You won’t have seen any of these dealerships at Frieze London or Art Basel Paris. You won’t read about their exhibitions in ArtReview or The Guardian. You might not be able to name any of their artists. But if you live in a reasonably prosperous town or city in a wealthy country like the UK, it’s more than likely that there is a retail outlet like this not so far from you.

What we might call a “high street” contemporary gallery is fairly easy to spot. They usually have an eye-catching picture in their street-level window, perhaps by a famous artist or celebrity; a bright white showroom filled with colourful paintings and prints, often with a vague street art vibe; friendly staff; and labels that usually have prices, sometimes written in biro pen.

Hefty turnovers

The more rarefied, upper echelons of the international art trade might regard businesses like Halcyon Gallery or Clarendon Fine Art as a less serious sector of the market. But, as recent filings with the UK’s Companies House database reveal, these multi-outlet operations that appeal to a broader pool of consumers are turning over serious amounts of money—far in excess of the takings of many of London’s most critically acclaimed galleries.

Moreover, those Companies House filings indicate that at a time when the demand at many high-end international dealerships has contracted, sales at these more commercial outlets have continued to grow (though it should be pointed out that 2024 accounts have yet to be released). Maybe the more “serious” end of the contemporary art trade has something to learn from these more down-to-earth business models.

Outpacing Pace

With spaces in prestigious neighbourhoods such as New Bond Street in London, the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris and Madison Avenue in New York, as well as further international locations in Monaco, Dubai and Singapore, Opera Gallery seems more geared towards the high-end luxury market than the high street. But, as the company’s London-based chief executive, Isabelle de La Bruyère, points out, Opera Gallery has for 30 years maintained a loyal client base through its “transparent, open door approach”. She says the dealership’s French founder and owner, Gilles Dyan, has always recognised the importance of having ground floor galleries that encourage passers-by to enter.

La Bruyère, who was formerly the head of client advisory at Christie’s in London, adds: “It doesn’t matter if they’re here to buy, or just to look. It’s about nurturing the curiosity of people. Our founder also believed it’s important to be near luxury markets. We share a lot of their clients. Shoppers are important.”

Last year, Opera Gallery achieved global sales of €147.5m (around £127m at 2023 exchange rates), a 10% increase on the previous year, according to Companies House. Over the same period the powerhouse international mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth turned over £143.9m, a 16% decrease on its 2022 results. Pace’s sales declined slightly to $104.9m (equivalent to £80.6m at the time of publication). Comparable data for Gagosian and White Cube, the art market’s other largest dealerships, is not available.

Like high street contemporary galleries, Opera combines more expensive works by famous names—in its case, oil paintings by post-war Francophile favourites, such as Jean Dubuffet, Jean-Paul Riopelle and Pierre Soulages, costing millions—with impactful images by lesser-known living artists at more approachable price levels. During London Frieze Week last month, Opera showed works by the Brazilian figurative painter Gustavo Nazareno, inspired by his country’s Black diaspora, priced between £9,000 to £60,000.

Quantity vs quality

Critics might say that UK-based group galleries like Clarendon Fine Art and Halcyon are about quantity rather than quality. Clarendon has more than 80 retail outlets, including 13 on cruise ships; Halcyon, which has a gallery in Harrods and owns the Castle Fine Art chain, counts more than 40. But these businesses’ sales figures are undeniably impressive by art world standards.

Last year Clarendon and Halcyon both turned over almost £95m, with sales respectively 17% and 15% up on 2022, according to Companies House filings (Clarendon’s latest filing, it should be noted, only accounts for January to July 2023). By comparison, Lisson and Sadie Coles galleries respectively took £49.9m and £51.7m in 2023, down 33% and 18% on the previous year.

“When I first entered the art world 30 years ago, I was struck by the exclusivity and elitism that permeated the galleries I visited,” says Clarendon’s chief executive, Helen Swaby. “It was an environment that felt intimidating rather than welcoming. I was determined to create something different.”

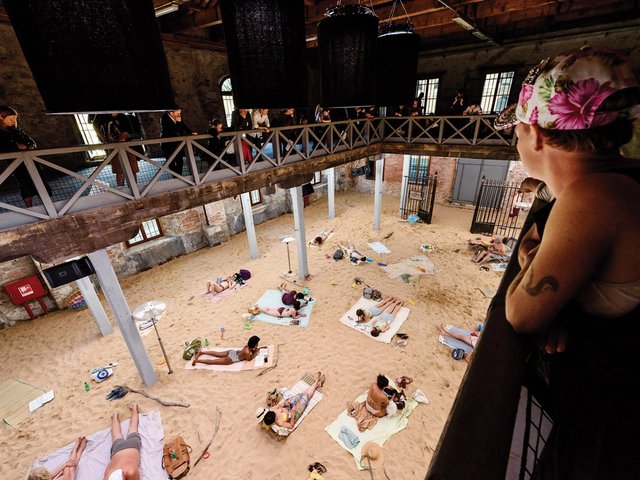

Change can be sensed at some of those major-name galleries, which are now diversifying into retail and lifestyle in an effort to expand their reach. Conversely, there are moments when high street galleries intersect with the elite art world. Halcyon represents the Italian artist Lorenzo Quinn, whose theatrical, super-size figurative sculptures have made dramatic interventions in Venice during recent Biennales. Tongue-in-cheek paintings and prints by the pseudonymous Connor Brothers duo, who are represented by Clarendon and Maddox Gallery, are regularly resold at Sotheby’s and Phillips auctions. The Connors’ 2020 spoof painting of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi, titled The Bestest and Most Expensivist Painting in The History of Art, showing the Saviour holding a lit cigarette and an ashtray, sold for £44,100 (with fees) at Sotheby’s in 2021.

‘Spaces where you’re not made to feel silly’

“The idea that if something is expensive, it’s good, has been held up by the official art world,” says Mike Snelle, the former street art dealer who is one half of the Connor Brothers (James Golding being the other). “Whereas I don’t think those two things align always, or even often.”

Snelle says the Connor Brothers sell around 40 to 50 paintings a year, priced between £30,000 to £35,000 each, plus limited-edition prints that generally cost between £1,000 to £3,000 each. “They’re buying them because they like them, not because they know other people who are buying incomprehensible art that costs a lot,” Snelle adds, discerning two distinct approaches to the business of making and selling art. “One is expensive and for very few people. The other has broader reach and is very accessible. It creates welcoming spaces where you’re not made to feel silly and uneducated about what you’re seeing.”

This is the world of high street art, an art world uncluttered by critics, curators, advisers, investors and speculators. Of course, the question of whether the art on show represents true value for money remains. But that question is as relevant here as it is at Gagosian or its similarly unapproachable peers. At least people are engaging with, and sometimes even buying, art they like.

“Anyone who spends £1,000 on a picture deserves to be taken seriously,” Snelle says. As sales at the upper, elite end of the market continue to stutter, all those trying to make a living out of selling art might do well to bear that in mind.