Half a century after plans were first made, Milan will open a major new museum for Modern and contemporary art this month. The Palazzo Citterio, a grand 18th-century residence less than 200m from the Pinacoteca di Brera, is set to be inaugurated on 7 December, the feast day of Milan’s patron saint.

The development marks the realisation of what has long been described as “Grande Brera”, a new cultural complex with the Palazzo Citterio, Pinacoteca di Brera and the Braidense library—which, like the new museum, falls under the Pinacoteca’s direction—at its heart.

The aim is “to create a large museum complex in Milan on the model of Florence and Rome in terms of visitor numbers and revenues”, Angelo Crespi, Brera’s director, tells The Art Newspaper. “The Uffizi [in Florence], in 2023, had revenues of €63m. The Colosseum [in Rome] was close to €100m. Brera, on the other hand, reached just €5m that year.”

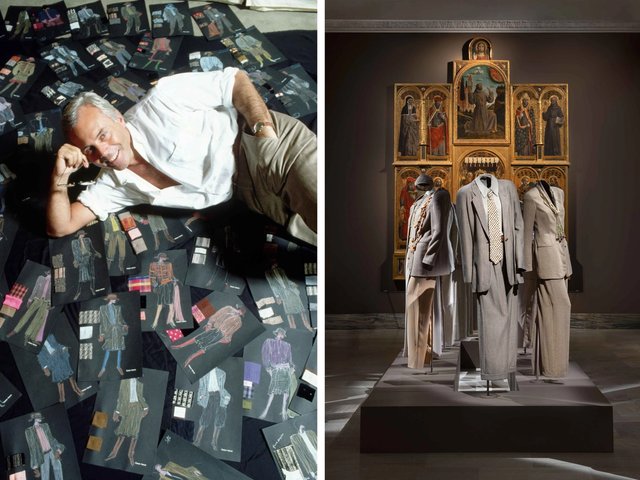

With its collection of works by Caravaggio, Titian and Bellini, the Pinacoteca di Brera is one of Italy’s most prestigious museums. Ticket holders will now have access to a further 200 Modern and contemporary works at the Citterio, including Pablo Picasso’s Head of a Bull (1942), a 1919 still-life by Giorgio Morandi, Umberto Boccioni’s Rissa in Galleria (1910) and Pellizza da Volpedo’s La Fiumana (1898), a preliminary study for the artist’s famous oil painting Il Quarto Stato (1901). Works by Amedeo Modigliani and Georges Braque will also be displayed.

While the core of the Palazzo Citterio’s collection is formed by donations made by the Jesi and Vitali families in 1976 and 1984, Brera continues to acquire works for the space. Crespi said these include two Morandi paintings donated by the Vitali family this year and works by Mario Schifano and Arturo Martini that Brera is currently in the process of buying.

Crespi predicts the opening will drive up visitor numbers in the Brera district over the next four years. The Pinacoteca drew 500,000 visitors in 2023, and the Citterio is expected to draw an additional 50,000 next year.

The entire Grande Brera complex received a boost in October when The Last Supper (around 1495-98) by Leonardo Da Vinci, housed 2km from the Brera district, was entrusted to the Pinacoteca as part of a culture ministry shake-up. Crespi says that taking charge of the work—which decorates the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, a Unesco world heritage site—would push total revenues up to €10m and visitor numbers to 1.5 million.

Plans for the Citterio space were born in 1972, when the government purchased the building following a request by Franco Russoli, the then director of the Pinacoteca. A renovation by the British architect James Stirling in the 1980s suffered long delays and was eventually abandoned following Stirling’s death in 1992. A further €23m revamp completed in 2018 was ultimately deemed inadequate because of problems with humidity.

Anticipating the Citterio opening, in September Crespi unveiled a new Grande Brera octagonal logo that will also be used by other independent institutions housed within the Palazzo di Brera site, including the Brera Astronomical Observatory, the botanical gardens, the Lombard Institute Academy of Science and Letters, the Brera Academy and the Archivio Storico Ricordi.

Crespi tells The Art Newspaper that greater autonomy for museums in Italy introduced in 2014 by Dario Franceschini, then the culture minister, had enabled institutions to improve their financial footing.

“The Franceschini reform… has permitted the Uffizi to become one of the most important museums in the world, not only in terms of its collection but also in terms of its income and visitor numbers,” he says. “Many used to complain that [all] Italian museums were unable to generate [collectively] as much revenue as the Louvre [in Paris]. Today Italian museums generate important revenues.”