A woman artist who was “discovered” three years ago after making art for more than 40 years says she is “beyond happy” to be the subject of a major retrospective at National Galleries Scotland.

Everlyn Nicodemus, 70, was working in a care home in Edinburgh to pay the bills when a coincidence led to her “discovery” by a London gallerist. Now, paintings that have been in storage for decades are hanging alongside new works in a show occupying the whole ground floor of the National Galleries Scotland's Modern One gallery building.

“I am still in—shall I call it shell-shock?” Nicodemus tells The Art Newspaper at the exhibition, which runs until 25 May 2025. “I still can’t believe that this is happening while I’m alive and I’m witnessing it. For a woman artist it is very rare to have a retrospective in your lifetime; for a Black woman, almost unknown. I wake up and pinch myself.”

Everlyn Nicodemus, Together (1985) © the artist, courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery London and Rome

Symbolist, figurative style

Nicodemus was born in Tanzania in 1954, and moved to Sweden when she was 19. It was on an extended visit back to Tanzania in 1980 that she started painting, and had her first solo exhibition later that year at the National Museum in Dar es Salaam after she button-holed the curator and asked him to give her a show. From the start, she worked in a distinctive symbolist, figurative style, exploring women’s experience, trauma and healing.

After a “nomadic” life that took her to France, Germany and Belgium, she settled in Edinburgh 15 years ago with her Swedish husband, the art historian Kristian Romare. Although she was unable to paint for 25 years because she could not afford a studio, she never stopped working, making textile pieces, drawings and sculptural assemblages.

Even when I was working in the care home, I continued with this elemental Arte Povera, using whatever was available, whatever I could affordEverlyn Nicodemus

She attributes her success to the fact that she never stopped making art. “I didn’t stop creating, despite not having a gallerist or museums interested in my work," she says. "Even when I was working in the care home, I continued with this elemental Arte Povera, using whatever was available, whatever I could afford.

“I think it is a drive which is in most artists. It is probably as strong as what makes us want to become parents, or what makes us love unconditionally. There is no culture on earth that doesn’t create.”

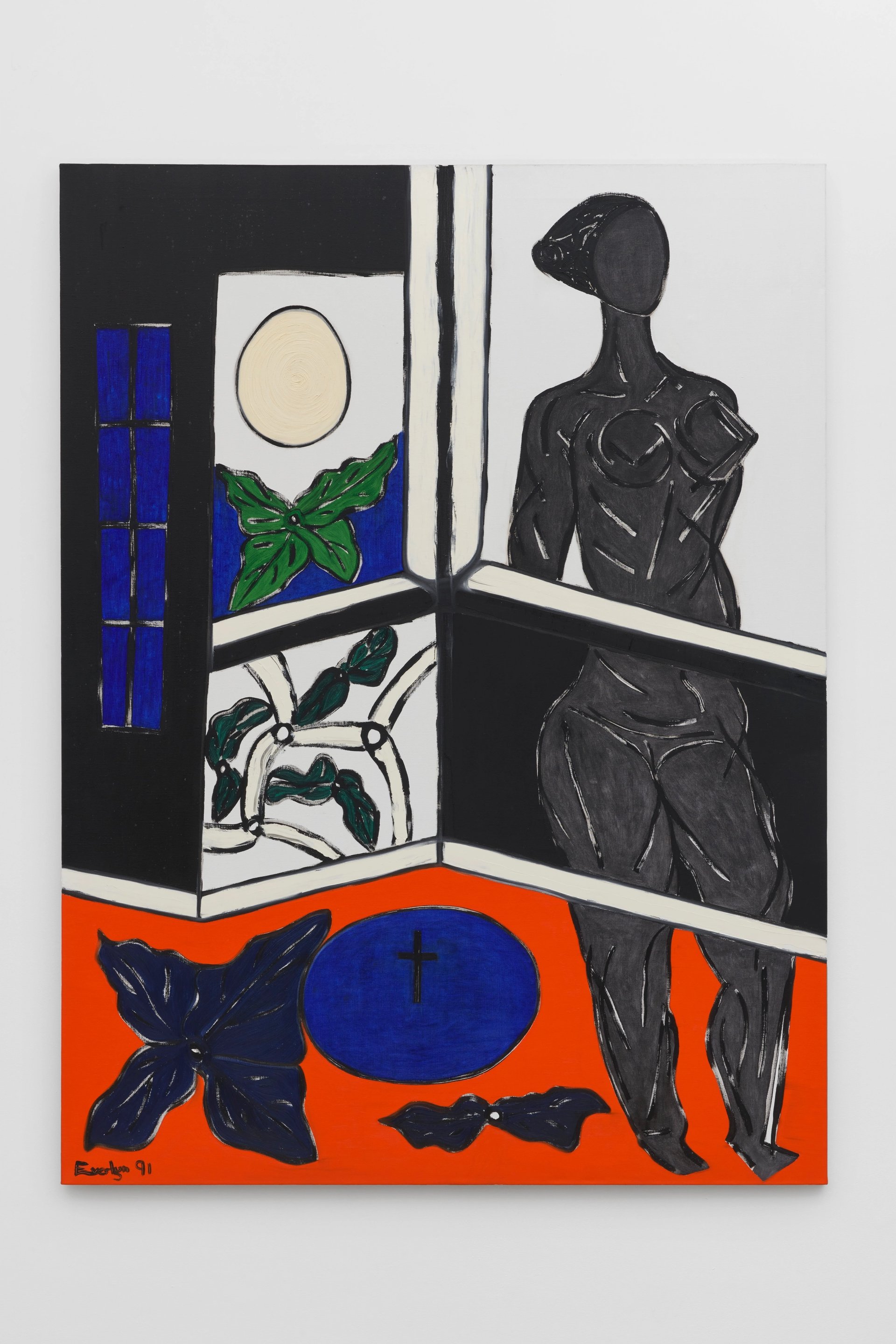

Everlyn Nicodemus, The Wedding 45 (1991) © the artist

Having used her savings to fund her PhD in Modern African art and Black cultural trauma at Middlesex University, and to support her work as a pioneering art historian, she retrained as a care worker after her husband died in 2015. She said she was “almost giving up” when she received a call from the London gallerist Richard Saltoun in 2021, who had read about her in a book on women’s art by the Belgian curator Catherine de Zegher.

“His gallery manager came to visit me in my little one-bedroom flat," she says. "I showed her what I was creating, what was under my bed. She took photos on her phone and sent them back to Richard, and he offered me a contract immediately.” She was then able to open the eight storage containers that held her life’s work, carefully catalogued by her husband.

Award-winning work

Saltoun exhibited her work later that year at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, where it was hailed as a revelation, and her self-portrait Självporträtt, Åkersberga (1982) became the first painted self-portrait by a Black female artist to be acquired by the National Portrait Gallery. In 2022, she won the Freelands Award to support the exhibition in Edinburgh, a version of which will be presented at WIELS, Brussels, in autumn 2025.

We want to celebrate a life’s work and the healing power of artStephanie Straine, National Galleries Scotland

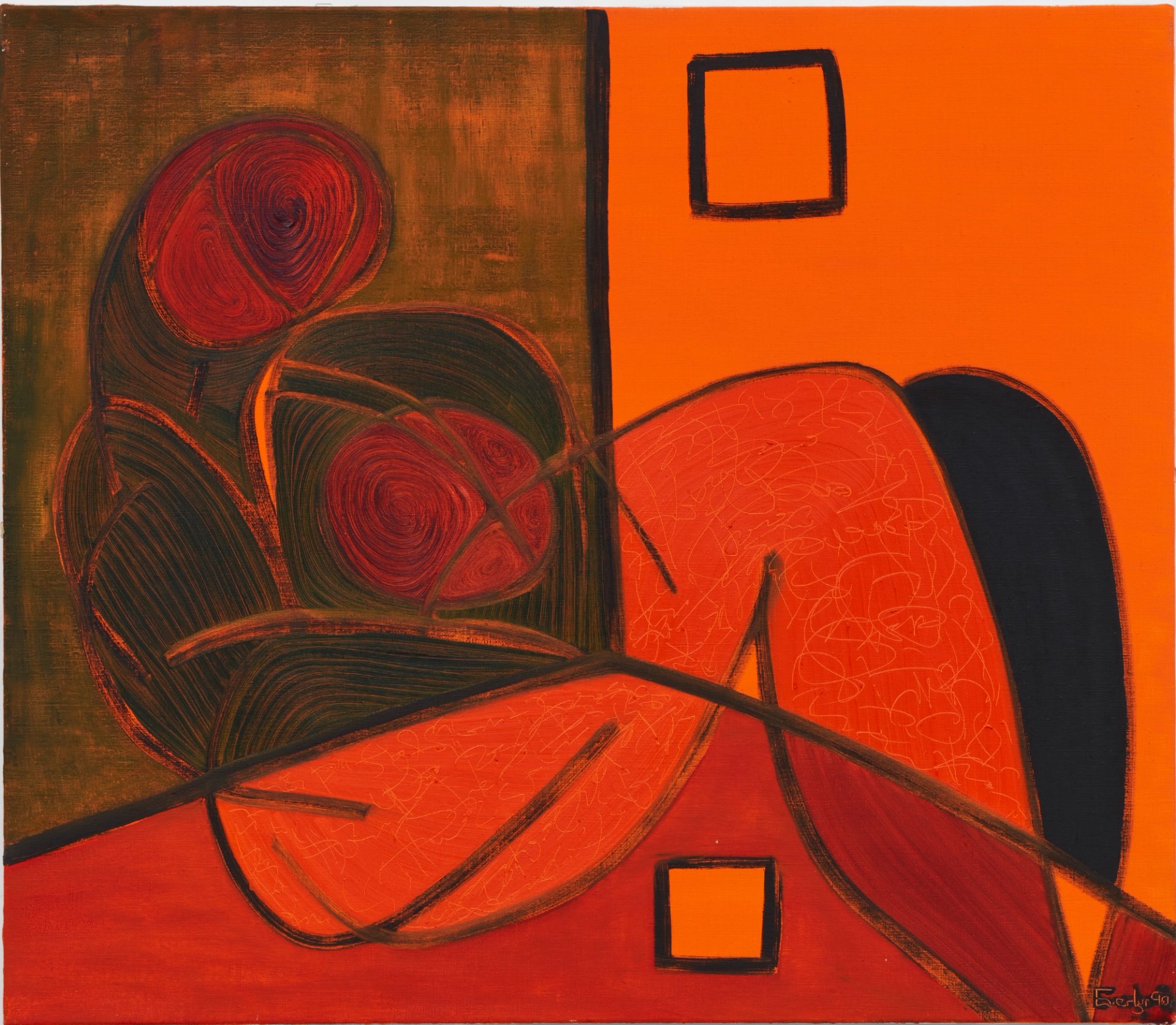

Everlyn Nicodemus, Silent Strength 38 (1990) © the artist, courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery London and Rome

Stephanie Straine, the senior curator of Modern and contemporary art at National Galleries Scotland, says: “Everlyn’s story follows the cliché of female artists not getting the recognition they deserve until later in their career, but we don’t want to focus on that; we want to celebrate a life’s work and the healing power of art.

“She never let her circumstances reduce the ambition of her work. That’s an important part of why the work is so exciting; it’s just so uncompromising.”

Nicodemus says that, while her scholarship was taken seriously, her art met with “a lack of curiosity, a neglect”. She pays tribute to her husband and her close friend, the art historian Jean Fisher, who died in 2016, because they “never stopped supporting me”.

“I promised them I would never stop creating and I haven’t stopped, but I wish they were here to celebrate this with me.”