A marvel of medieval construction that helped pioneer the ribbed vault and the flying buttress, Notre-Dame reached something like its recognisable form in 1270, just shy of a century after construction started. After getting a Baroque makeover in the 18th century, and becoming a wine warehouse following the French Revolution, it was revived in the mid-19th century, when its vertiginous spire and decorative rooftop chimera were first added. Along the way, artists have been there to document, depict, and delight in its development, with our own era’s smartphone owners joining their ranks to witness its 2019 near-fatal fire and its rapid reconstruction.

Eugène Delacroix, 28 July 1830, Liberty Leading the People (1830) Courtesy of Musée du Louvre

Eugène Delacroix

28 July 1830, Liberty Leading the People (1830)

Musée du Louvre, Paris

In July 1830, Charles X got the sack when Parisian mobs turned a series of spontaneous skirmishes into a rapid revolution. In a massive allegorical painting, Delacroix commemorated the event in this scene (above) on the barricades, with a resolute and otherworldly Liberty leading Parisians into battle. And we know it is Paris, because the towers of Notre-Dame are clearly visible in the mire, in the painting’s upper right.

In the chaos of that summer, the cathedral got a catastrophic blow when rioters, renewing the secular passions of revolutionaries a generation before, broke stained-glass windows and set fire to a nearby building.

Henri Matisse, View of Notre-Dame (1914) © 2024 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of MoMA

Henri Matisse

View of Notre-Dame (1914)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

During his Paris phase, the great master of 20th-century art Henri Matisse had a studio on an upper floor at 19 Quai Saint-Michel, overlooking Notre-Dame. He painted the cathedral many times, including this figureless, near-abstract depiction, which reduces its west façade to a shadowy black block.

Matisse’s visits to Morocco in 1912 and 1913 had impacted his palette, and the painting, completed a matter of months before the outbreak of the First World War, reflects that change.

After building up the canvas over time, Matisse eventually covered it in a rich but scratchy blue, which seems to subsume the scene in earthbound sky.

Jean Fouquet, The Right Hand of God Protecting the Faithful Against the Demons (around 1452-60) Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

Jean Fouquet

The Right Hand of God Protecting the Faithful Against the Demons (around 1452-60)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

French art reached an early flowering thanks to Jean Fouquet, the Renaissance painter who fused Italian and Netherlandish influences. In a tempera-and-gold-leaf miniature included in Hours of Étienne Chevalier, an illuminated prayer book commissioned by the treasurer to King Charles VII, Fouquet depicts Medieval Paris a few centuries after Notre-Dame’s initial completion. In a scene marked by topographical accuracy and religious reverie, he has the cathedral’s west façade presiding over an evening prayer, while fantastical demons flee from the supreme and sublime hand of God.

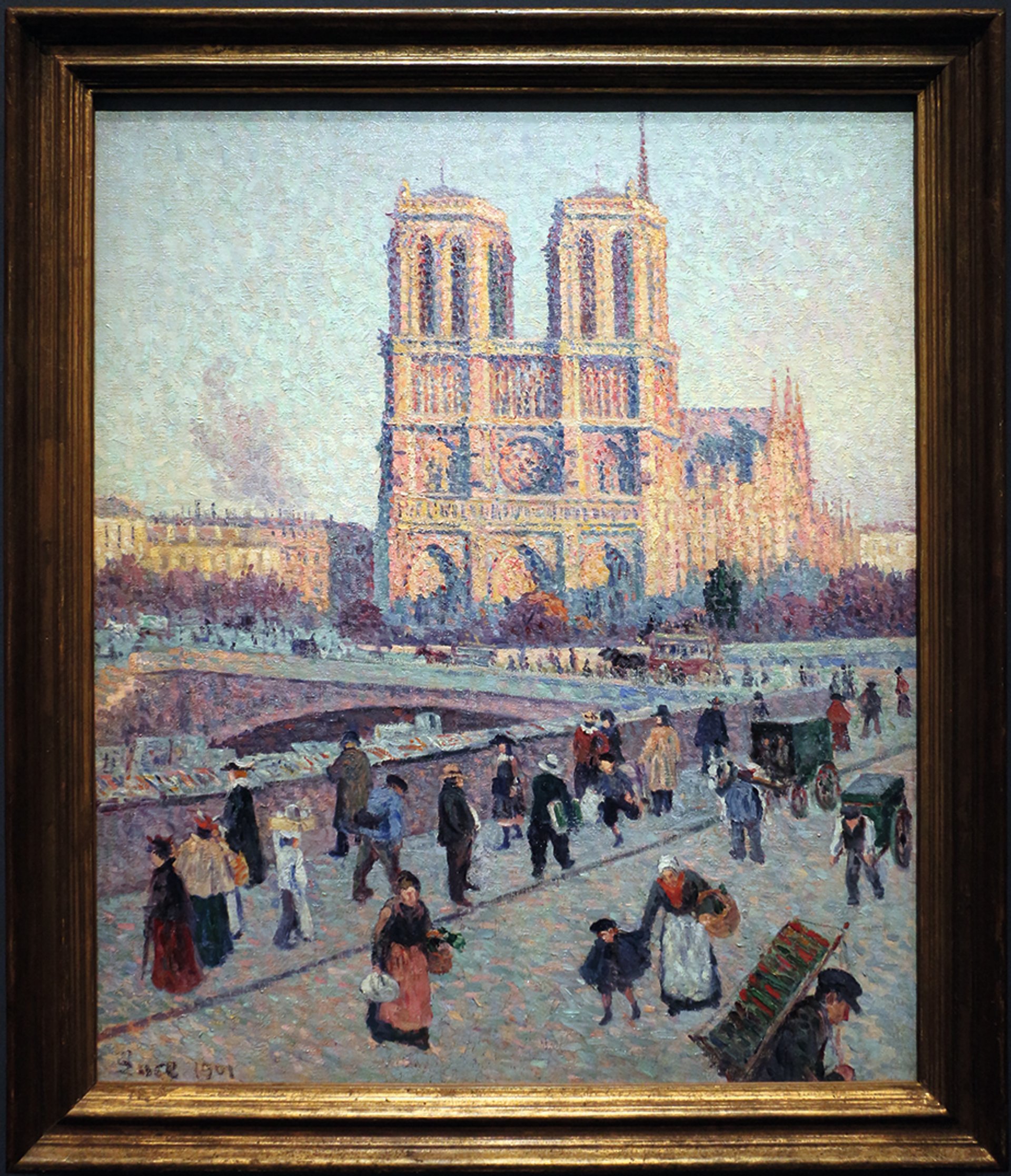

Maximilien Luce, Le Quai Saint-Michel et Notre-Dame (1901) Courtesyof Musée d’Orsay

Maximilien Luce

Le Quai Saint-Michel et Notre-Dame (1901)

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The neo-Impressionist Maximilien Luce bid adieu to Seurat-style Divisionism in his series of paintings of Notre-Dame, including this Left Bank view, which showers the cathedral’s west façade in a cascade of orange, pink, red and blue. The rich urban scene below is both static and dynamic, with figures frozen in motion while scampering in every direction.

Now part of the Musée d’Orsay’s permanent collection, Le Quai Saint-Michel et Notre-Dame is part of an exhibition at the museum, Notre-Dame de Paris: A Laboratory for Restoring Cathedrals (until 2 March 2025)examining the monument’s 19th-century makeover and the role it played in inspiring artists to look anew at the Middle Ages.

Childe Hassam, Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris, 1888 (1888) Courtesy of Detroit Institute of Arts

Childe Hassam

Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris, 1888 (1888)

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

Childe Hassam was America’s premier Impressionist, but when he moved to Paris in 1886, intent on studying at an upscale private art school, he was on track to become a more traditional academic painter. By the time he returned to the US in 1889, he was ready to depict the American landscapes and cityscapes of his native north-east with a full-fledged Impressionist’s eye.

Hassam’s youthful transformation is on view in this Left Bank scene, completed in his 20s, in which he co-mingles Notre-Dame’s monumental towers with modern urban details, including plumes of steamboat smoke and a skeletal streetlamp.

Charles Meryon, The Apse of Notre-Dame, Paris (1854) Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

Charles Meryon

The Apse of Notre-Dame, Paris (1854)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

France’s supreme etcher of the 19th century, Charles Meryon turned his colour-blindness into an asset. After travelling the world as an officer in the French Navy, he returned to Paris and became a professional artist, with Notre-Dame emerging as a recurring motif. This near-rustic view of the cathedral’s nave and flying buttresses shows the cathedral just before it got its signature spire.

Meryon—who ended his life in an asylum—is most admired for his atmospheric renderings of Parisian architecture, using the etching format’s ability to modulate light with shade to highlight architectural details. This take on Notre-Dame is considered his masterpiece.

Eugène Atget, Notre-Dame depuis le quai de la Tournelle (1923) Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

Eugène Atget

Notre-Dame depuis le quai de la Tournelle (1923)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

France’s pioneering documentary photographer, whose life spanned from the reign of Napoleon III to Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 transatlantic flight, moderated a natural but harsh surrealism with unmistakable longing.

His vision of Paris manages to look both ancient and fragile—nearly geological and vanishing before our eyes.

It was only in the last few years of his life that he started photographing Notre-Dame with some regularity, often shooting it from a distance, or else, as in this image, in an odd, oblique way, allowing its famous flying buttresses to turn into strange tendrils.