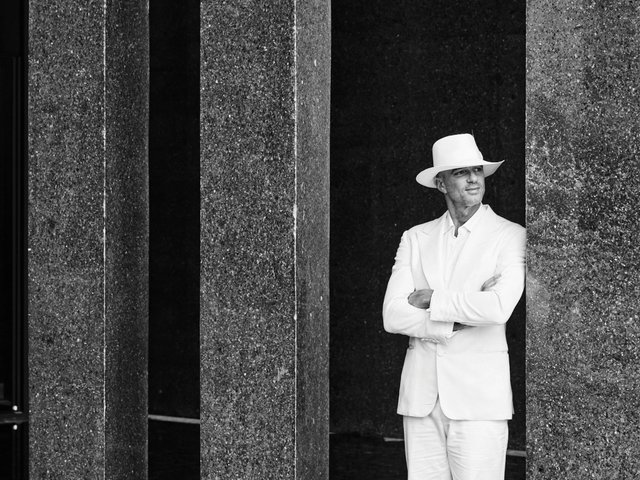

Craig Robins, for two decades one of the main players and tastemakers in the Miami art scene, is a champion of the power of creativity—music, architecture, museums, art and arts education—to build places where people are attracted to live and work.

The Miami-based art lover and real estate developer has been a central figure in the partnerships behind the revival of South Beach—working with the record producer Chris Blackwell, in the late 1980s and 90s, to revive the area’s decaying Art Deco hotels and make them the heart of a new hub for music and fashion—and the reinvention since the early 2000s of the once down-at-heel furniture district, six miles to the west, as the Miami Design District, a high-end retail centre rich in music, art institutions and public art.

These urban renewal initiatives and his love of art meant Robins was well placed to engage with Art Basel about bringing their art fair brand to Miami Beach, in 2002, before helping to launch Design Miami—which has become the pre-eminent fair for collectible design with editions in Miami Beach, Basel and Paris—in 2005. (Last year, Design Miami was acquired by basic.space, an ecommerce platform in which Robins is an investor.)

The inspiration of John Baldessari

In 2024, Robins has been as active as ever as a collector, patron of public art and supporter of art institutions across Miami. This year’s exhibition from his collection—part of an annual rotation of around one-fifth of its 1,500-plus works on show at the Design District offices of Robins’s property company, Dacra—demonstrates his considered approach to buying the work of young artists, where he aims to continue to collect them in depth while studying both contemporary and historic influences on their practice.

It is an approach, Robins tells The Art Newspaper, which he largely credits to his 37-year friendship with the conceptual art pioneer John Baldessari, who was known for developing modes of expression—at the meeting point of text, paint and photography—that were at once novel but connected to the past.

Titled The Sleep of Reason, the exhibition includes recent acquisitions by millennial artists including Bony Ramirez (born 1996), Mario Ayala (1991), Alteronce Gumby (1985) and Jill Mulleady (1980). The work of Jana Euler (born 1982) is being shown in depth (12 canvases) with that of Kai Althoff (20 canvases). They are two artists, the collection’s website states, “whose drawings, paintings and sculptures engage with abject imagery, often presenting delirious or complex emotional landscapes in their figuration”—in line with the nightmare visions of Francisco Goya’s celebrated aquatint The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters from his etching series Los Caprichos (1797-99).

Robins, who learnt his love of art from communing with Goya’s masterworks in the Museo del Prado while studying Spanish in Madrid as a teenager, developed his art-historical collecting template—looking to the future while relating to the past—in the early 1990s. Then still in his late twenties, he acquired the work of younger artists, including Mike Kelley and David Salle, before a transformative meeting in 1993—arranged by the visionary curator Bonnie Clearwater—with Baldessari, who had taught both Kelley and Salle. Robins bought three works by Baldessari, including his celebrated text piece Clement Greenberg (1966-68). As the two men became close friends, with a shared fascination for the work of Goya and Marcel Duchamp, Robins continued to collect works by the witty, inimitable, father figure of the Los Angeles art scene.

“My goal wasn't to buy one of each, but actually to watch their careers unfold,” Robins tells The Art Newspaper of his early foray into collecting Californian artists. Once he realised that Baldessari was their shared teacher, “there was a very natural connection into what I was doing”, Robins says, “and I bought three masterpieces by him. That was by far the most ambitious purchase I had made. We immediately became good friends and I continued to collect him throughout his life, so I now have 45 works from the 1960s to the end of John's life that reflect his incredible talent. And because I was collecting John, as one thing leads to another, I naturally had to buy a work by Duchamp. So I own Marcel Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages [1913-14].”

Clement Greenberg was one of the anchor loans of more than 40 works that Robins made to John Baldessari: The End of The Line, a survey of the artist’s work—overseen by Karen Grimson, curator of the Craig Robins Collection—that ran for four months from July this year at the Museum of Latin American Art (Malba) in Buenos Aires. It was the first museum show of Baldessari’s work since his death nearly five years ago, in January 2020. “Wonderful people came,” Robins says, “and some of the artists that John was really close to, and I knew through John, also joined. […] It felt like John was there almost, which obviously he was not, but his spirit might have been.”

Public art in Miami

Baldessari’s work and friendship is threaded through Robins’s role in the transformation of Miami into a global art centre. Writing in the catalogue for the Malba exhibition, Robins recalls with “particular clarity” the experiences he shared with Baldessari at Art Basel Miami Beach. The artist’s presence is palpable today in the Miami Design District with two giant murals commissioned by Robins for the City View Garage building completed in 2014. Fun (Part 1) shows a very Miami scene of people enjoying games around a swimming pool. It was integrated by Baldessari, Robins says, into the architecture, where it is placed on “almost ventilated screening” of the parking garage. On the north wall is Fun (Part 2), another monumental image, this time on vinyl, a beach scene in which a woman attempts to balance on a ball. Both the Fun works demonstrate Baldessari’s quest for simplicity in art. They were, Robins says, two of the artist’s favourite images.

“Public art to me is a very important thing,” Robins says, “and especially site-specific public art. You’re getting away from this idea of the object and thinking past it [to] the integration of art into architecture, into urban design. And John did a masterful job.”

Robins and Dacra’s partners at L Catterton Real Estate came up with the public art focus for the Design District—what Robins calls an “outdoor museum of art, architecture and design”— after bringing in DPZ CoDesign, led by Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, to produce a community-based urban design. They devised a north-south path through the district with plazas and shade trees against the Florida sun to make it walkable. Public art was integrated as a form of wayfinding—defined by DPZ as “murals + fountains + sculptures = oriented, challenged & delighted visitors”. One of the most striking pieces in the district, Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec’s Nuage (2017), an “organic pergola”, acts as a shading sculpture, as does Urs Fischer’s Bus Stop (2017), a fountain set in a re-creation of a Miami Beach bus shelter.

A pedestrian passageway in the Miami Design District Courtesy Miami Design District

It was especially nice, Robins says, to work with Baldessari on the Fun project, because in 1994 the artist had made a mural design for the building in South Beach that was then home to Dacra’s offices, but the project was not implemented. (Baldessari’s playful, collaged proposal, mixing a giant orange with a line of Miami pedestrians of mixed ages with the backdrop of strips of Floridan beach and the deep-blue Atlantic, featured in the Malba show.) So being able to realise a mural with Baldessari in 2014, Robins says, “in a much larger, more important project in the Design District was really wonderful”. Robins says he has been talking this year to the Baldessari estate about the possibility of setting up a temporary installation that would recreate the 1994 South Beach building as a mural in the Design District. “We’ll see if that happens,” he adds.

Public art in Miami’s Design District

There are two Baldessari works in The Sleep of Reason, and two featured millennial creators, the British fashion designer and artist Samuel Ross and the Pennsylvania-born, New York-based artist and film-maker Alteronce Gumby, also have public art commissions on show in the Design District. Ross is represented in the Dacra exhibition by three of his furniture pieces: Trauma Chair (2020), Amnesia or platelet apparition? (2021) and Optimistic uncertainties solicit integration (2023).

“For several years I had been collecting Samuel [Ross]’s works, his furniture pieces,” Robins says. “We always try to do things in a special way in the neighbourhood. We needed to do new benches and thought, ‘Who would be the most incredible person to come and make these special benches?’” Ross accepted the commission for the Design District benches, which he executed in his distinctive, elegantly arched organic manner.

The exhibition also includes Gumby’s Soft Stars and Hard Thunder (2024), a 6ft by 6ft panel of gemstones and glass with acrylic. Gumby’s trademark use of gemstones also features in his first public art piece for the Design District, which was unveiled on 2 December.

Craig Robins (left) and Alteronce Gumby (right) cutting the ribbon on the latter's new mural in the Miami Design District Photo courtesy Miami Design District

“We’ve always been focused on making creative neighbourhoods and integrating culture to help create a sense of place,” Robins says. “The Design District is the ultimate expression that I have been involved with that I believe achieves that. It’s an outdoor museum of art, architecture and design. It’s got lots of content between music and art, whether it’s the Institute of Contemporary Art, our collection, the concert series that we do with [the musician and producer] Emilio Estefan, Miami Symphony Orchestra, as some examples. It’s an outdoor museum of architecture and design, every 50 feet, whether you’re looking at Buckminster Fuller's beautiful Fly’s Eye Dome, or walking down the street and seeing works by John Baldessari and Urs Fischer.”

“It also inspires people that are opening businesses there to think differently,” Robins adds. “It demonstrates the importance of creativity and how consciously and unconsciously it impacts people’s brains.”

Asked about the challenge (both locally and internationally) of finding backing for the arts in education, Robins says he finds it “unfortunate, for example, in public schools, how little interaction kids have with art. It’s disregarded” and creative disciplines are not given equal priority to maths and science. “But in fairness, there’s a large part of the public that doesn’t understand the value of this and to some extent it’s because the value is unconscious; if you connect to art, or you connect to music, you feel better. It helps enlighten you and give you a sense of quality of life. But a large part of what’s happening neurologically in your brain, you’re unaware of it.”

“The success of the Design District,” he says, is down to “the creative component”. If political leaders were to understand that better, Robins says, “I think that our communities and society would grow in a positive way. It’s not really to me about politics, it’s about understanding. I don't believe that any leader, if they knew the value of [education in the arts], would say, ‘No, we're not doing it.’”

“Effective enthusiasm” for the arts

Robins is an effective enthusiast for the arts who delights in the moments when things turn out even better than hoped. “When you have a vision and the experience is much more than the vision, that’s what excites me more than anything,” he says. Asked about a memorable art experience in the past 12 months, he recalls being taken by surprise this summer at an exhibition by the German artist Jana Euler—one of the featured artists in this year’s Dacra show—at Wiels, in Brussels. He delighted in the way that Euler’s installation played with optical illusion, cutting a path through its own walls—in what Euler describes as “a box within a box”.

“I walked into the show and as you walk in, you see this painting of a camera. But I’m sitting and staring at the painting and I’m so confused because I feel like I’m looking at a mirror,” Robins recounts. “But I’m actually looking at a painting. It’s not a reflection of me. And of course, it’s a camera. What does a camera do? It does what a mirror does. It takes a picture of you. I’m totally confused. And then I realised that Jana had cut out from the wall that I was looking at—an open space—and that the painting was 20 feet back. It was creating an optical illusion that was so brilliant.

“And then we walked into the space and there was a reproduction of a building, but in the corner. You’d see the building, but rather than it looking like it was in the corner, the architecture was coming out. Again, this very confusing optical thing, because you know you’re looking at a corner and how is it coming out at you? And she even cut out sections of the wall so you could stand far away and see all the way through to this building she’d put in the corner. That was something that has inspired me recently in art.”

Robins’s enthusiasms for the transformation of South Beach remains undimmed. “I had these visions about it, and I clearly saw it, but then when it was happening and I was living in it,” he recalls. “When Chris Blackwell and I opened the Marlin Hotel and U2 flew in for the opening of a 12-room hotel, I said, ‘Well, this is a lot better than I ever imagined it could be.’”