The colonial photographic lens has promoted the widely spread idea within the Western psyche of Africans as primitive beings and a subject for ethnographic studies. It bolstered racist tropes and encouraged the invasion of Africa, disguised behind the “civilising” mission. Colonial photography and moving images were not only used to dehumanise and “other” African people but were also a tool to document land transformation, migration and settlement for colonial propaganda. Yet despite the agenda to subjugate Africans, contact with the camera led the colonised to use it as a means to reclaim their autonomy and create their own aesthetic practice: liberating themselves from the Western imagination.

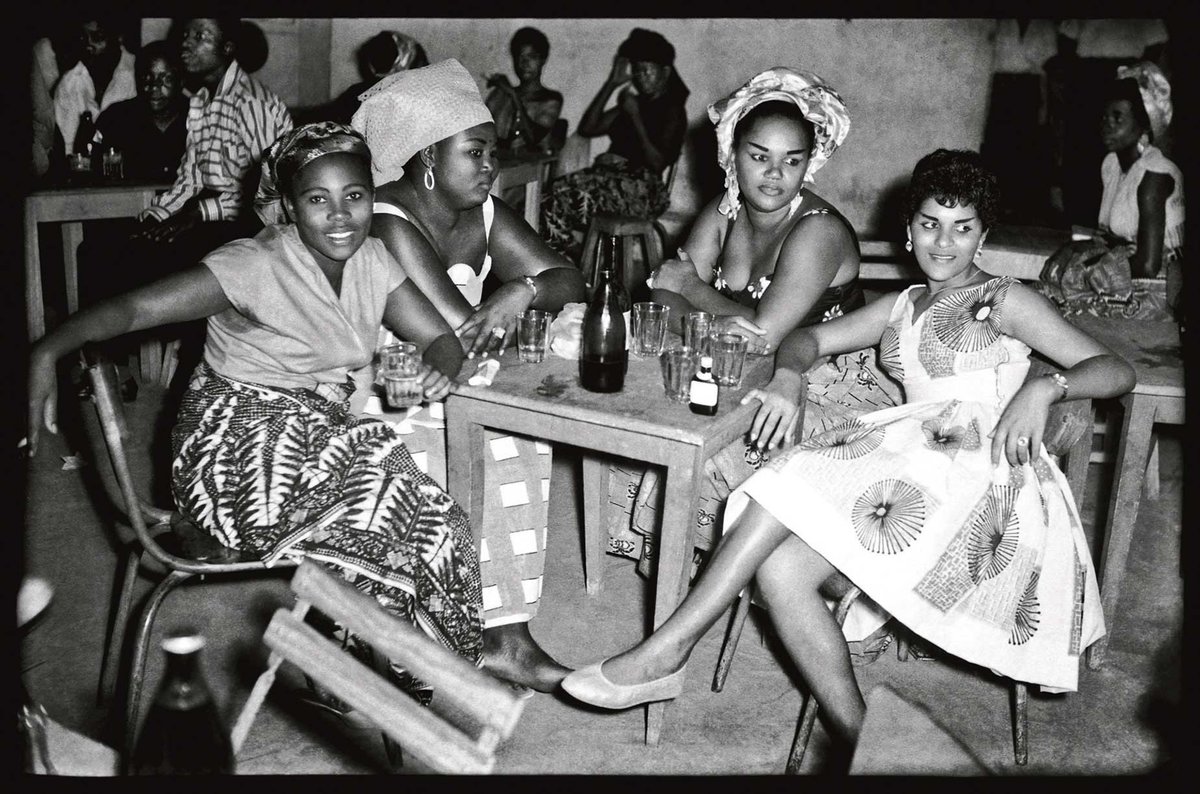

In the late 19th and 20th centuries, African visual artists began to reinvent and reinterpret ways of seeing and creating new forms of expression through the African gaze. The evolution of photography in the continent became noticeable with studio portraiture. African photographers travelled across different regions, setting up temporary and then permanent studios. They developed a rich aesthetic, from family snapshots to self-portraits against luscious backdrops, and capturing moments of leisure and joyous scenes.

The spirit of optimism in post-colonial Africa is encapsulated by pioneers such as the Malian photographer Malick Sidibé (1935-2016), who gave his sitters the space to express themselves however they wanted, away from the austere and strict rules of past portraiture, and the Cameroonian-Nigerian photographer Samuel Fosso (born 1962) with his theatrical and fashionable images, where the sitters radiate confidence. At the same time film provided the opportunity for world-building and liberation, becoming a force for change during the upheavals of the decolonisation of Africa that spanned the period from the 1950s to 1975.

In her debut book, Amy Sall, writer, researcher and collector-archivist, aims to “provide a balanced overview of the cultural, political and aesthetic contributions made by a number of pioneering figures across photography and cinema”. The African Gaze is not intended as a complete survey but, rather, one that scratches the surface of African visual culture to act as an introduction for audiences both familiar and new to African cinema and photography. As an entryway for self-study, it invites audiences to go on their own journey of exploration and research, beyond the names featured.

In addition to Sall’s preface, there are written contributions from the historian Mamadou Diouf, and the writer-scholars Zoé Samudzi and Yasmina Price, which provide an overview of the key themes of colonial history, identity, autonomy and liberation politics. It is not often that both mediums are combined in such an insightful manner, alongside engaging source material that encourages the reader to explore the subject area further. There are also compelling interviews with the Malian film director Souleymane Cissé (born 1940) and Fosso.

Split into two sections—25 photographers and 25 film-makers, both well-known and lesser-known names—each of the image-makers, who include Jean Depara, Lazhar Mansouri, Ernest Cole, Moustapha Alassane, Sarah Maldoror and Ousmane Sembène, has their story summarised in individual biographical entries (with extra information placed in footnotes) accompanied by stunning images of their works and archival visuals that serve as cultural markers.

Pan-African principles

With an emphasis on pan-African principles, Sall tried as much as possible to source archival imagery, interviews and documents directly from the image-makers who are alive, or through their families and personal estates. She wanted them to be part of the process and to showcase images that have not been widely exhibited or seen. The book came about, Sall writes in the preface, from her popular academic course for The New School, New York, “The African Gaze: Visual Culture of Postcolonial Africa and the Social Imagination”, which sprang from a combination of her background in human rights and cultural studies (she holds an MA from Columbia University) “with a passion for African artistic and cultural production”.

There are—indeed, have been—many women practitioners across the continent, although only a few are represented in The African Gaze. As Sall explains, at present there is not “sufficient scholarship or visual material” for their stories to be told. This reiterates the importance of archival work as a means of memory-making. Felicia Ewuraesi Abban (1936/7-2024), included here, is considered Ghana’s first professional woman photographer, and her ground-breaking career in a male-dominated and controlled industry spanned 60 years. She was also a sharp businesswoman who understood how to advertise her practice, promote her studio and gain clientele. She even worked with Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president, becoming his photographer during the 1960s.

With comprehensive and popular exhibitions such as In the Black Fantastic (2022, Hayward Gallery, London), Black Venus (2023, Somerset House, London), A World In Common (2023-24, Tate Modern) and more, there is a shift in the cultural sphere, as more people become interested in the works of artists from the African diaspora, which gain international recognition in the process—and about time, too.

Ultimately, The African Gaze is a collaborative book that is a testament to the power of recording visual histories. It features figures whose names will be remembered through current and future generations. “It is also a token of gratitude,” Sall says, “to the pioneering image-makers—both within these pages and outside—for their vision, foresight, passion and vigour. I am endlessly indebted to them”.

• Amy Sall, The African Gaze: Photography, Cinema and Power, Thames & Hudson, 288pp, 280 illustrations, £45/$65 (hb), published 25 July/17 September

• Emi Eleode is a journalist and writer on arts and culture, with an emphasis on current affairs and social issues, for publications including ARTnews, The Guardian and Wallpaper*