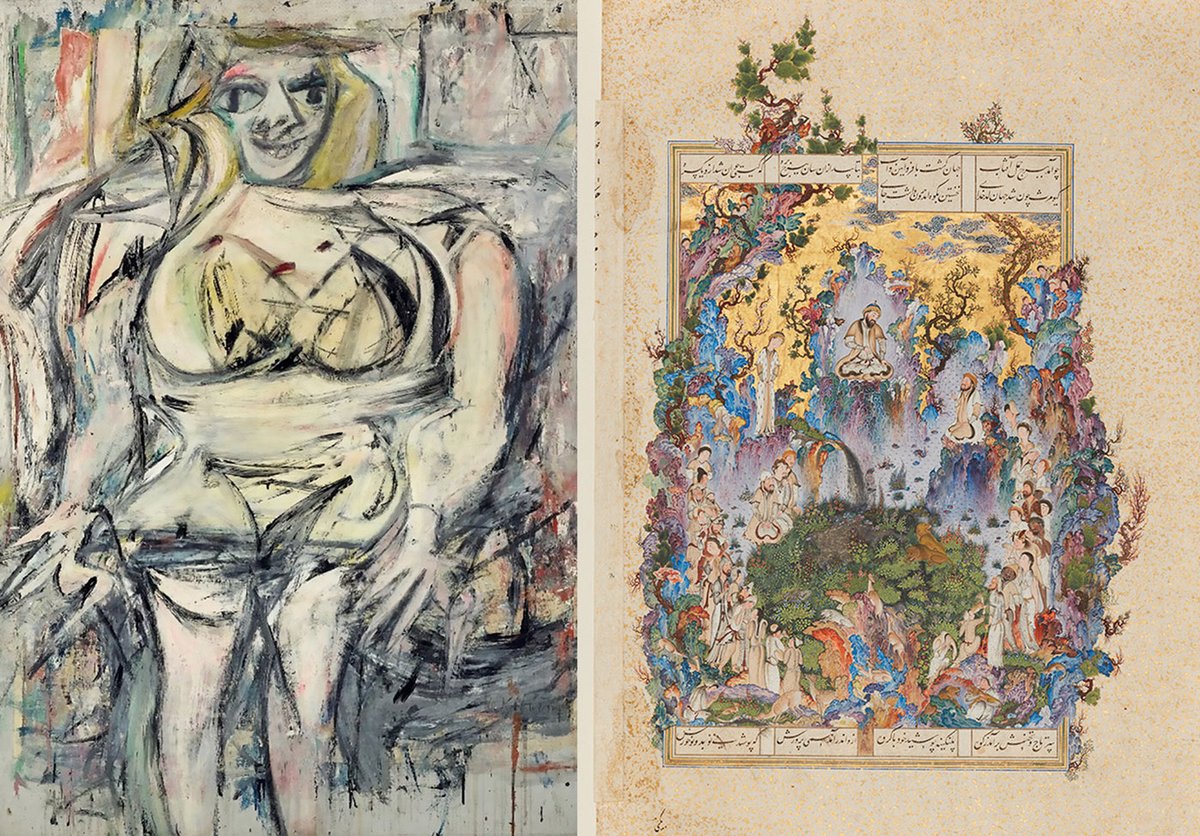

On 28 July 1994, on the tarmac of Vienna airport, Oliver Hoare, a British art dealer, delivered a number of wooden crates to officials of the Islamic Republic of Iran. They contained the text, binding and 118 miniature paintings from Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnameh, a 16th-century Persian manuscript and one of the wonders of Islamic art. The Iranians handed over Woman III, a 1953 nude by the US Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning, before flying home with the parts of the Shahnameh. Hoare considered this deal a “miracle”; his posthumous memoir The Exchange (2024) is the story of how he pulled it off.

As a young man, Hoare set off overland to Iran, and spent the rest of his life, in one way or another, on that golden road, dealing and travelling. This book, his son the gallerist Tristan Hoare tells The Art Newspaper, was born of “a deep personal connection to the culture and a love of its art”.

It paints a familiar picture of pre-revolutionary Iran. There are chic cocktail parties and Timurid caravanserais, fragrant gardens and powerful stereos, wily bazaar merchants and “doe-eyed beauties”. There is also a meeting with Farah Pahlavi, the wife of Iran’s then ruler and a prolific patron of the arts. Pahlavi used the country’s oil wealth to buy Modern art and, in 1977, inaugurated the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in a Modernist building in the city’s leafy northern suburbs, surrounded by a sculpture park packed with Henry Moore sculptures.

The museum’s collection remains, to this day, one of the most significant outside the West, reading like a roll call of the 20th century’s most famous artists: there are works galore by Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko and Amedeo Modigliani, to name but a few.

Consigned to cellars

But after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, some of these pictures were seen as offensive by the country’s new clerical rulers. Consequently, scores of paintings like Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Gabrielle with Open Blouse (1907) were consigned to the museum’s cellars, where they have languished ever since. In the meantime, the market for Modern art has skyrocketed, making the basement of the Tehran Museum one of the highest-value storage units anywhere in the world.

The Iranian authorities will not show the paintings, but they will not sell them either. Originally unwilling to flog the country’s assets, Iran can now neither sell the pictures, because of banking sanctions, nor keep them in good repair. Woman III is the only work to have left the collection, and, in return, Iran got hold of something uniquely important.

Oliver Hoare as a young man in Iran Photo: The Exchange; 2024 supplied by Damian hoare

The Shahnameh, composed at the turn of the 11th century by the poet Ferdowsi, is a foundational artefact of Persian culture. Its narrative mixes myth and history, with a colourful cast of heroes, creatures and villains, whose travails are tenderly explicated in Ferdowsi’s high-flown Persian idiom.

For 1,000 years, the poem was recited and passed around the Persianate world in books of hand-copied verse interspersed with colourful illustrations, from the Balkans to Bengal. But none of these manuscripts surpassed in quality the one constructed for the 16th-century Iranian ruler Shah Tahmasp. While Michelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel, the Shah’s workshop—binders, gilders, calligraphers and painters—took 20 years to complete the Shahnameh. On 258 gilt-specked pages, slightly larger than A4, delicate figures radiate in dream-like landscapes, endlessly varied in tone and style. The late scholar and collector Stuart Cary Welch called it an “art gallery in miniature”; it is the best, most extensive example of its genre.

Dismembered and dispersed

But the Shah lost interest, and in 1568 he gifted the manuscript to the Ottoman Sultan Selim II, to seal a peace deal, while some of its artists migrated to the Mughal court, shaping the subsequent course of Indian painting. Meanwhile, Tahmasp’s Shahnameh passed through a series of owners until in 1959 it was bought for $350,000 by the American industrialist and bibliophile Arthur Houghton Jr. Houghton then controversially dismembered the manuscript and dispersed 140 of its folios among museums and collectors.

For 400 years, its miniature paintings had drawn meaning from each other and from the intervening text, amounting, as Hoare recognises, to “more” than the sum of its parts. But with the loss of unity, its form and character as a work of art was fundamentally altered.

Persian miniature painting was a courtly affair, designed for the eyes and fingers of a tiny elite audience, intended for lavish albums, not for display on walls. Some have seen Houghton’s dispersion of his Shahnameh as an act of cultural vandalism; others as the inevitable concomitant of market forces. But while it undoubtedly hinders certain avenues of study, it also enables it to be appreciated more widely, including, thanks to Oliver Hoare, in Tehran.

Different value systems

The Exchange describes the gripping chain of events that led to the repatriation of the remaining folios of the Shahnameh, in return for the single de Kooning. But that exchange has not been free of criticism; the former empress, for instance, charges Hoare with disrupting the unity of her collection. And no one can quite agree which side got a better deal; Woman III sold in 2006 for $137.5m, while, in 2011, just one leaf of the Shahnameh sold for $12m.

As Roxane Zand, the former Sotheby’s deputy chair for the Middle East and a former assistant curator at the Tehran Museum, explains, this involves two fundamentally different systems of value: “It is not particular to Iran, the question of how you compare the value of cultural heritage with financial value in the contemporary art scene.” Hoare has an answer: “Each miniature of that manuscript has a status in the cultural history of the world that no painting by the likes of de Kooning will ever deserve.”

• Oliver Hoare, The Exchange: Shahnameh/de Kooning, LG Press, 204pp, £25