After Otto Kallir opened Galerie St Etienne in 1939 on West 57th Street in New York, having fled his birthplace of Vienna then under Nazi occupation, the Jewish art historian and dealer became instrumental in introducing US museums and collectors to the work of Austrian Expressionists including Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, Alfred Kubin and Oskar Kokoschka.

“Most of the Austrian works he brought out had no market and no value at that time,” says his granddaughter Jane Kallir, who co-directed the gallery after Otto’s death in 1978 until closing its exhibition space in 2021. She now leads the Kallir Research Institute (KRI), which continues and expands on her grandfather’s scholarship.

This month, the KRI, a non-profit foundation established in 2017, is hanging out its shingle at 156 West 56th Street in new spacious, purpose-built quarters. Its vast library and archives—pertaining to the Austrian and German Modernists stewarded by Galerie St Etienne for decades as well as self-taught artists, including Grandma Moses, whom Otto championed beginning in 1940—are open to researchers by appointment.

The KRI contributed source materials and money to the making of the new documentary Transatlantic Tastemaker: Otto Kallir & Austrian Modernism, produced by the Austrian Television Network in German and English, which premièred last month in Austria. It marks the 100th anniversary last year of the art dealer’s founding of the original Neue Galerie in Vienna—the prototype and namesake of the museum established in New York by Ronald Lauder in 2001 dedicated to early 20th century Austrian and German art.

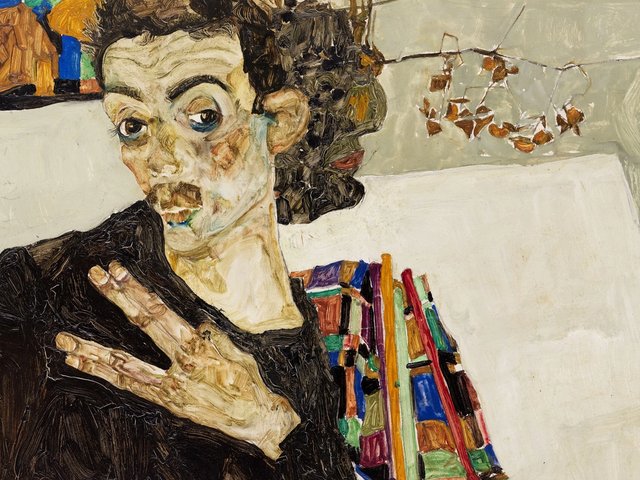

Next year the KRI plans to launch phase two of the digitised Egon Schiele catalogue raisonné, originally initiated by Otto in 1930 with the documentation of Schiele’s roughly 300 paintings. After joining the gallery fresh out of university, Jane Kallir volunteered to tackle Schiele’s 3,000-odd drawings and watercolours. “I had no idea what I was getting into, but it really became a life’s work,” she says. Kallir published the first comprehensive catalogue raisonné of these works in 1990 and has continued to update it as more works have been authenticated—another primary activity of the KRI.

“There is no question that Schiele is one of the greatest draughtsmen of all time,” says Kallir, who estimates people contact the research centre about once a week with a potential Schiele. She works with curators from the leading museums in Vienna to evaluate works, most of which prove to be fakes. “People love their fakes and have ego invested in their authenticity in a way that they often don’t with a work that’s pre-certified.” Kallir is a co-curator of Changing Times: Egon Schiele’s Last Years, 1914-1918, opening in March 2025 at the Leopold Museum in Vienna.

Kallir declined to comment directly about ongoing litigation surrounding Schiele’s 1916 drawing Russian War Prisoner, acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1966 and once owned by Fritz Grünbaum, who was arrested by the Nazis in Vienna in 1938 and died in a concentration camp. Grünbaum’s heirs say the drawing was looted by the Nazis while the museum maintains the work passed on to Grünbaum’s sister-in-law, who sold it after the war to a Swiss dealer. (The drawing is known to have changed hands in 1956 through Galerie St Etienne, casting a shadow on Otto.) A ruling in the case is expected in January.

Restitution efforts

“My grandfather, after the war, made huge efforts to help people get their stuff back,” says Kallir. She turned over crucial information from his files to The New York Times in 1997 when Schiele’s 1912 painting Portrait of Wally Neuzil was on loan to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York from the Leopold Museum, which ultimately compensated the heirs of Lea Bondi Jaray, whom it was proven had given up the painting under duress in 1939. “I have been proactive in advocating for just restitution when there’s proof of theft and accurate documentation of provenance.”

Otto Kallir with Grandma Moses, the self-taught artist whom the gallerist championed. The institute is now placing her works in US museums’ collections

© Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York

Kallir has begun a process of placing core works from her family’s holdings with museums. Earlier this year, through a combination of gift and sale, a dozen drawings and unique working proofs by Käthe Kollwitz went to MoMA, half of which were in the museum’s major Kollwitz exhibition that opened in March.

Kallir has reserved around 100 Grandma Moses paintings for institutions—50 of which, collectively valued at around $5m, have now been allocated to five museums. Thirty of these paintings are going to the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, DC, which will also receive Moses source material and drawings for a future study centre there. Kallir is collaborating with the museum on a Moses retrospective opening at the SAAM next October.

Smaller groupings of Moses paintings are earmarked for Bennington College in Vermont (near Eagle Bridge, where the artist lived), the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and the forthcoming Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles. Kallir is considering other institutions that might receive the remaining Moses works as well as the family’s substantial collection of Austrian and German works.

Over the next five years, she says, “one of my goals is basically to give away my family’s collection”.