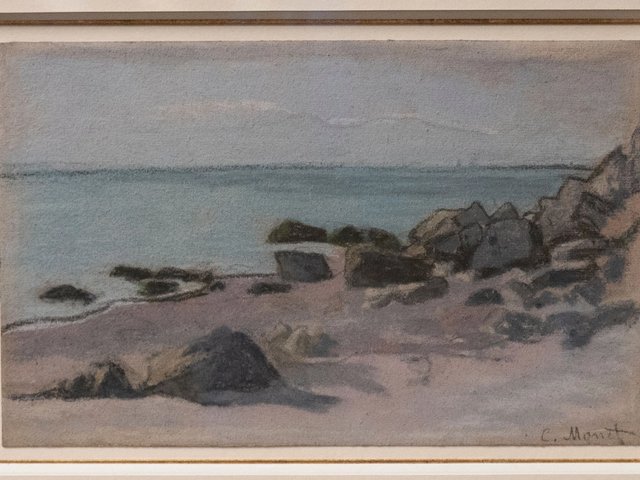

Basel’s Kunstmuseum has reached a settlement with the heirs of Richard Semmel on a painting by Camille Pissarro that the Jewish collector was forced to sell in 1933 after fleeing Nazi Germany.

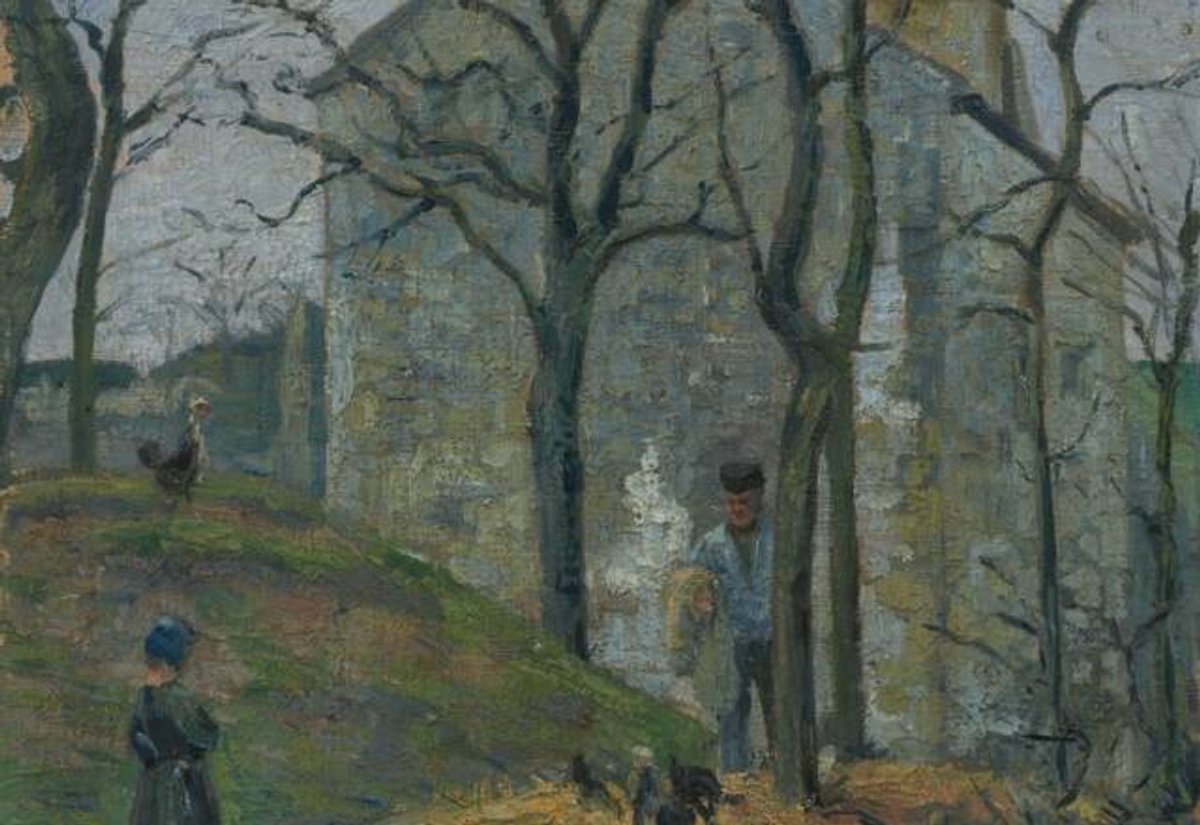

The museum said it agreed to pay a sum “close to the market value” of the painting. La Maison Rondest, l’Hermitage, Pontoise, painted in 1875, was donated to the Kunstmuseum shortly before its 2021 Pissarro exhibition by Klaus von Berlepsch, a local collector. Its provenance was not at the time immediately clear and the collector, who has since died, was unaware of the painting’s history, the museum said in a press release.

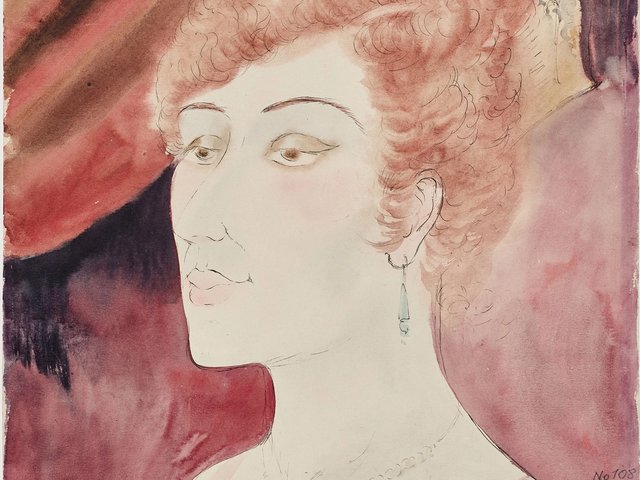

The owner and manager of a successful textiles factory in Berlin, Semmel faced Nazi repression for both his Jewishness and his politics in spring 1933. He fled with his wife, Claire Semmel, to the Netherlands in June that year. He managed to take most of his collection with him. The contents of his Berlin villa, including the art left behind, were seized and pawned and in 1934, he sold the house to pay taxes in Germany. He continued trying to save his struggling company until 1935.

In 1939, a year before the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands, the couple fled via Chile to New York, where they lived in poverty. After his wife’s death, Semmel was cared for by a friend he knew from Berlin, Grete Gross. In gratitude, he made her the sole beneficiary of his will when he died in 1950; the current heirs are her granddaughters.

Semmel offered the Pissarro painting at an auction in Amsterdam in June 1933, where it was probably not sold, the Kunstmuseum said. Later that year, it was on sale at a Basel gallery where it was bought by von Berlepsch’s father-in-law.

The Kunstmuseum Basel said it makes a distinction between Nazi looting and cases of “Fluchtgut” – instances where a Jewish collector sold work outside Nazi-occupied territory after fleeing. “There need to be very specific reasons to justify a restitution,” the Kunstmuseum said.

In this case, Richard Semmel “tried to keep his textiles company afloat with the revenue from the sales of his pictures,” the museum said. “The revenue from the sales of pictures went directly to the German Reich…For this reason, the Kunstmuseum and its commission take the view that the heirs’ claim is justified.”

Olaf Ossmann, the Swiss lawyer representing the heirs, said: “We agree with the decision, but we don’t agree with the reasoning.” Ossmann was involved in drafting a series of international “best practices” published this year to reinforce the non-binding 1998 Washington Principles and clarify ambiguities in them that have led to disputes. Switzerland is among the 27 countries that have so far endorsed the new guidelines.

The best practices state that “taking into account the specific historical and legal circumstances in each case, the sale of art and cultural property by a persecuted person during the Holocaust era between 1933-45 can be considered equivalent to an involuntary transfer of property based on the circumstances of the sale.”