“I have taken a lot of solace in my characters,” the film-maker Tim Burton writes in Designing Worlds: “the feeling of everything being quite odd and strange when you’re coming to terms with life as a child.” Drawing on Burton’s personal archive, the book traces how he has brought an outsized gothic sensibility to contemporary cinema and art, using a distinct visual language that blends melancholy, horror, fantasy and macabre mythology, informed by gothic literature, Modernist and Futurist art, classic horror, German Expressionist cinema and pulp sci-fi.

Maria McLintock, the editor of the lavishly illustrated Designing Worlds and curator of the corresponding exhibition at the Design Museum, London (until 21 April 2025), goes beyond the early films for which Burton is best known—Beetlejuice (1988), Batman (1989) and Edward Scissorhands (1990)—to show Burton’s range as illustrator, painter, photographer and author, while placing his interest in the gothic in a social-political context.

Burton was born in 1958 in the quietly affluent Los Angeles County suburb of Burbank (in the shadow of the Hollywood sign) and was raised in a white-picket-fence family that conformed to the American Dream; his father was a retired minor league baseball player who worked as a senior civil servant, his mother ran a cat-themed gift shop. Fans of Edward Scissorhands and Beetlejuice will recognise the conformist middle-class milieu, one from which Burton’s most memorable protagonists struggle to escape.

Teenage talent

The teenage Tim showed talent: winning an anti-littering poster competition and spending hours alone in his bedroom or the backyard, making crude animations. His first credited film, The Island of Doctor Agor (1971), adapted from an H.G. Wells novel, featured footage of caged creatures shot surreptitiously in Los Angeles’s zoo. In an interview with McLintock, Burton recounts how art became for him a self-imposed therapy: “Growing up, I was very much an introvert: I didn’t feel very communicative, so drawing became my means of expressing thoughts and feelings I struggled to articulate verbally.”

While at the California Institute of the Arts he developed an interest in illustration and stop-motion animation, before working for Disney—he submitted an illustrated children’s book in lieu of a CV, pages of which are joyously reproduced in Designing Worlds. But Burton was not a company man. The animation tasks assigned to him did not marry with his own subversive vision, on which he was unwilling to compromise, and his superiors reassigned him to work on The Black Cauldron (1985), a fantasy adventure film set in the Early Middle Ages and based on Welsh mythology. Burton’s illustrations did not make the final cut.

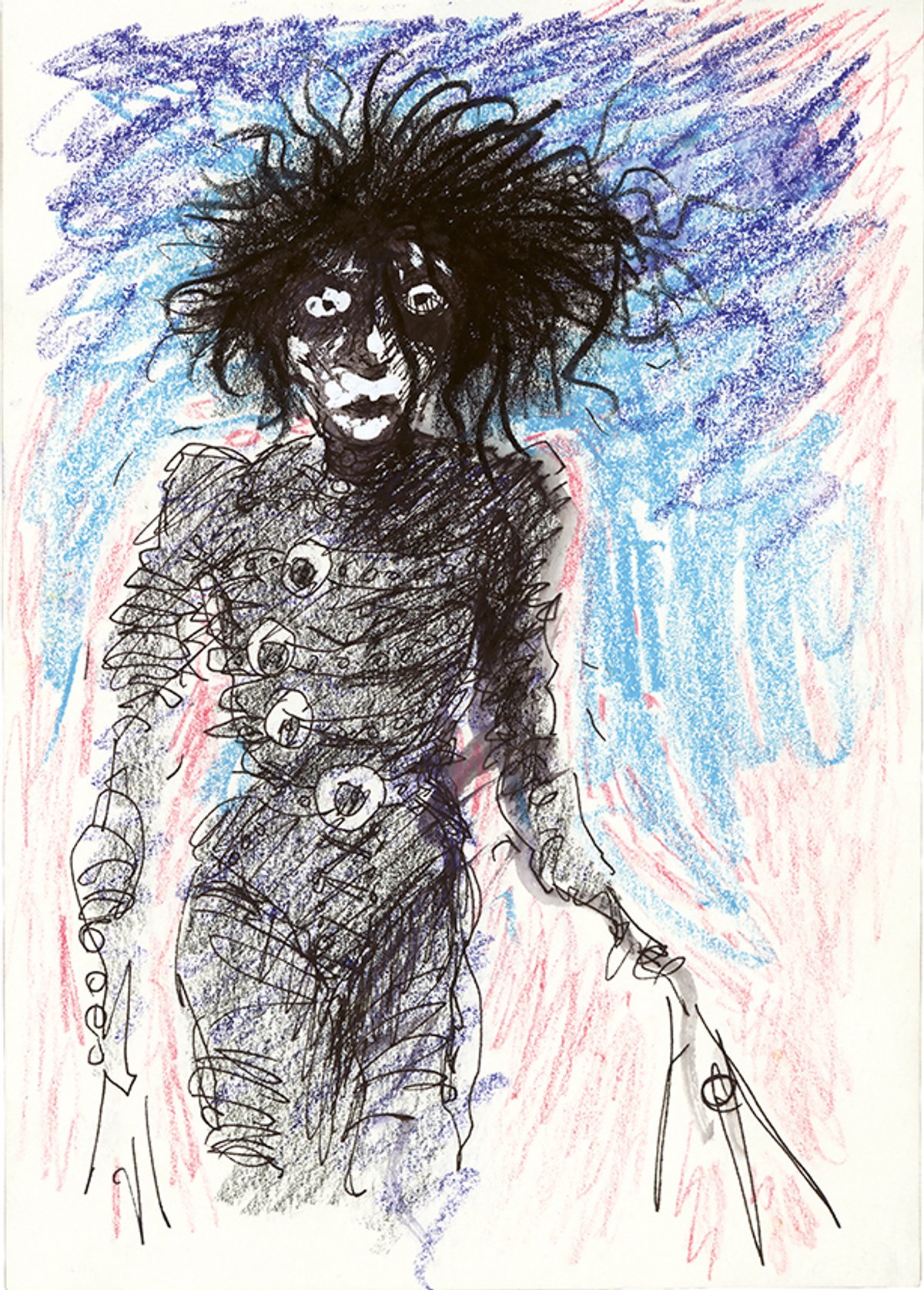

Designing Worlds focuses on the ingenuity of the set design and intricate storyboarding of the early films, an imperfect but creatively audacious and impressionistic approach to world-making, that has influenced many artists working in his wake. In Beetlejuice, Burton created a world that oscillated between mundane suburban settings and a chaotic afterlife built on warped shapes, nauseating colours and exaggerated structures. Created on a tiny budget, and seemingly held together with sticking tape, the world of Beetlejuice builds on the legacy of foundational Hollywood fantasy films such as The Wizard of Oz, in which reality and the supernatural coexist uneasily, while embodying what Burton calls his “gothic surrealism”. In Edward Scissorhands, Burton’s set design likewise juxtaposes the sterile, pastel-coloured suburban world with the gothic, decaying mansion where Edward lives.

Burton’s latter career has included some notable turkeys: Alice in Wonderland (2010) shot in short-lived 3D, is widely regarded as one of the ugliest movies ever made. Burton works best when the seams are sagging and visible, and the set might collapse at any moment. The sheen of computer-generated imagery has never suited him. Designing Worlds might have been more willing to engage critically with this bloated later period.

But Burton’s influence is clear, extending far beyond film. A range of creatives—from rock stars to children’s illustrators to fashion designers like Hedi Slimane and Issey Miyake—have drawn on Burton’s aesthetics, incorporating his sensibilities and using his characters and themes as direct inspiration. Designing Worlds pays homage to the way Burton’s work has reshaped cultural perceptions of darkness, melancholy and death, while championing the gothic not as a relic of the Victorian era, but as a living, breathing aesthetic that informs and engages with contemporary societal concerns.

• Maria McLintock (ed.), Tim Burton: Designing Worlds, Design Museum Publishing, 272pp, colour illustrations throughout, £29.95 (at the Design Museum exhibition)/£34.95 (pb), published 14 November

• Tom Seymour is a freelance writer and the former museums editor of The Art Newspaper