A rare version of a famous bronze by Camille Claudel, lost for more than a century, is coming to auction after being discovered in an abandoned Paris flat.

Certified by the French sculpture experts Cabinet Lacroix-Jeannest, it will be offere through the Orléans auction house Philocale on 16 February at an estimate of €1.5m to €2m.

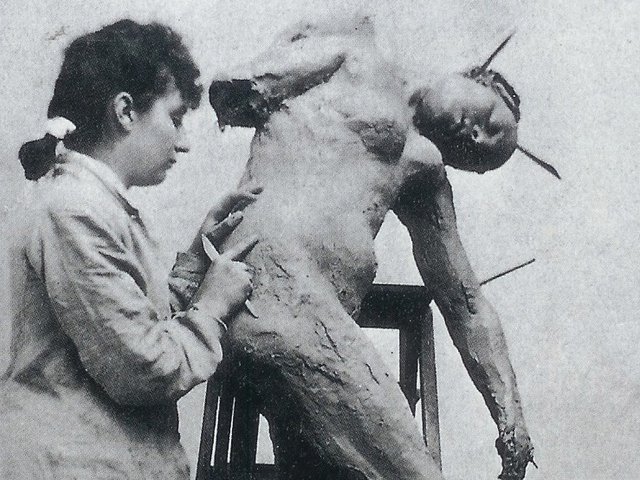

Known as La Jeunesse et L’Age Mûr, or simply L’Age Mûr, the nude group depicts a man and two women, one old and haggard drawing him forward, the other young, kneeling behind him, begging him to turn back. Executed in Claudel’s characteristically powerful expressionist style it lends itself to multiple interpretations: an allegory of life’s trajectory but also of Claudel’s personal tragedy. Conceived during her break-up with her teacher and lover Auguste Rodin, which led to her emotional collapse and psychiatric internment, the autobiographical roots are visible. The kneeling girl has Claudel’s features and the male figure reference’s Rodin’s Burghers of Calais, says Alexandre Lacroix, a Claudel specialist who suggests that the older woman may represent Claudel’s nemesis Rose Beuret, Rodin’s housekeeper and later his wife.

The bronze was found in an abandoned Parisian flat

Courtesy of Philocale

Only three other bronzes of the whole work are known. The Musée Camille Claudel in Nogent-sur-Seine has one from same mould. Two larger casts are in the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée Rodin. Independent versions of the kneeling girl also exist.

Claudel first proposed a maquette of the group to the Paris Salon in 1895. The French state commissioned a plaster version which has since disappeared. A private commission for a lost-wax casting in 1902 produced the larger format bronze in the Musée d’Orsay. A second casting in 1913, the year of Claudel’s internment, produced the one now held by the Rodin collection.

The newly found work is number one of a limited edition of six, sand-cast at one-third scale by the foundry owner and art dealer Eugène Blot in 1907. The Claudel Museum’s is number three. Lacroix says the others may have been melted for metal during the German occupation of France.

The bronze was discovered by Philocale’s auctioneer and valuer Matthieu Semont while preparing an inventory for the inheritor of the apartment, but how it came to be there is a mystery. But the gap in provenance is unsurprising, Lacroix says, noting that Claudel’s re-emergence from obscurity has been relatively recent. When women artists were little valued and mental health issues were an embarrassment, Camille Claudel ticked all the wrong boxes.