Since Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Kharkiv—the second largest Ukrainian city and a cultural hub—has been under daily fire. During this time, bombs have exploded within feet of the city’s Yermilov Centre for contemporary art, which operates both as an official bomb shelter and art space.

Over the autumn, Yermilov Centre marked the 1,000th day since the invasion (19 November) and its approaching third anniversary with an international exhibition and ongoing project, Sense of Safety.

Sense of Safety examined, with uncanny timing, the “ambivalence of the concept of safety, which has been profoundly redefined by the war”, and the need for “bridges of solidarity”.

Among the exhibits was the installation Bed, Carpet, Brooch by the Kharkiv-based artist Pavlo Makov, which draws on his experience of Yermilov Centre as a bomb shelter. Makov, who was Ukraine’s representative at the 2022 Venice Biennale, has remained in Kharkiv despite the continuing bombardment. The Belgian artist Francis Alÿs and the Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn are also participating in the show and travelled to Kharkiv: Alÿs in 2023 to film a video that was shown at the exhibition; Hirschhorn during its run to host a series of workshops called Energy = Yes! Quality = No!.

Installation view of Pavlo Makov, Bed, Carpet, Brooch (2024)

© YermilovCentre. Photo: Viktoriia Yakymenko

Nataliia Ivanova, Yermilov Centre’s founding director, emphasised to The Art Newspaper that the exhibition was addressing global concerns. “The question of feeling safe in the world is a general question for everyone,” she said on Zoom from Kharkiv, after a gruelling multi-leg journey home from a conference in Amsterdam about Ukrainian wartime artist residencies.

“While there are dictators in the world, no one can feel safe,” she said as anti-government protestors faced off with Georgia’s pro-Russian government in Tbilisi and Syrian rebels toppled dictator Bashar Assad, who fled to Russia. This sense of safety extends to “other tragic things that can happen [to] people”, she says, such as the international climate and food crises.

Looking further afield

Parallel Sense of Safety events at venues across the European Union, Ukraine and Georgia included two Ukrainian photography exhibitions in Tbilisi organised by Bouillon Group, an activist collective based in the Georgian capital. The group has operated in the Georgian art scene for 18 years and are known for their political performances, often held in public space.

Tbilisi has been gripped by anti-government demonstrations against the ruling, pro-Russian Georgian Dream party. These began in the aftermath of the parliamentary elections, which demonstrators claim were rigged—a suggestion Georgia’s prime minister Irakli Kobakhidze denied—and have continued over the party’s decision to suspend European Union (EU) membership talks. Parallels have been drawn to the Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan Revolution, which broke out after plans to sign an association agreement with the EU were quashed.

The protests in Georgia have been met what the EU has condemned as “brutal, unlawful force from the police” and targeting by “informal violent groups”. Amnesty International states that more than 460 people have been detained to date, with “reports indicating” that around 300 have been subjected to torture and other ill-treatment. On Saturday, Mikheil Kavelashvili, a pro-Russia critic of the West, was elected president, replacing the pro-EU Salome Zourabichvili.

Bouillon group told The Art Newspaper in a statement: “We saw how the Georgian Dream stole from us the last chance to change the situation with democratic elections.” The group compared the situation in their country to Belarus’ contested 2019 elections, during which cultural figures rallied against the dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka [often spelt Lukashenko] and were subject to a brutal crackdown.

Sense of Safety was created in collaboration with antiwarcoalition.art, an online project formed by Belarusian cultural workers that collects and shares statements against war from artists around the world.

“A part of [our team] is cultural workers from Belarus, so we constantly focus on the [country’s] dual position in the ‘big’ war,” said Antonina Stebur, an exiled Belarusian curator working on the exhibition. “Belarus, on the one hand, provides its territories for Russian troops and weapons. On the other hand, even now anti-war actions continue inside the country, despite constant detentions, unprecedented terms, and a huge number of political prisoners.”

Tatiana Kochubinska, a Ukrainian member of antiwarcoalition.art, says it was essential for Sense of Safety to be held in Kharkiv, which is just 30km from the Ukraine-Russia border. Ivanova, she continues, was “constantly arguing how important it was to create an exhibition and bring art to the city [while] at war,” while co-curator Maryna Konieva “developed the concept of the whole project being present in the city at the most difficult times of shelling, bombardments and blackouts, volunteering and evacuating art collections.” Kochubinska adds that Taras Kamennoy, a participating Ukrainian artist, conveyed that “the exhibition has given him a feeling that he is alive again.”

The fact that Alÿs and Hirschhorn were marquee participants in the show is perhaps notable, given that in 2014, shortly after Russia illegally annexed Crimea from Ukraine, they both created installations for the roaming biennale, Manifesta 10, which was held at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. Some artists, including the art collective Chto Delat, chose to boycott the edition, Chto Delat citing “the Russian government’s policy of violence, repressions, and lies”. Others used the exhibition to challenge the government, including on its recently introduced laws restricting LGBTQ rights.

Installation view of Francis Alÿs, Children’s Game #39: Parol (2023); with Iryna Loskots Camouflage (2024) in the foreground

© YermilovCentr. Photo: Viktoriia Yakymenko

Yet both Alÿs and Hirschhorn have showed genuine solidarity with Ukraine. “Both Francis Alÿs and Thomas Hirschhorn shared experiences with people in Kharkiv and the Kharkiv region, and experienced the same risks,” says Kochubinska. A sense of connection was made clear in their work for Sense of Security: Alys’s film Parol was created in Kharkiv in 2023, while Hirschhorn’s workshops resonated, an exhibition statement reads, with Kharkiv and “particularly Yermilov Centre, [as] a gathering place and focal point that generates unique energy, which today might help resist terror and fuel hope”. Hirschhorn also expressed his solidarity in a heartfelt Instagram post.

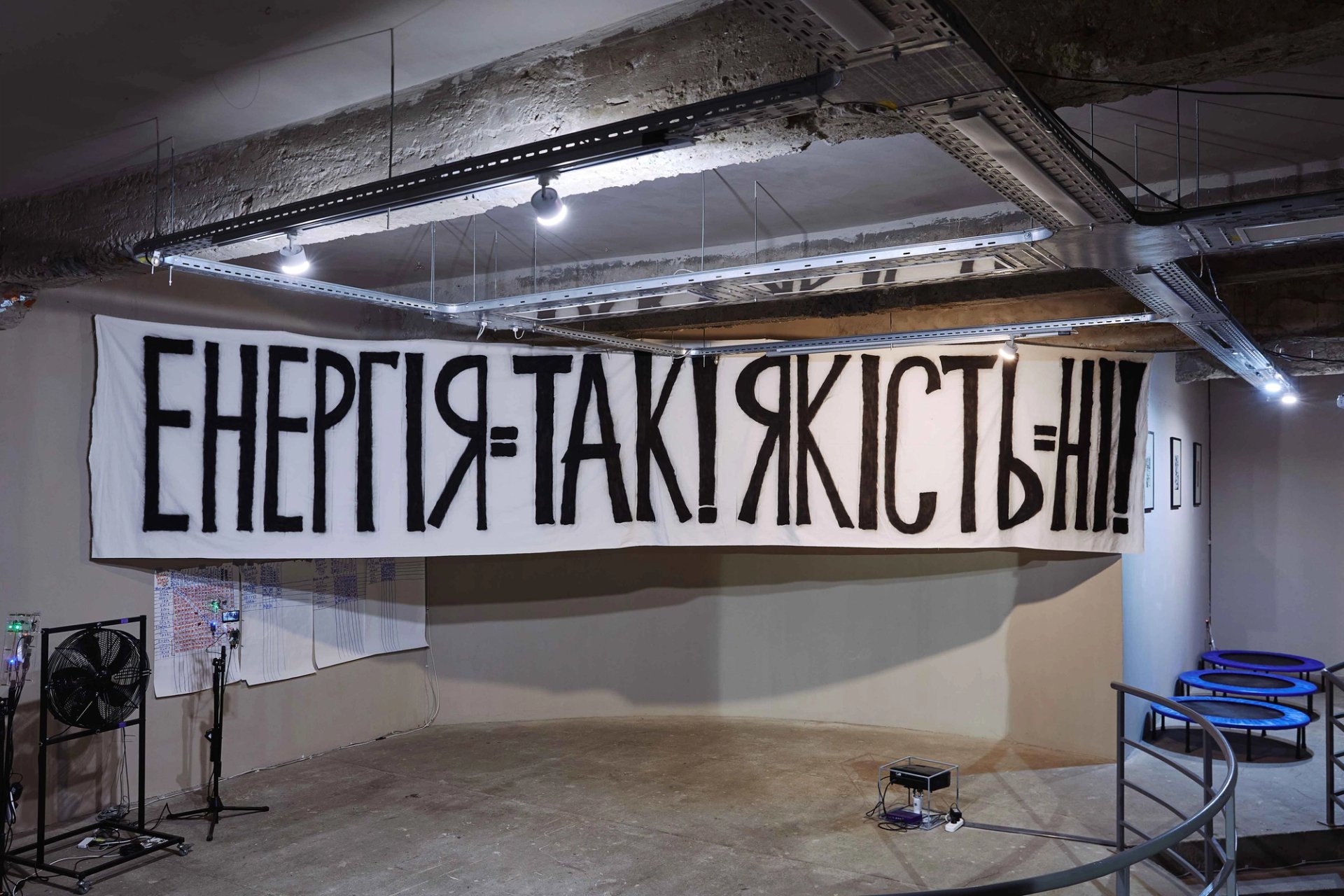

Installation view of Thomas Hirschhorn, Energy=Yes! Quality=No! (2024), a banner marking the culmination of the artist’s series of workshops; and Yulia Kostereva & Yuriy Kruchak All That’s Solid Melts into Air (2024)

© YermilovCentre. Photo: Viktoriia Yakymenko

There is a broader anti-colonial impulse at the heart of Sense of Safety too, Stebur pointing to the Kurdish artist Ahmet Öğüt’s work as an example. He has replicated works by Ukrainian artists from different generations—including Alla Horska, who was brutally murdered in 1970—to highlight ”the intertwined political and artistic legacies of these individual,” says Stebur. By focusing on these artists he also seeks to rethink “the history of art, overcoming Western European centrality,” according to an artist statement.

A national effort

Also created in the run up to the third anniversary of Russia’s invasion is Ribbon, a platform dedicated to supporting Ukrainian cultural heritage and contemporary art. Last month, Ribbon opened the Ukrainian debut of Zhanna Kadyrova’s installation Instrumnt, comprising a playable organ infused with Russian missile shells that the artist gathered in Kyiv.

A musician playing Zhanna Kadyrova’s installation Instrument

Photo: Ukraine Railways

The work, first shown at this year’s Venice Biennale, was unveiled on 22 November at Lviv railway station. Ukrainian Railways, or Ukrzaliznytsya, have been a lifeline in the war, transporting troops to the frontline and civilians to safety. Kadyrova has organised a series of concerts involving the organ that will run until 19 January 2025.

After witnessing the reaction to the work, she is imagining it as a form of physical and psychological rehabilitation for war veterans. Art, Kadyrova adds, is also a way to for overcome Russian propaganda and “bring information to people who are tired [after] 1,000 days of war”.

Kadyrova’s actions to address the impact of the war have been various. She sold works from her 2022 project Palianytsia (bread in Ukrainian)—organised as part of a residency sponsored by the gallery Asortymentna Kimnata, in Ivano-Frankivsk—to raise money for equipment for troops on the frontline immediately after the invasion. (The word “palianytsia” became a form of codeword, to help identify Russian soldiers, when the invasion began because Russians often mis-pronounced it; Francis Alÿs’ video for Sense of Safety, an installment of his Children’s Games series, focuses on this use.)

A visitor at Contemplating the Empathy of Others at Stadtgalerie Künstlerhaus Lauenburg

Courtesy of Assortymenta Kimnita

Also produced as part of the Asortymentna Kimnata residency is Red Horse, a photo collage project by artist Sasha Kurmaz that—through images of writings, found objects, destroyed infrastructure and more—shows how life in Ukraine is being transformed by the war. An exhibition focused on the work opened on 23 November (until 9 February 2025) at Stadtgalerie Künstlerhaus Lauenburg, Germany.

“We were trying to play a little bit with the classic work of [the critic and theorist] Susan Sontag [on the topic of] watching and contemplating the pain of others,” says Alona Karavai, the founder of Asortymentna Kimnata, of the exhibition.

She adds that she wanted to query “what happens with empathy when there are too many pictures of this war—or when it’s going on for longer and getting even more cruel, but people are getting used to the level of cruelty.”