Longwood Gardens, one of the largest and most historic gardens in the US, is unveiling a years-long expansion and renovation on 22 November. The $250m project has transformed the vast public space consisting of more than 1,100 acres of gardens, woodlands and meadows in south-eastern Pennsylvania. Notably, this includes the careful reconstruction of the late Brazilian artist and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx’s 1992 cascade garden, which had fallen into disrepair in the past three decades.

Longwood has a storied history. For thousands of years the Lenni Lenape tribe hunted and fished on the land, before they were forcefully removed from Pennsylvania in the 18th century (related artefacts, like quartz spear points, have been found throughout the property and are displayed today in Longwood’s Peirce-du Pont House). A Quaker farmer named George Peirce purchased and cleared more than 400 acres of the land in 1700; a brick farmhouse built by one of his sons in 1730 still stands today. Peirce’s heirs were curious about natural history and began planting wild and rare specimens on the grounds, creating an arboretum that covered 15 acres by the mid-1800s. But the family eventually lost interest in maintaining the property, and the arboretum began to deteriorate. In 1906, the industrialist Pierre S. du Pont purchased the land to save its trees from being sold for timber. Over the years he facilitated the creation of extensive gardens, which he opened to the public in 1921, as well as a foundation to oversee a series of expansions and additions—including a famous 600-jet fountain that puts on choreographed water shows. Longwood was added to the US’s National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

The gardens’ most recent revamp was spearheaded by the architecture firm Weiss/Manfredi in collaboration with the landscape architects Reed Hilderbrand, who worked with the Burle Marx Landscape Design Studio to oversee the transfer of the cascade garden to an enlarged custom glasshouse. The cascade garden comprises 16 waterfalls that flow into a pool, framed with climbing vines and clusters of striking bromeliads. Most of the original plants have been replaced over the years, as some had grown too tall for the glasshouse and were crushed against the ceiling; others were badly burnt due to poor climate control.

Burle Marx’s newly reconstructed cascade garden Photo: Judy Czeiner, courtesy Longwood Gardens

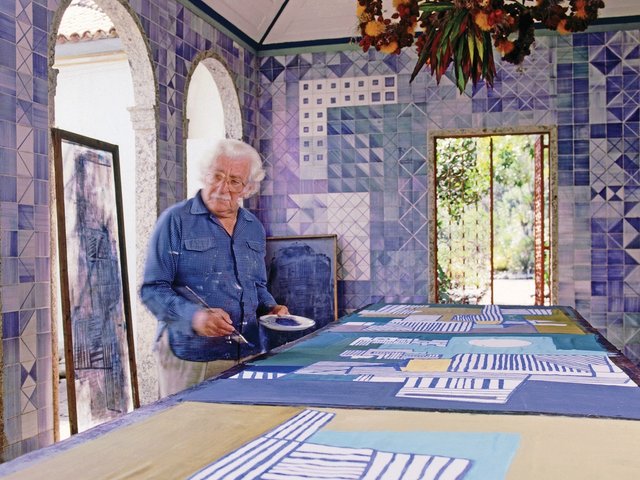

Sharon Loving, Longwood’s chief horticulture and facilities officer, was there when Burle Marx completed his original garden, recalling that it was “like watching a magician work”. Burle Marx, who died only two years after completing the cascade garden, had first made connections with Longwood’s trustees through a Pennsylvania-based liaison in the late 1980s. Some of them travelled to Rio de Janeiro to observe how Burle Marx worked. It was first proposed that he design the East Conservatory at Longwood, but that project fell through, as his studio felt that Burle Marx’s Modernist approach to landscape design would not be appropriate for the space. Instead, he opted to construct a cascade garden inside a 3,500 sq. ft former desert glasshouse with a 22ft ceiling.

“He arrived and did not follow the planting plan as closely as we anticipated,” Loving says. “We were asked to source enough plants to fill the house twice. He would walk around the space, sometimes taking us by the arm, or lie down in the shade. Then he would instruct the whole team to grab plants and would begin ‘painting’ the plants on the wall, telling us this one should go here or there. It was very intuitive and organic. He said he saw the project like the crescendo of a symphony. He wanted it to be powerful, where you would have the sound of water and all your senses would be engaged. He combined his plant knowledge, his skill as a landscape architect and all of his expertise in music and art when he worked.”

The $6.5m revamp of the cascade garden involved updating its mechanical and fountain systems to stabilise climate, resetting most of the original schist of the planting beds and garden walls, and reinstalling around 180 plants salvaged from the original glasshouse. It also lifted the peak of the garden to a height of 30 ft and expanded its overall footprint to 3,800 sq. ft, adding additional plants to give it the “rainforest experience” that Burle Marx had envisioned. A central path and ramp were also constructed for accessibility.

The newly preserved cascade garden Photo: Becca Mathias, courtesy Longwood Gardens

Treading lightly

Burle Marx’s concept drawings, construction design, planting plans and later 3D scans of the original cascade garden, which are held in Longwood’s permanent collection, greatly informed the project. The architects also worked with Anita Berrizbeitia, a landscape architect and Burle Marx scholar, to outline the most significant features of the garden. A series of workshops followed to decide which parts of the garden could be changed and which should be closely reproduced.

“We knew the garden would need to be dismantled, and realised how important it was to tread lightly and carefully,” says Kristin Frederickson, a principal of Reed Hilderbrand. “Reconstruction assumes that a garden has been lost and will be rebuilt, while preservation assumes a garden is in place and you’re protecting it. This was somewhere in the middle.” She adds that a point of importance was retaining the “sense of immersion as the changes were executed”.

Reed Hilderbrand was instrumental in consulting on the cascade garden’s long-term conservation, assisting with fine tuning the design in collaboration with Weiss/Manfredi, which sought to create “a new home for the garden where it was not only better located but also environmentally and architecturally much more conducive to the beautiful work that Burle Marx did”, says Marion Weiss, a cofounder of Weiss/Manfredi.

Exterior view into the cascade garden Photo: Holden Barnes, courtesy Longwood Gardens

Together with the cascade garden, a centrepiece of Longwood’s expansion and renovation project has been the addition of the West Conservatory—a 32,000 sq. ft space said to be one of the largest in the US, containing several gardens, pools, fountains and nearly 2,000 glass panels. Like Burle Marx’s garden, the conservatory is a “living and breathing” glasshouse, according to Longwood, with automated walls and roof panels. Longwood has also added 17 acres to its gardens, an education and administrative building, a bonsai courtyard, a renewed seasonal restaurant and other features.

Longwood will hold a design symposium in October 2025, bringing in representatives from Weiss/Manfredi and Reed Hilderbrand as well as other speakers, to discuss Burle Marx’s legacy and impact on 20th-century landscape architecture and the importance of the cascade garden—his only such surviving work in the US.