The situation for artists in Myanmar continues to worsen, as civil war convulses the country three-and-a-half years after its military coup. Myanmar’s vibrant cultural community has largely now scattered abroad, with those remaining facing deteriorating conditions.

“The economy is in a state of collapse, leading the currency to weaken almost daily, and petrol queues can reach hundreds of metres or longer,” says Jørn Middleborg, the chief executive of Bangkok’s Thavibu Art Advisory, which works with several Myanmar artists. Only a few exhibitions are still being held, such as at Yangon’s long-standing Lokanat Gallery, but, he says, “obviously, the artists are not able to show anything overtly political or anything slightly hinting at politics. All exhibitions are subject to censorship and government approval prior to being staged.”

The Tatmadaw military junta, which deposed the democratically elected government in a February 2021 coup, has since this February been enlisting civilians into its ranks, in part due to high numbers of defections. In October, the junta conducted a census of the portions of the country it controls, excluding the conflict areas of the northern Shan, Kayah, Kayin and Rakhine states, ostensibly in preparation for new elections in 2025. But the presence of pro-military representatives from the Union Solidarity and Development Party with military guards fuels fears that only junta backers will be allowed to vote and that the census will be used towards the ongoing conscription efforts.

Emigration crackdown

The census and conscription have sped up the flow of refugees out of Myanmar, as has catastrophic flooding from typhoon Yagi, which has displaced more than 235,000 households since September. The junta has cracked down on legal emigration, now requiring an elusive working passport instead of the more accessible visiting passport, driving many to dangerous illegal crossings. Members of the Rohingya minority group continue to face discrimination both at home and in regional refugee camps, particularly in Malaysia, Bangladesh and Thailand. In a particular knife twist, Rohingya are now being made to join the very same army that killed thousands of their kin.

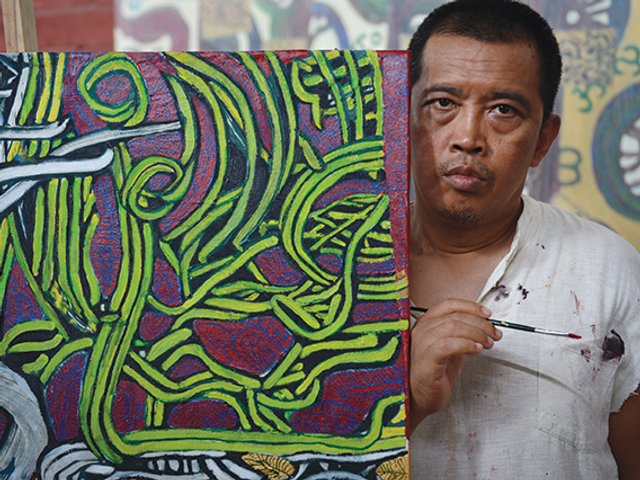

Myanmar’s refugee artists, who are largely either clustered in Thailand or scattered across Europe and the US, struggle to find audiences and markets, despite a handful of high-profile exhibitions. Last year, the British Museum opened Burma to Myanmar (2 November 2023-11 February 2024) in commemoration of the country’s 75 years of independence from the UK. The renowned performance artist Moe Satt, who was jailed by the junta in 2021 and is now living in Europe, at present has an exhibition at Delfina Foundation in London (closed 17 November) that was paired with two mid-October performances at Tate Modern. The current Gwangju Biennale includes a Myanmar Pavilion showing a number of dissident artists such as Htein Lin, Aung Myint and Zaw Win Pe. Htein Lin, who was a political prisoner from 1998 to 2004 and was jailed again in 2022 along with his wife, the former British diplomat Vicky Bowman, joins Moe Satt and fellow Myanmar artist Min Thein Sung in the group exhibition Everyday Practices, at Singapore Art Museum (until 20 July 2025).

These show have “sadly” not increased the profile of Myanmar artists much, says Stephanie Braun, the director of Karin Weber Gallery. Located in London and Hong Kong, it is one of a handful of Asian galleries that have long supported art from Myanmar, along with 10 Chancery Lane, also in Hong Kong, Bangkok’s Nova and Thavibu, Kuala Lumpur’s A+ Works of Art, and Richard Koh Gallery in Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok and Singapore.

It “feels like Myanmar has vanished off the map for many,” Braun says. “If you look at what constitutes ‘South East Asia’ (SEA) for many organisations and art projects, Myanmar is not even on the list. If Myanmar works are part of SEA auctions, estimates and sell-through rates are low and disappointing. [It] feels like the market remains with collectors who have a vested interest in the country; there is virtually no engagement beyond.”

If you look at what constitutes ‘South East Asia’ for many, Myanmar is not even on the list

Middleborg concurs that “the international market for Myanmar art is currently very weak”. Since the coup, the suppression of the Civil Disobedience Movement protests and the ongoing civil war, “many artists left the country including some of the best”. With little tourism and export challenges, the artists remaining have even less chance at sales. Besides Moe Satt, major artists now in Europe include Nge Lay and Aung Ko in France.

Mobile asset

Middleborg says that some art trade does carry on in the country, with both army backers and a neutral middle class using traditional art as a comparatively mobile asset. “It may be surprising, but there is a group of collectors who trade among themselves. I heard the trade was brisk last year after Covid, but has since declined in 2024, probably at least partly due to the weakening of the currency.”

“Thailand is welcoming, though it is always a question of how to deal with visa issues and work permits,” as well as expiring passports. While previous Myanmar migrants to Thailand were labourers in industries like construction, “Thailand is experiencing an influx of Myanmar people with better education and also many who are entrepreneurs,” opening Myanmar restaurants such as Bangkok’s well-known Rangoon Tea House, Middleborg says. “Curators from Myanmar are in Bangkok looking for space and partners to stage exhibitions with.”

Those exhibitions are giving voice to democratic Myanmar’s voiceless, however faintly. “Where there have been art shows outside of Myanmar, they have tended to focus on pro-democracy or human rights angles and are often supported and sponsored by such organisations,” Braun says. In February her London space held the show Against the Tide: Myanmar Art in the Moment, with nine artists including Aung Myint, Htein Lin and Sandar Khine. The show “attempted to focus on the artists in their own right, with their personal narratives—but it is impossible to completely separate from politics.”