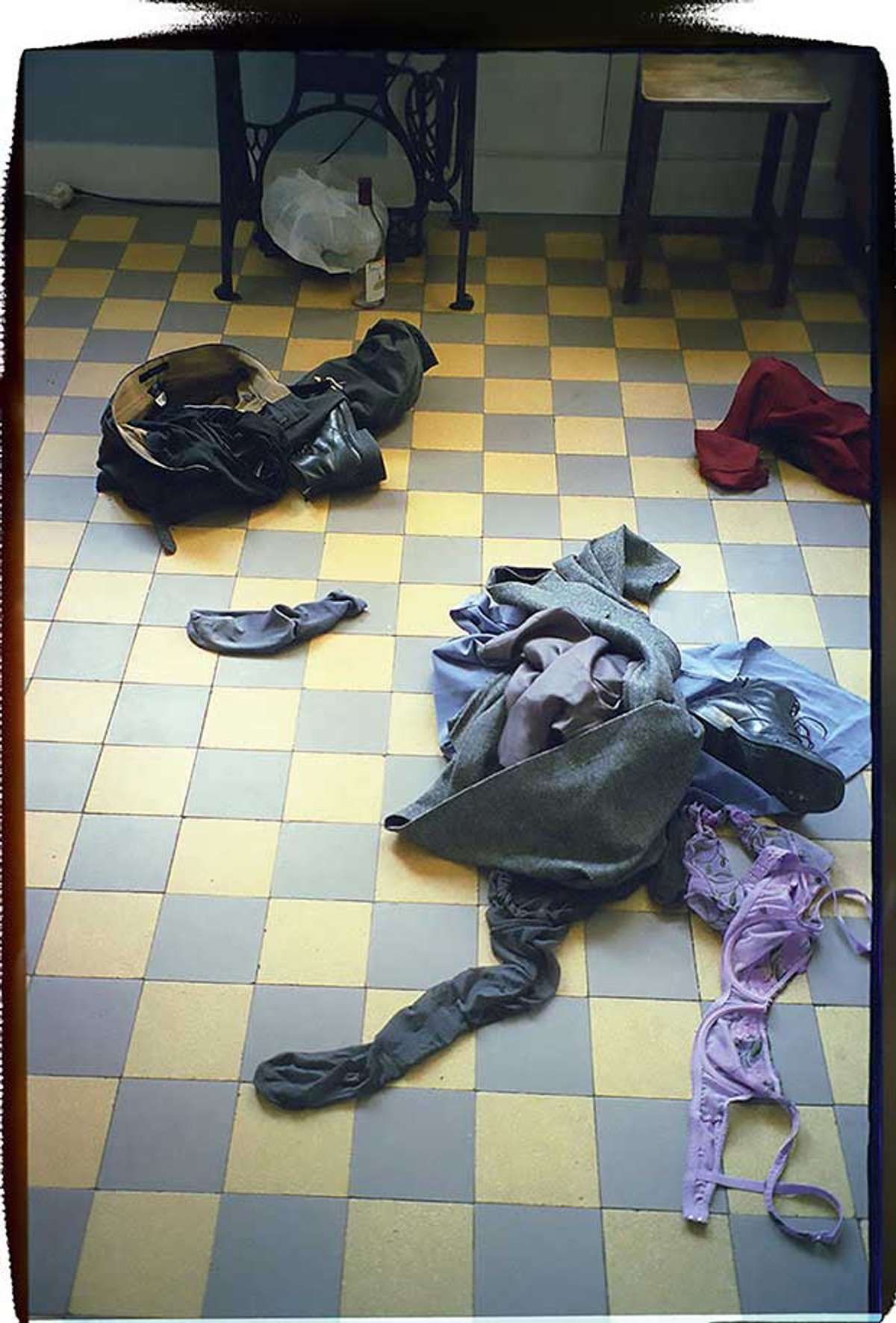

At first glance, the photographs in Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie’s The Use of Photography do not seem particularly useful. They show what most people would keep from public view, the messy prologues to nights of lovemaking: piles of bunched-up clothes; shirts, trousers, underwear, a stray sock all dropped on the floor; dirty dishes, tangled power cords and scattered pens from an overturned cup. Taken the morning after, these images—disorderly topographies of past desires—preserve the traces of a love affair that, we soon find out, lasted for less than a year.

There are 14 pictures in the volume, each accompanied by a set of earnest comments, written separately by the (now ex-) lovers. For readers with less developed libidos, or those who like to fold their clothes before they go to bed, there is something a little relentless, in a very French sort of way, about this archive of undress, a feeling akin to having arrived too late for a party to which one was not invited in the first place. But Ernaux, (born 1940 in Lillebonne, Normandy), the doyenne of solemn sex and winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature, would not have wanted it any other way. She began dating her compatriot Marie, a journalist and photographer, in January 2003, and from the beginning it seems to have been clear that they would not let their liaison remain undescribed. First published in 2005, as L’usage de la photo, their unclassifiable book has finally become available in English, in Alison Strayer’s crisp, elegant translation.

The idea to take pictures, not of themselves or of each other but of their discarded things, was a joint one, as were the rules Ernaux and Marie established, such as never to move any item for aesthetic effect. It appears that the majority of the photographs in the book were the work of the professionally trained Marie. But Ernaux had in fact long been thinking of herself as a photographer too, with words as well as her camera—see, for example, her 1993 book Exteriors, a precisely observed record of interactions among the residents of Cergy-Pontoise, near Paris, where Ernaux still lives.

It was in Ernaux’s house in Cergy-Pontoise that most of the photographs in The Use of Photography originated: in Ernaux’s hallway, kitchen, living room, study and bedroom. (Was there any place they did not do it?) “No two clothing compositions are alike,” asserts Ernaux. And yet there are motifs that recur in many of them, such as the lovers’ shoes, featured either singly or in pairs—Ernaux’s high-heeled pumps, Marie’s heavy Doc Martens-style boots, with laces stylishly undone. These are not the rumpled work shoes made famous by Vincent van Gogh’s paintings, not the coarse clay-covered farmer’s boots photographed in 1936 by Walker Evans for James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—footwear that carries the imprint of those who use it. There is something clinical, even unromantic, by comparison, about Ernaux and Marie’s pictures, as if the things they portray had very little to do with their owners.

But if there is a whiff of privilege that attaches itself to The Use of Photography (do these people have any work to do?), that impression is undone by another, chilling story woven into the book’s narrative. Marie and Ernaux met after Ernaux’s breast cancer diagnosis, when she had already lost her hair, carried a catheter under her armpit, and was facing surgery. During that time, Ernaux’s body was constantly photographed, in the form of X-rays, ultrasounds, scans and MRIs. What a relief, then, to delve into the world of objects, to have the camera’s lens focused, for once, on external things rather than one’s inner organs. Still, the prospect of death, absence made absolute, continued to lurk in the background. “For months,” wrote Marie, “we lived together as a threesome, A [Annie], death, and me.” (In a twist of fate, while Ernaux survived her cancer, Marie, the younger by 20 years, has since died.)

In The Use of Photography, Ernaux expresses her hope that houses might somehow retain the memories of those who once lived and loved there. But the photographs collected here suggest otherwise. They open up the sobering possibility that, once we are gone, for all the pictures we might take, for all the words we might craft to explain them, nothing much may remain of us—that, in the eyes of those who come later, anyone might have walked in our shoes.

• Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie, translation Alison L. Strayer, The Use of Photography, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 136pp, 14 b/w illustrations, £12.99 (pb), published 10 October

• Christoph Irmscher is a critic and biographer