhibitions. It is intended to be seen as “one show”, says the Van Gogh Museum’s head of exhibitions Edwin Becker, although the two parts will be distinct in their focus.

At the Van Gogh Museum, exhibits will include drawings Kiefer made on a trip from the Netherlands to Belgium and France as a teenager, retracing Van Gogh’s footsteps. There will also be works by Kiefer that directly respond to the Post-Impressionist, including the never-before-exhibited The Starry Night (2019, pictured above), which evokes Van Gogh’s nightscape in a mixture of acrylic, straw, gold leaf, wood and more. The most “striking element of Kiefer’s work in relationship with Van Gogh,” says Becker, “is that he’s not so much interested in the myth of the artist. It’s more that he is struck by the compositions and the construction of the picture plane—that’s what he’s referring to all the time.” Corresponding paintings and drawings by Van Gogh, he adds, will also be on view.

The Stedelijk, meanwhile, is bringing out every Kiefer work in its collection for the first time. These will range from films to well-known canvases such as Innenraum (Interior) (1981), depicting the mosaic room of the now-demolished New Reich Chancellery in Berlin, a symbol of Nazi dictatorship. The Stedelijk will also house the exhibition’s “key” work, Becker says: a new 24m-long installation that will surround the museum’s historic staircase and consist of materials including paint, clay, dried rose petals, gold, costumes and Second World War uniforms. This work shares the title of the show, which references an anti-war song from 1955 written by Pete Seeger and made popular by Marlene Dietrich.

Later in the year, the Van Gogh Museum will collaborate with the Royal Academy of Arts in London on an adapted version of the show.

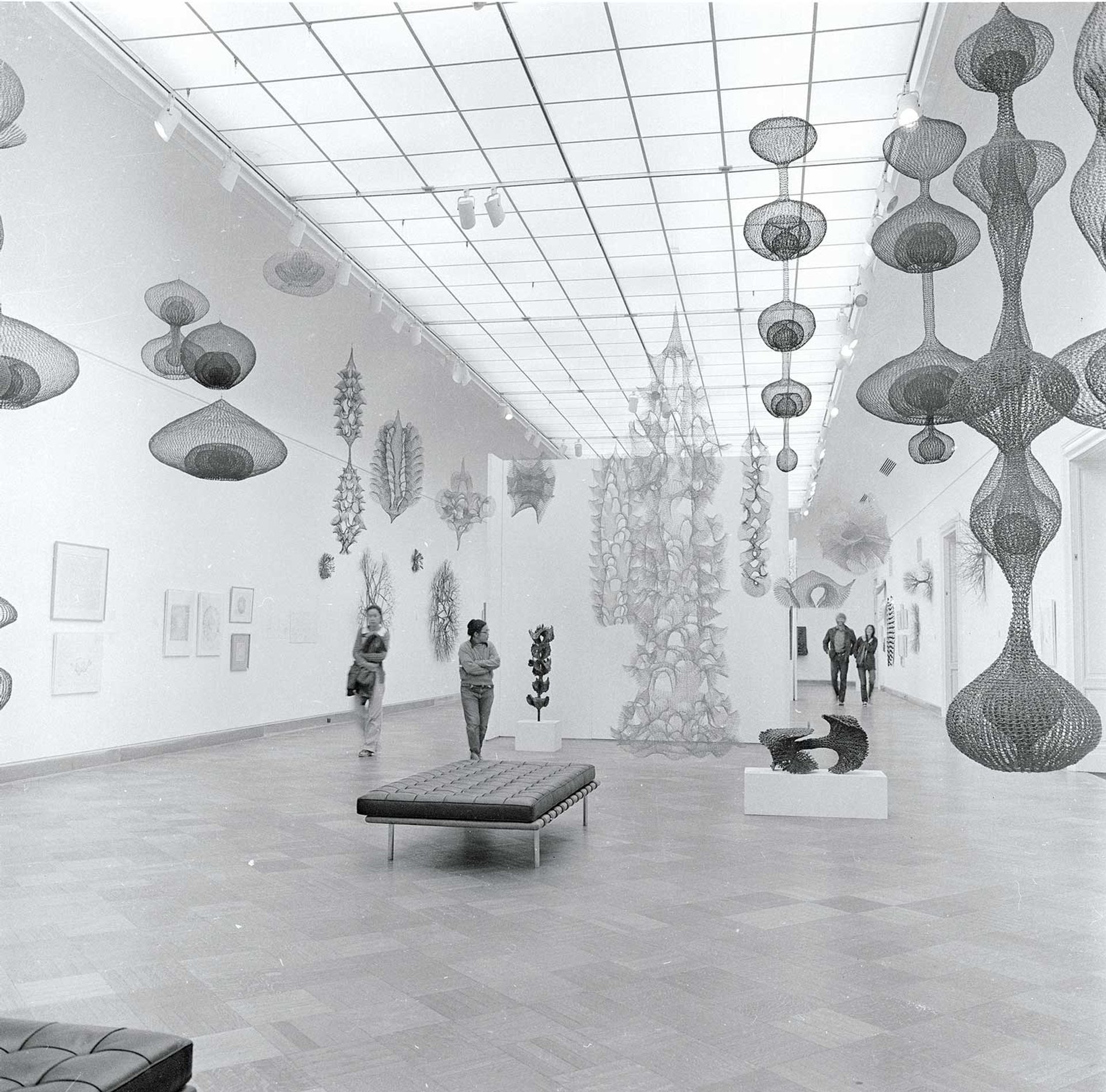

A major retrospective of the American sculptor Ruth Asawa will be travelling across the US this year, starting in San Francisco; pictured here is Asawa (second from left) alongside visitors to her exhibition Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective View, which ran at the San Francisco Museum of Art (now SFMOMA) in 1973

Photo: Laurence Cuneo

Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 5 April-2 September

Museum of Modern Art, New York, 19 October-7 February 2026

When US president Joe Biden posthumously awarded Ruth Asawa a National Medal of the Arts in October, the White House cited the fabled artist and educator’s “groundbreaking Modernism” as well as her “championing art for everyone”.

Throughout 2025, audiences on both the East and West coasts of the US will finally get to immerse themselves in Asawa’s exultant, filigree work in the first national and international museum survey dedicated to this quietly extraordinary artist.

Asawa was born in rural California in 1926. During the Second World War, she was detained, along with her family and others of Japanese descent, in internment camps. Her family were separated into different camps, with Asawa’s located in Arkansas. After the war, she attended Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where she studied under the German-American artist Josef Albers and the US architect Buckminster Fuller (whose works, among those of her peers, will also be on display at the show).

In an interview in 2002, she spoke about the paucity of means and harsh conditions under which they made work at the time, an economy that she deemed potent. “You take an ordinary material, such as wire, and you give it a new definition,” she said. More than materials, it was the thought that made something modern. “It’s the distance between effort and effect. I’m curious to know where it will take me; it may be something very different from anything you have ever imagined.”

The show runs the gamut of the experimental practice that that attitude delineates, from the instantly recognisable sculptures in suspended looped wire to Asawa’s domestic furnishing designs and the dextrous sketches that she made daily—with clay and wire, shaved felt-tip and rhythmic dotting.

It will also expound on the DIY ethos, which was central to Asawa’s activism and arts advocacy. In 1968, she co-founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, which provided access to art to young people and children. “Art is not a series of techniques,” she liked to say, “but an approach to learning, to questioning and to sharing.”

After San Francisco, the show is set to travel to the Museum of Modern Art in New York before heading to the Guggenheim Bilbao and the Fondation Beyeler near Basel in 2026.

Grace Crowley’s Miss Gwen Ridley (1930)

Courtesy Art Gallery of South Australia

Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890-1940

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 24 May-7 September

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 11 October-1 February 2026

An exhibition celebrating 50 Australian women artists who were active in the development of European Modernism opens in Adelaide in May before travelling to Sydney in October. The title of the show, Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890-1940, was inspired by the experience of one of the artists, Thea Proctor, whose work was labelled “dangerously modern” when in 1921 she returned to Sydney after 18 years in London.

The exhibition charts the unprecedented numbers of Australian women artists who travelled to London and Europe at the turn of the 20th century to learn about Modernism at its source. Gladys Reynell and Margaret Preston sailed to Europe together in 1912, living in Paris, Brittany and London. Dorrit Black and Grace Crowley studied under the French Cubist André Lhote in Paris and both also spent time with another Cubist, Albert Gleizes, who had an artist colony in the south-east of France.

More than 200 works of art have been selected for the exhibition, including paintings, prints, sculpture and ceramics—many drawn from the collections of the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide and the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) in Sydney, which are jointly curating the show.

“Dangerously Modern brings together important works by an impressive cohort of groundbreaking women artists whose work flourished in Europe in the early 1900s and continues to captivate audiences today,” says Michael Brand, the AGNSW’s director.

Some of the artists in the exhibition have been well known since the 1980s, when feminist art historians began to study their lives and legacies. For other artists, the exhibition will mark their first institutional acknowledgement.

The painter Jenny Saville is about to have, remarkably, her first major museum show, which the National Portrait Gallery will host starting in June; among the works shown will be Drift (2020-22)

© Jenny Saville. All rights reserved, DACS 2024. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Courtesy Gagosian

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting

National Portrait Gallery, London, 20 June-7 September 2025

There cannot be many living artists who net a slot at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) for their first major UK museum show. As surprising, really, is the fact that this is Jenny Saville’s first major UK museum show. The British figurative painter has not exactly been working in the shadows for the past 30 years.

Saville emerged as part of the Young British Artists and met Larry Gagosian on the night of the famed Sensation show opening at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1997. Gagosian still represents her, while Saville was made a Royal Academician in 2007. And when her painting Propped (1992)—depicting a naked woman sitting on a black stool that looks like a bollard—went under the hammer at Sotheby’s in 2018, a telephone bidder drove the price up to £9.5m. Six years on, that is still the highest sum ever paid for a work by a living female artist.

A phone bidder drove the price of Propped up to £9.5m, still the highest sum ever paid for a work by a living female artist

From the outset, her figuration has been virtuosic, built up through expansive Baroque layering, often of multiple poses or multiple bodies, to create these bounteous forms. Saville has always sought an edge—a look, an expression, a provocative pose. Recent works have seen her eschew the looseness of earlier layerings in favour of explosive colour and more abstracted compositional elements: overlapping rectangles, each featuring a new work like so many Polaroids strewn on a table; jagged lightning lines of fluorescent pastel. Her preoccupation with what bodies do to, and with, each other, though, remains steadfast.

The exhibition will feature works from public and private collections from around the world. And big names are making further contributions, too: Roxane Gay, the author of Bad Feminist, Hunger and Difficult Women, is writing an essay for the catalogue, while the US photographer Sally Mann is contributing portraits of Saville.

Paul Feher’s Muse with Violin Screen (1930), at Cleveland Museum of Art

© Rose Iron Works Collections, LLC/Cleveland Museum of Art

Rose Iron Works: From Art Nouveau to Art Deco

Cleveland Museum of Art, 6 July-19 October

Tamara de Lempicka

de Young Museum, San Francisco, until 9 February

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 9 March-26 May

Various exhibitions

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, from 5 March

One hundred years ago, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts opened in Paris, attracting 16 million visitors over its seven-month run. The world fair is credited as the birthplace of the Art Deco movement. The distinctive style favoured simple, geometric shapes to create streamlined-looking designs that echoed the modern and increasingly mechanised era. Art Deco creations were used on everything from textiles and household objects to bridges and buildings—New York’s Chrysler Building is a shining example.

Several international art and design institutions are celebrating the centenary in 2025. The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) has the exhibition Rose Iron Works: From Art Nouveau to Art Deco, which will trace the designs of the ornamental blacksmith Martin Rose, who moved to Cleveland from Hungary during the city’s economic boom. Rose and his compatriot Paul Feher designed some of the best Art Deco ironwork in the US. The exhibition will focus on Rose’s commissions from the 1930s, including Feher’s Muse with Violin Screen (1930, left), which is in the CMA’s permanent collection.

Another US Art Deco-inspired show is Tamara de Lempicka, which presents new perspectives on the life and work of the Polish artist who synonymised the Roaring Twenties. “Her paintings, combining a classical figural style with the modern energy of the international avant-garde, have cemented Lempicka as one of Art Deco’s defining painters, with an enduring influence on today’s pop culture landscape,” a press statement says. The exhibition is on at the de Young Museum in San Francisco and will travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Over in Paris, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs is planning a whole year of celebrations. On 5 March, it will launch its new collection for drawing, wallpapers and photography, with its inaugural exhibition on designer and decorator Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann. Then Paul Poiret: Couturier, Decorator and Perfumer will explore how Poiret revolutionised fashion and liberated women from the corset. Finally, the museum will reveal new displays of its permanent Art Deco collections and open a temporary show that looks back on the 1925 exhibition that started it all.

Nicolás de Correa’s The Wedding at Cana (1696)

The Hispanic Society of America, New York

Spirit and Splendour: El Greco, Velázquez and the Hispanic Baroque

Boca Raton Museum of Art, until 30 March

Milwaukee Art Museum, 2 May-27 July

Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, 24 August-1 February 2026

As the exhibition's title at the Blanton Museum encapsulates, Spirit and Splendour reflects the unprecedented riches and distinctive religious fervour in 16th- and 17th-century Spain. The exhibition, a touring show of 57 works from the Hispanic Society of America, reflects a period in which the spoils of the conquest of America flooded Spain just at the moment in which it was an artistic centre of the Counter Reformation, the Catholic response to the Protestant surge in Europe. “Our goal is to emphasise that the artworks in the show were intended to depict the wealth of the monarchy and various patrons,” says Holly Borham, who is co-organising the Blanton's presentation of the show. “At the same time, visual splendour was also conceived as a vehicle to connect with the sacred.”

The show will include some of most important artists working in Spain at the time, such as El Greco and Diego Velázquez. But, as co-organiser and Blanton curator Rosario Granados-Salinas explains, it will also feature 14 works that were created in the Spanish Americas. “Many of these were made by travelling artists trained in Spain, but active in the so-called ‘New World’. Of those locally made in the Americas, only two paintings were made by Indigenous artists, one was made by an artist of African ancestry and three more were produced by Criollo artists [of Spanish descent].”

The texts will explain that the wealth financing these artworks was extracted from colonial enterprise

The texts around the paintings will “explain that the wealth financing these artworks was extracted from colonial enterprise,” says Granados-Salinas. “In years past, the exhibition might have been titled ‘The Spanish Golden Age’, which implies a glorification of and longing for the Spanish Empire. This was not an approach we wanted to take. We put a lot of effort into treating the art of the Americas on its own terms, not as an appendix to the narrative of Spanish art.” Borham adds: “These are beautiful objects with complex histories and we hope to present them in a way they can be appreciated and discussed critically.”

Among the highlights will be Velázquez’s delicate Portrait of a Little Girl (1638-42); El Greco’s Pietà (1574-76), where he riffs idiosyncratically on Michelangelo’s sculpture of the same name; and the shimmering The Wedding at Cana (1696) by Nicolás Correa, an example of a Mexican enconchado–a painting on wood in which mother-of-pearl fragments were inlaid into the gesso that primed the surface before the painting was made. The exhibition will travel, under different titles, having opened at the Boca Raton Museum of Art in Florida before going to the Milwaukee Art Museum and ending at the Blanton Museum in Austin.

Michaelina Wautier’s Bacchanal (before 1659) will be part of the biggest retrospective of her work yet at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, beginning on 30 September

Courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum, Picture Gallery © KHM-Museumsverband

Michaelina Wautier: Painter

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, 30 September-25 January 2026

The Baroque artist Michaelina Wautier peers out at us from the right edge of her roughly 9ft by 12ft painting, Bacchanal (before 1659), in the form of a maenad ignoring the satyr vying for her attention. This 17th-century Flemish artist faces us assuredly, for not only did she produce a monumental mythological painting at a time when women were mostly relegated to petite still lifes and portraits, but she cheekily memorialised herself within it.

For years this masterful painting languished in the storeroom of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna (KHM), where it hailed from (and was possibly commissioned by) Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, whose impressive collection helped establish the museum. Wautier was well known in her lifetime, but after her death much of her work was attributed to other artists—mostly men—which meant her legacy suffered. Though long stored and ignored, Bacchanal has been on display since 2014 and will feature in the most comprehensive exhibition devoted to Wautier to date, taking place at the museum holding the largest collection of her work. Bacchanal and Wautier are coming full circle.

Wautier was well known in her lifetime, but after her death much of her work was attributed to other artists—mostly men—which meant her legacy suffered

The show at the Kunsthistorisches, Michaelina Wautier: Painter comes on the back of growing attention in this artist. The project of resuscitating her legacy has largely been undertaken by Katlijne Van der Stighelen, an art history professor at the Belgian University of Leuven who stumbled upon Bacchanal in the KHM storerooms in 1993 while searching for a portrait attributed to Anthony van Dyck. She has since tracked down many of the 32 Wautier paintings known to date, pieced together her biography and was instrumental in organising the artist’s first retrospective at the Museum aan de Stroom in Antwerp in 2018. That exhibition was followed by Wautier’s debut show in the US, in 2022 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which focused on her series The Five Senses.

The upcoming exhibition will present some newly discovered paintings, including the public debut of Saint Joachim (c.1650), which has also long been held in the KHM collection and is the subject of both a recent crowdsourced restoration project and a scholarly catalogue presenting new archival research. The show is due to travel to the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 2026 (27 February-21 June 2026).

Indigenous works from Australia’s National Gallery of Victoria are being loaned to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, including Minyma Tjuta (Seven Sisters) (2006) by Wingu Tingima

© Wingu Tingima/Copyright Agency, Australia 2023

The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 18 October-1 March 2026

Artists from Down Under are set to make a splash in the New World when the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC, mounts The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art. The exhibition will feature some 200 works, stretching from 19th-century sketches to a 2023 video.

The show’s scale is not just impressive but unprecedented, according to E. Carmen Ramos, the NGA’s chief curatorial and conservation officer. It is “the most important exhibition of Australian Indigenous art ever [seen] in North America,” she says. After Washington, the exhibition is set to tour three more US venues—Denver Art Museum, Portland Art Museum and Peabody Essex Museum in Salem—before winding down at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

The survey is the result of an exchange between the NGA and Australia’s National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), which is noted for its holdings of Indigenous Australian art, and the sole lender to the show. In 2027, the NGA will return the favour by lending key works from its collection of American art, Ramos says.

Indigenous art from this part of the world often relied on natural pigments, explains Myles Russell-Cook, a former NGV senior curator who selected the loans. Traditional ochre and other earth tones–rendered in synthetic paint—mark 1972’s Old Man Dreaming on Death or Destiny by Mick Wallangkarri Tjakamarra, a pioneer in transferring Indigenous imagery from surfaces like caves and eucalyptus bark on to canvas. Meanwhile 2006’s Minyma Tjuta (Seven Sisters) by Wingu Tingima, a 2m-wide painting, depicts the Pleiades star cluster by using a bold palette of pinks, purples and reds.

In fact, many of the works are enormous; Anwerlarr Anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming) (1995) by Emily Kam Kngwarray is more than 8m wide. This black-and-white work, said to comprise a single whirling strand, is the artist’s “magnum opus”, says Russell-Cook. To museum-goers well versed in 20th-century Western art but unfamiliar with Australia’s Indigenous figures, the work’s fusion of dynamism and stark simplicity might look like a collaboration between Jackson Pollock and Paul Klee.

That impression is coincidental but powerful, concedes Russell-Cook. Kngwarray (1910-96) did not start painting on canvas until she was in her late seventies and “though she had little knowledge of the Western canon,” Russell-Cook says, “her work aligns beautifully and seamlessly with the principles of Modernism.” Kngwarray will also be the focus of a solo show at Tate Modern (10 July-11 January 2026).

Wes Anderson—pictured here with a variety of models from his 2018 stop-motion animation Isle of Dogs—will open his archives for a career retrospective at London’s Design Museum, beginning on 21 November, through to May 2026

© Searchlight Pictures. Photo: Charlie Gray

Wes Anderson: The Exhibition

Design Museum, London, 21 November-4 May 2026

The idiosyncratic auteur Wes Anderson is opening his personal archives for a major exhibition for the first time. In the almost 30 years since his feature film directorial debut, Bottle Rocket (1996), the American film-maker has established a unique and distinctly visual aesthetic.

For some, his meticulous, vivid colour combinations and stylised storytelling are pure whimsy; for others they inspire deep devotion, as seen, for example, in the huge success of AccidentallyWesAnderson, an Instagram account and website that has snowballed to include a book and an exhibition. Building on successful tributes to Stanley Kubrick in 2019 and Tim Burton (until 21 April 2025), the Design Museum will stage Wes Anderson: The Exhibition in collaboration with la Cinèmathèque française and Anderson’s production company American Empirical Pictures. The director himself is closely involved and has made available his archive, spanning films from Rushmore (1998) and The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) to Asteroid City (2023).

The archive is “the crux” of the exhibition, says curator Johanna Agerman Ross. “We’re starting with the archive of his things connected to films and building the story out from that,” she says. “What’s unique is that he’s retained so many props, costumes, storyboards, etc. It’s an amazing task to go through it all with his team and explore details that have been very significant for film-making history, but also understanding how important they’ve been for Anderson developing his own style and approach.”

Anderson’s inspirations are famously diverse: his love of French film, especially the absurdist excursions of the New Wave, with favourites including François Truffaut and Agnès Varda, is balanced with admiration for Martin Scorsese, Orson Welles and Agnieszka Holland. It is hard to imagine Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things (2023) without Anderson’s influence. And from Marc Jacobs to Gucci, his style has been absorbed into fashion and advertising.

The collaborative nature of film-making is often its most opaque aspect, but in Anderson’s case it is also an important detail that roots his achievement in childhood. Among his core cast of favoured actors is Owen Wilson, the school friend with whom Anderson co-wrote his first short film (an early version of Bottle Rocket) and who has been a close collaborator ever since.

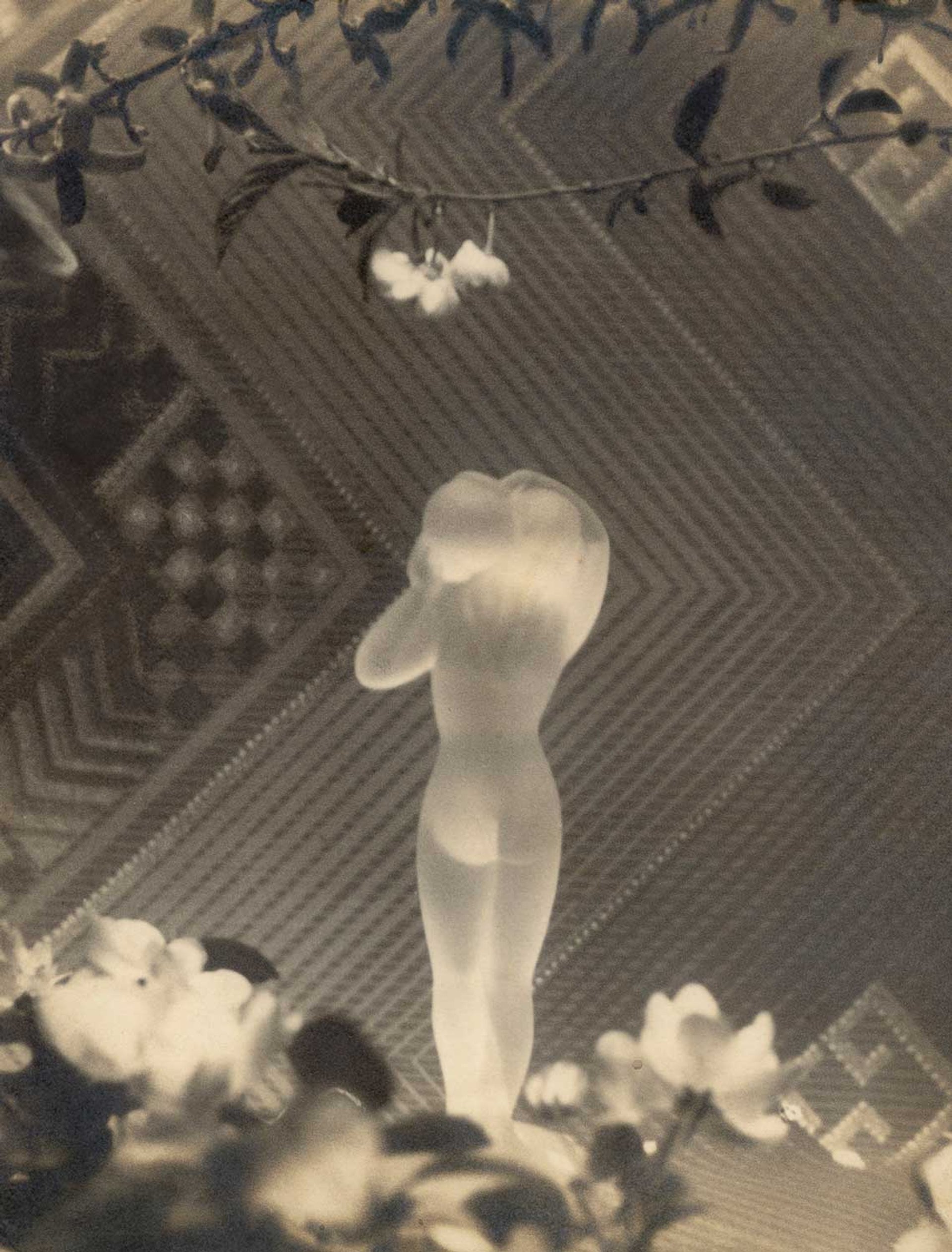

Luo Bonian’s Drawing Water from a Wellseries, from May 1932, will be shown as part of the exhibition Light and Magic: The Birth of Art Photography at Tate Modern

© Luo Bonian, Courtesy of Luo Bonian Art Foundation and Three Shadows +3 Gallery

Light and Magic: the Birth of Art Photography

Tate Modern, London, 4 December-25 May 2026

Tate Modern’s latest themed photography show aims for a revisionist history of Pictorialism, the defining movement of the medium’s development as an art form in the century that followed its invention.

Photography’s early years (the 1840s to the 1860s) were marked by startling technological innovations, but the camera was largely seen as a recording device. The Pictorialists sought to assert the new medium’s expressionistic qualities, preferring painterly composition, atmospheric soft focus and rich tonality.

But there was much more to it than that, says Charmaine Toh, the Tate’s curator of photography. Toh says that she wants to “move away from thinking of Pictorialism as a style, which results in many blind spots. Instead, we should think about it as a movement that was rooted in a desire to position photography as fine art, and which created the structures for that to happen, particularly with exhibitions, salons and clubs.”

The Pictorialists sought to assert the new medium’s expressionistic qualities, preferring painterly composition, atmospheric soft focus and rich tonality

Its proponents were evangelistic and their network spread far and wide, creating deep ties beyond the current Eurocentric narrative that focuses on the movement’s supposed heyday of the 1880s up to the First World War, led by The Linked Ring in England, the Photo-Club de Paris in France and the Photo-Secession in the US.

While leading figures such as Henry Peach Robinson, Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and Alvin Langdon Coburn will be represented in the exhibition, so too will less familiar names such as Luo Bonian and Long Chin-san, Shapoor N. Bhedwar, Wu Peng Seng, Han Youngsoo, Ho Fan—“and even British photographers who have been largely forgotten, like Emma Barton and Eveleen Myers,” Toh says.