Activism against fossil fuel extraction in the art world has intensified in recent years, with groups such as Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil using museums as targets and backdrops for protests against oil and gas production. Although the protests have focused on ongoing and future development, there are millions of orphaned and abandoned oil and gas wells across the US, most which were installed before environmental and cultural protection laws were enacted starting in the 1960s. They continue to pose severe risks to heritage sites, the environment and the well-being of communities that have been subjected to greenhouse gas emissions and air and groundwater pollution.

Earlier this year, the federal government passed the Abandoned Well Remediation Research and Development Act, a programme to examine the impact of orphaned wells, the exact number of which is still unknown. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates there are around 3.4 million orphaned wells nationwide, in addition to between 300,000 and 800,000 wells that have not been recorded or mapped. The number of orphaned wells reported to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) is much lower, totalling fewer than 120,000 wells across 27 states.

Although its dataset is incomplete, the USGS cites an Environmental Defense Fund analysis estimating that around 14 million people live within one mile of an orphaned well. Some wells are located on private or remote public land, making tracking them more challenging. After a well has been recorded, it is considered ‘orphaned’ if it has been out of production for an average of 12 months, is unplugged, and no one is responsible for managing it for future reuse or plugging.

There are tremendous concerns for the preservation and conservation worlds

Although orphaned wells are present nationwide, the issue particularly affects Native American communities. Last year, President Joe Biden’s administration rolled out the first phase of the $4.7bn Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which includes state and federal programmes and a $150m tribal programme to help Native American communities plug or reclaim orphaned wells, restore the soil in affected areas, decommission or remove associated infrastructure, document previously unrecorded wells and protect archaeological and cultural sites.

Disproportionate burden

Deb Haaland, the US Secretary of the Interior and the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, stated earlier this year that Indigenous communities have been “disproportionately burdened by environmental pollution” and that the programme ensures tribes will be able to “make their own decisions about how to address the health and safety of their people, improve economic growth and realise their vision for the future”.

Most orphaned wells are concentrated in the Midwest, the Western Gulf Coast, the Southern Plains and Appalachia. Pennsylvania, where oil production dates to the mid-1850s, ranks the highest of all states, with nearly 9,000 recorded orphaned wells and up to an estimated 750,000 abandoned wells. The presence of orphaned wells has also been particularly concerning in the Southwest, where they—in addition to ongoing oil production—have had a severe but mostly undocumented impact on heritage sites.

A report published by the non-profit Archaeology Southwest earlier this year focused on a region known as the Lands Between in southeast Utah and the proximity of orphaned wells to the nearly 50,000 sacred, cultural, archaeological and historic sites in the area, which spans 350,000 acres and is the ancestral homelands of the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, Laguna, Rio Grande Pueblos, Ute, Navajo and Paiute tribes.

“There are thousands of these wells in zones around the Southwest, and this isn’t a problem that’s disappearing soon,” says Paul F. Reed, the archaeologist who compiled Archaeology Southwest’s report. The most shocking aspect of the process, he adds, is how the wells get passed around. “The top-tier producers come and get the highest profit of oil and gas out, then come the second and third producers, most of whom are operating at marginal levels of profit and sometimes at the level of bankruptcy,” he says. “When the tertiary producers pull out, it’s up to the state or the feds to clean it up, and there’s no penalties for any of these companies.”

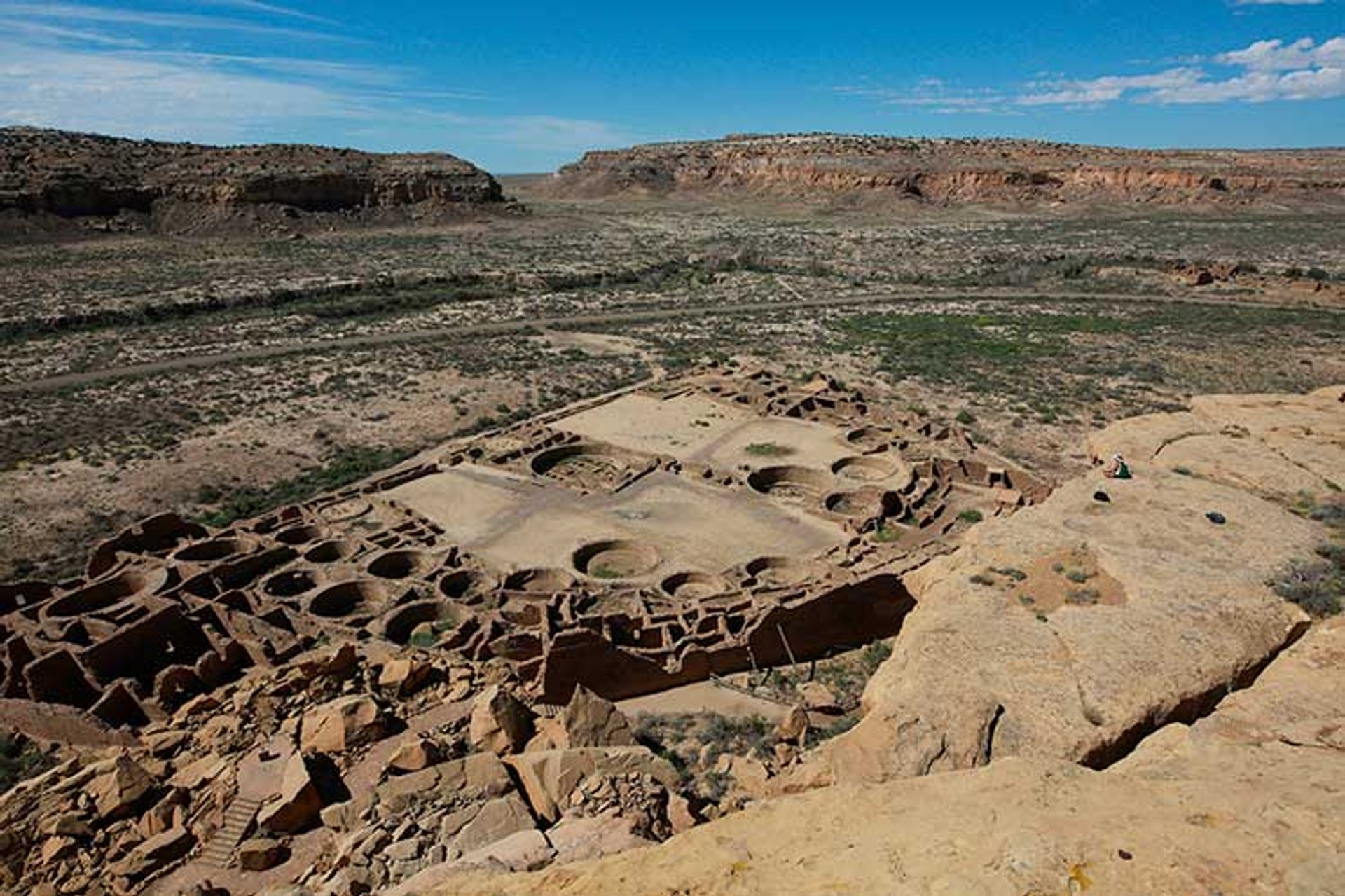

Sites like the Chaco Culture National Historical Park and the Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico, where more than 200 orphaned wells have been discovered in close proximity to protected areas, have been at times mismanaged by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

“There are cases where federal and tribal managers have talked about damage to cultural sites in this area, but at this point it’s still anecdotal information,” Reed says. “I’ve been to areas where I found bulldozed cultural sites, but there still isn’t much systematic documentation on them. At some point, our organisation wants to do a report of that scale.”

Although US oil production has surged to record highs under both the Trump and Biden administrations, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law has been a significant step in remediating some of the impacts of oil and gas development while ensuring better solutions for the future. In the leadup to the 2024 US presidential election, environmental and preservation groups have voiced concerns that Republicans could again cap funding for environmental and heritage programmes, open more federal land to oil and gas leases, and reverse the higher bond requirements required by the infrastructure law. Between 2017 and 2019, the Trump administration sold over 40,000 acres of new leases to oil and gas developers in the Southwest.

Chaco Culture National Historical Park has scores of orphaned wells nearby

Associated Press/Cedar Attanasio

“We could see an overturning of not just infrastructure laws but cultural resource and environmental protection laws that have been in place for over 50 years,” Reed says. “There are tremendous concerns for the preservation and conservation worlds.”

Spectres in the landscape

Some artists, such as the Missouri-based photographer Meghan L.E. Kirkwood, have explored the complexities of the issue of orphaned wells in their work. Kirkwood began an ongoing series of photographs in 2020 documenting orphaned wells in the town of Oil City in Louisiana, a state with a long history of oil production and where more than 4,000 orphaned wells have been recorded, most of which have blended into the landscape. Kirkwood’s black-and-white photographs are haunting and minimal, presenting the orphaned wells as spectres in the landscapes on which they are encroaching.

“What interested me was doing this project in a place where people still have a tight connection to the oil industry, and not being one-dimensional about the approach,” Kirkwood says. “There’s so much urgency around this issue, but there’s also a need for nuance to make work that makes people really reflect on what’s happening. We risk putting people off if it gets to be too one-liner. It’s a complicated part of history that requires complicated work.”