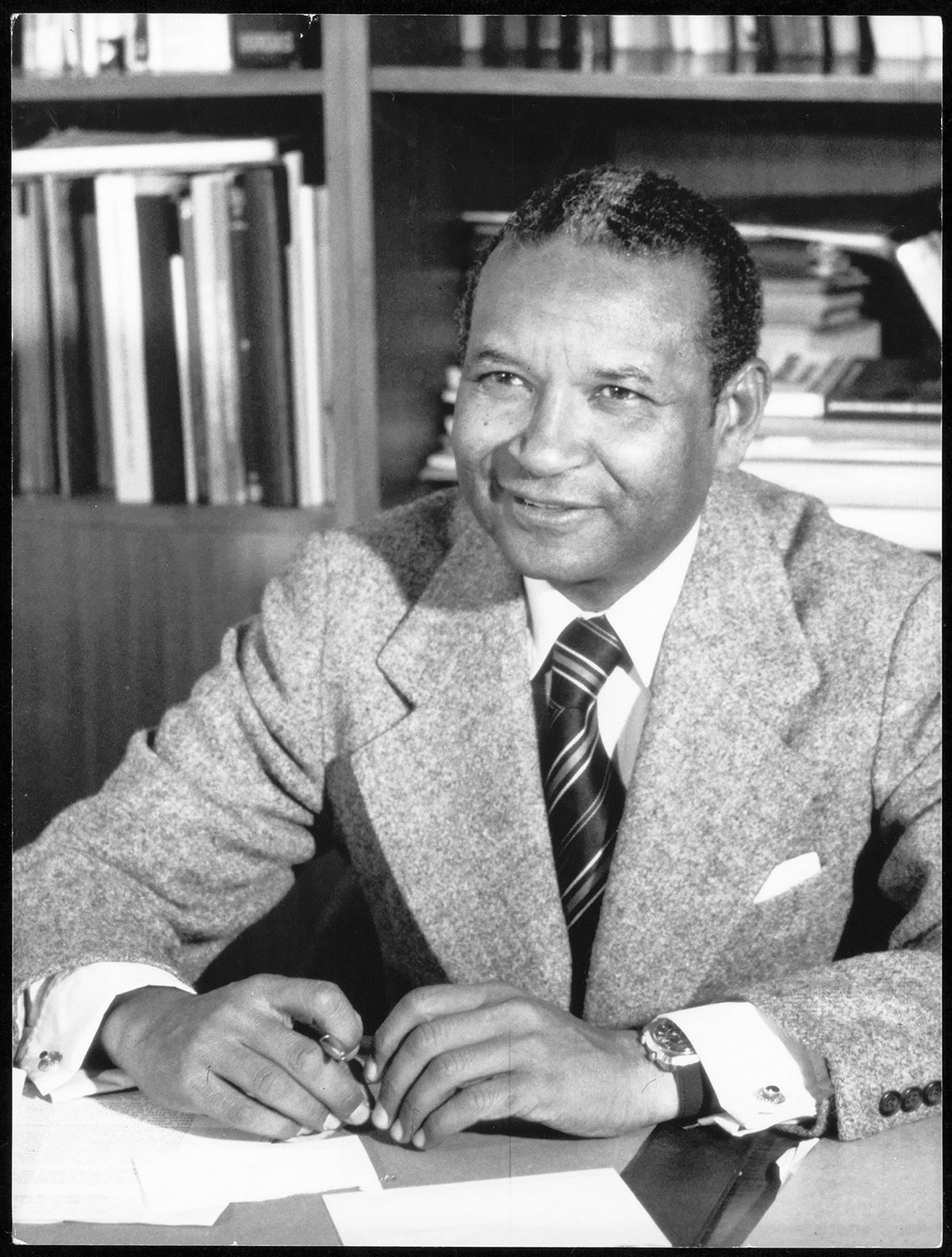

Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow was a high-profile, often controversial but ultimately progressive director-general of Unesco. A self-made leader who rose from an impoverished background, M’Bow was the first sub-Saharan African to head an important United Nations (UN) organisation when he was elected to run the UN’s educational, scientific and cultural agency in 1974.

While M’Bow’s defenders remember a determinedly multilateralist intellect who pivoted Unesco away from Western interests at the dawn of globalisation, his critics recall a fearsome institutional operator who bent the organisation to his will, and whose tenure was mired by repeated accusations of scandal, financial irregularities and political machinations. In the mid-1980s, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher pulled the US and UK respectively out of Unesco, in protest at M’Bow’s management style, which included close connections with authoritarian nations during the Cold War.

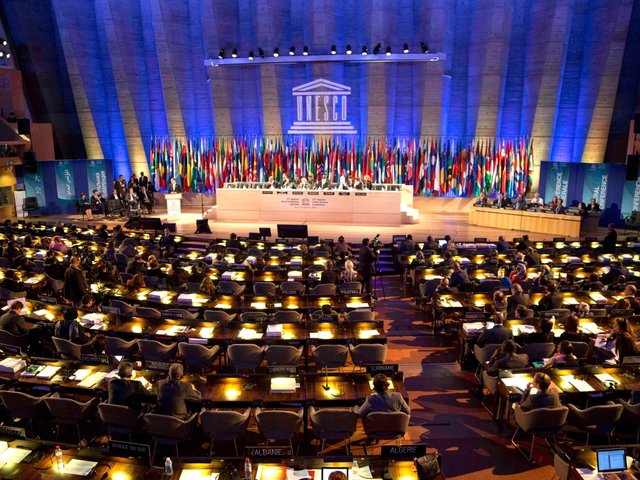

Unesco was founded in 1945 as part of the fledgling UN to promote peace through international collaboration in the areas of education, science, culture and communication. Its core mission includes the safeguarding of both tangible and intangible heritage, including historical landmarks and artefacts, and it works closely with the International Council of Museums, a global body focused on museum conservation and the protection of cultural heritage from illegal trafficking.

Solidarity between peoples

In a statement, Audrey Azoulay, the present Unesco director-general, paid homage to “a profound humanist” who “forcefully defended the need for solidarity and equal dignity between peoples and cultures”.

M’Bow led Unesco in the decade after a number of nations across Africa and Asia gained independence from colonial European rule. He was instrumental in bringing these newly independent states into the fold. During his tenure, Unesco’s membership grew by 27, from 126 nations to 153. African countries including Mozambique, Namibia, Equatorial Guinea and Botswana all joined Unesco during this period.

The French journalist and diplomat Pierre Kalfon, a former speechwriter for M’Bow, wrote of his employer’s ascent: “The path that led the small farmer from the African Sahel to the head of one of the United Nations’ most prestigious organisations is representative of the emergence of a world that had long been subjugated, despised or even ignored: that of the dispossessed.”

The French air force and the Sorbonne

M’Bow was born into a poor, rural Muslim family, in the Senegalese capital of Dakar in 1921. He grew up on a farmstead near Louga, a small city in north-western Senegal. An able student, he was educated at a French colonial school and was still a teenager when—following the path of his father, Fara Ndiaye M’Bow, a First World War veteran—he volunteered for the French Army at the outbreak of the Second World War. He fought for the French airforce during Operation Dragoon, serving as an airport mechanic during the landings along the Provençal coast between Toulon and Cannes—a critical element in the Allied defeat of Nazi Germany.

M’Bow’s willingness to take up arms for his coloniser afforded him a world-class education. Shortly after he was demobilised, he passed the baccalaureate and enrolled at the Sorbonne, in Paris, to read geography and history. During the 1950s, the young, ambitious and highly educated war hero ascended quickly through the government of Senegal, which was in the throes of an independence movement.

Senegal formally achieved independence on 20 August 1960 when the country’s National Assembly withdrew it from the Mali Federation. Over the next decade, M’Bow was central in establishing the new state’s primary education system. By the late 1960s, he was made minister of national education and appointed assistant director-general for education at Unesco in 1970 before being elected as director-general in 1974.

Champion of restitution

The policy achievements of the M’Bow era were numerous and far-reaching. The World Heritage Committee, set up by the 1972 World Heritage Convention, was fully established under his tenure in 1976; the committee today selects the global locations to be listed as Unesco World Heritage Sites. In 1978, he established the Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in Case of Illicit Appropriation, a key body in modern-day restitution cases. In a speech at a UN conference in Paris, he called for artefacts held by institutions in the northern hemisphere to be restored to their rightful home, calling the legislation “a plea for the return of an irreplaceable cultural heritage to those who created it”. In 1981, he launched the International Programme for the Development of Communication.

Perhaps most significantly, M’Bow called for what he termed “a new world information and communications order”. He set up a commission headed by the Irish Nobel Peace Prize laureate Séan MacBride, a co-founder of the civil rights charity Amnesty International, who published a white paper titled Many Voices, One World in 1980. The report sought to suggest ways that Unesco could assist developing countries in furthering their own news-gathering and media ecosystems. But it also proposed that journalists working for Western publications be forced to comply with a centralised licensing system.

The report sparked outrage across the legacy media, which decried M’Bow as a draconian censor. Yet he did not give an inch. In an interview with United Press International in 1980, he said that “the realities of the Third World and the aspirations of the Third World” were ignored by the big media organisations in the US, France and the UK. He retained this view for the rest of his life. In the 2021 book A Legend to Tell, M’Bow told the author Mahamadou Lamine Sagna, the inaugural director of the Africana studies programme at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute: “If you go to any African country, you will get news produced by the North.” This had to change, he argued, because “the North distributes according to its own interests”.

Entourage

Alongside such legislative achievements came plenty of questionable budgetary practices. Surrounding himself with loyalists who owed their rise to his largesse, M’Bow centralised the agency’s operations around its Paris headquarters, from where more than 80% of its spending initiatives were decided. Citing apparent security concerns, M’Bow converted the top two floors of the agency’s central offices into living quarters for his family. He appropriated six official cars and developed an entourage that was larger than that of the secretary-general of the UN itself. A family member was his official head of personnel. On 1 March 1984, in an editorial for The New York Times titled “Airing Unesco’s Closets”, the foreign affairs correspondent Flora Lewis accused M’Bow of a “peculiar form of tyranny”. Unesco under M’Bow, Lewis wrote, was “a totally politicised, demoralised bureaucracy whose chief concern is to provide cushy jobs for politicians unwanted at home”.

Throughout his tenure, M’Bow had a ready response to such critics: they were colonialists. Shortly before Reagan pulled the US out of Unesco in 1984, M’Bow accused Jean Gerard, the US representative, of treating him “like an American black who has no rights”. The UK followed suit and pulled out in 1985. (The UK returned in 1997 and the US recommitted to the agency under the presidency of George W. Bush in 2003.)

A vainglorious populist from the bowels of a bloated UN, or a visionary with the determination to bring nations together through culture and education? In death as in life, Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow and his legacy are the subject of debate.

• Amadou-Mahtar M’Bow; born Dakar, Senegal 20 March 1921; married 1951 Raymonde Sylvaine (two daughters, one son); died Dakar 24 September 2024