Last April, the French president, Emmanuel Macron, called for the creation of a “cultural pass” for young people across Europe. “The cultural pass does extremely well in France. Germany has just adopted it! What if all young Europeans could benefit from it?,” Macron said last October.

In 2015, Matteo Renzi, the then Italian prime minister, was the first European politician to launch a “Bonus Cultura” following Islamic State’s destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East. Under the scheme, all Italian 18-year-olds could receive €500 to spend on a cultural product or activity. Nearly two-thirds (60%) of eligible young people signed up, but, just before the deadline, only 6% had found a way to spend the money. The Bonus Cultura website did not work properly, and most Italian towns have no theatre, concert hall, cinema or bookshop in which to use the pass. Cultural venues were reluctant to sign up fearing the burden of paperwork and delays to getting payment from the state. The programme was also overshadowed by a prolific black market, with recipients trading their funds for mobile phones, computers or cash. In 2024, the current prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, downsized the programme to a “merit card” for top academic students and a “culture card” for low-income families.

France leads the way

Despite these problems, other countries followed suit. Last year, 326,000 Spanish 18-year-olds (65% of that age group) signed up for a Bono Cultural Joven of €400. Germany has been thriftier: the KulturPass was launched last year with a grant of €200, but this has already been cut to €100.

No country has taken the idea as far as France, however. The Pass Culture was Macron’s only culture policy proposal when he was elected in 2017. After a period of experimentation, the pass was extended to all young people aged between 15 and 18, with grants ranging from €20 to €300. The cost ballooned to €260m per year, including €50m for group activities in schools. It became the culture ministry’s highest expense, amounting to double the public support provided to the Musée du Louvre.

At 18 it’s too late to discover cultural activities like museums, classical concerts or operaChristian Bilhac, French senator

However, just one month after the president’s call to extend the initiative across Europe, the culture ministry’s auditing body concluded a startling report on the impact of the individual Pass Culture. The report was published in September. “It is impossible to show that the programme has fulfilled its mission of public service by enlarging and diversifying cultural practices” for young generations, the auditors wrote.

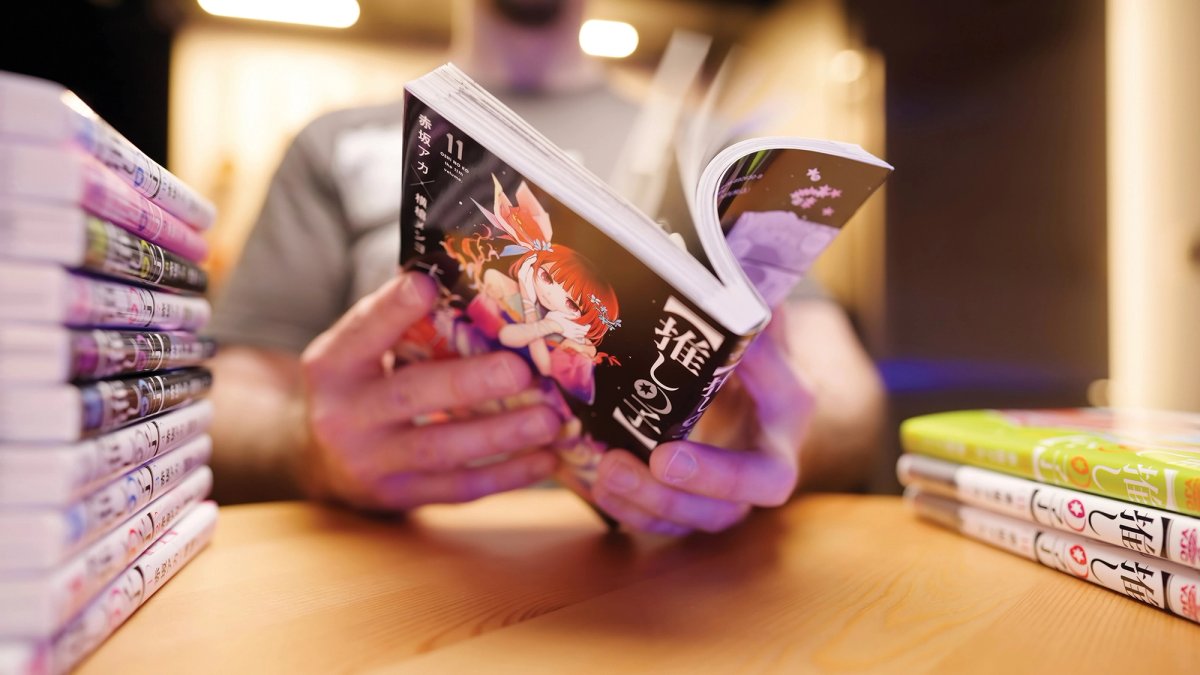

According to the report, 80% of 18-year-olds have benefited from the pass. In two-and-a-half years, 71% of the 24 million users have bought books, with half of those buying Mangas and comics. As a result, France has become a leading consumer of Mangas, second only to Japan, with 40 million copies sold last year. Fifteen percent is spent on cinema tickets, while only 2.8% of the funds pay for concert seats (of all sorts), 0.7% goes towards buying a museum card and a tiny 0.01% for theatre tickets.

Overall, the system mainly benefits teenagers from educated and wealthy families, who already have access to comic books and movies. This study contrasts with reports of the success of the “group pass”, which helps teachers organise cultural outings and activities with their classes.

There are now calls to scrap the initiative and fund art education in schools instead. A senatorial commission has also criticised the highly dysfunctional system: “The later you plant seeds the less you harvest. At 18 it’s too late to discover cultural activities like museums, classical concerts or opera,” Senator Christian Bilhac said.

Rachida Dati, the outgoing culture minister, has admitted that the platform needs “fundamental reform” and initiated a preliminary series of corrections.

It remains to be seen whether the programme will survive the budget cuts expected from the new government.