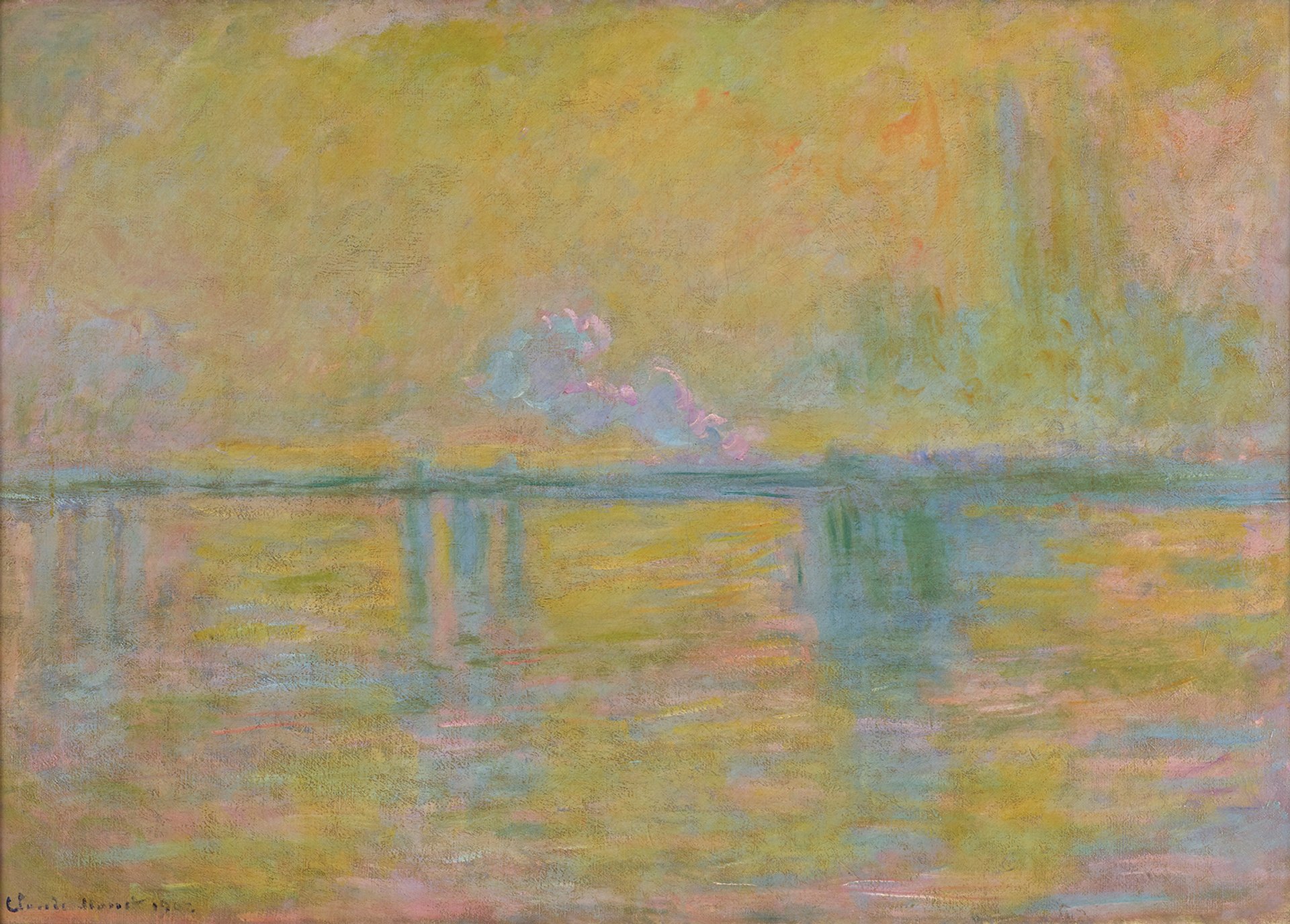

Winston Churchill’s penchant for chain smoking cigars no doubt contributed to the build-up of grime on a Claude Monet riverscape in his sitting room. The painting, depicting London’s Charing Cross Bridge, has been conserved by the National Trust, which owns Chartwell, the statesman’s home in the Kent countryside. The newly restored Charing Cross Bridge is being unveiled in the Courtauld Gallery’s ambitious exhibition Monet and London: Views of the Thames (27 September-19 January 2025). On display will be 21 of Monet’s London scenes.

Charing Cross Bridge before conservation work removed grime caused in part by Churchill’s ten-a-day cigar habit Photo: Matthew Hollow; © National Trust Images

Although Monet signed and dated the painting 1902, he actually began it on a visit to London in the autumn of 1899 or early 1900. However, an important discovery is that it was finally completed in 1923, when he sold it. His main change was the addition of swathes of yellow to the reflections in the water and areas of sky, representing as much as a third of the canvas. This yellow gradually became much less visible because of the accumulation of airborne dirt and a darkening of the varnish. Rebecca Hellen, the National Trust conservator, points out that along with sooty grime deposited from fireplaces, people smoking would have “contributed to the surface dirt”.

Churchill, who lived at Chartwell for 40 years, typically smoked ten large Cuban cigars a day. He stored nearly 4,000 cigars in a small room off his study. In photographs he is very often depicted smoking and a cigar almost became his personal emblem.

Monet worked on the painting from a balcony on an upper floor of the Savoy Hotel, where he was staying. This looked down on the 1864 bridge and the more distant Houses of Parliament. The artist was struck by London’s distinctive yellow haze. In 1901 he had written to his wife, Alice, remarking on the “extraordinary fog so very yellow”. This was largely caused by sulphurous emissions from burning coal. Although Monet created his composition of Charing Cross Bridge in 1899-1900, he made adjustments to it in 1902, at his studio at Giverny. There the picture remained until he sold it in 1923 (three years before his death). In those years he reworked it substantially, strengthening the yellow haze. He also moved the towers of the Houses of Parliament from their actual position on the far right to slightly closer to the centre of the scene, making them more visible.

The National Trust conservator Rebecca Hellen with the restored Charing Cross Bridge. (When this photograph was taken, the lower left corner of the painting had not yet been cleaned.) Photo: © The Art Newspaper

After going to a Parisian dealer, Charing Cross Bridge was bought by the pharmaceutical entrepreneur Henri-Edmond Cannone. It was sold in 1942 and purchased by the American literary agent Emery Reves in 1949. Reves, who worked for Churchill, acquired the Monet specifically to give to his client, who was then the Leader of the Opposition in parliament.

The story behind this extraordinary gift was revealed by The Art Newspaper in 2007. On 23 December 1949 Reves wrote to Churchill: “Knowing that Monet is your favourite painter I have been searching for one of his good paintings for many months… Please accept it as a very small token of my gratitude for your friendship.”

Reves ended his letter: “My very best wishes for a happy 1950 during which I hope you will dissipate the fog that shrouds Westminster.” In 1945 Churchill had lost his position as prime minister to the Labour leader Clement Attlee, with the war statesman again becoming prime minister in 1951. A note in Churchill’s engagement diary reveals that he invited Reves for lunch on 26 December, three days after the letter.

Floating ‘in sparkling air’

Churchill, himself a talented amateur artist, must have been thrilled with Charing Cross Bridge, which even included his beloved Houses of Parliament. In 1935 he made a copy of a Monet seascape of the Normandy coast; later, in his 1948 book Painting as a Pastime, he singled out the work of Monet and three other French artists as floating “in sparkling air”.

Nowadays the gift of a Monet to an MP would need to be declared in the parliamentary Register of Members’ Financial Interests (and would certainly set off a media storm), but such matters were then regarded as private. During his lifetime, Churchill’s Monet remained a secret known only to those close to him. His ownership was not even recorded in the comprehensive 1985 Wildenstein catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work.

Charing Cross Bridge, now on show at the Courtauld, usually hangs in its original position in the drawing room at Chartwell, now run by the National Trust Photo: Andreas von Einsiedel; © National Trust Images

Churchill hung Charing Cross Bridge in Chartwell’s drawing room, the heart of the family home. There, he would relax after a hard day’s political and literary work, usually with a cigar in hand. After his death in 1965 Chartwell and its contents passed to the National Trust. The Monet has always remained on the same wall and, until the forthcoming Courtauld exhibition, it had never been lent.

Hellen, working in the National Trust’s Royal Oak Foundation Conservation Studio at Knole, has now finished her task. When we visited the studio in August virtually all the painting had already been cleaned, temporarily leaving a patch of discoloured non-original varnish replete with trapped dirt in the lower-left corner.

Hellen’s aim has been to bring back the painted surface to “how it would have been left by Monet” when the painting was bought from his Giverny studio in 1923. She decided against retouching the paint losses, which are minor.

Conservation of the frame has also just been completed. The gilded frame is French, from the early 20th century, and was probably added by the dealer who bought the painting from Monet in 1923. It would have been regarded as quite a posh frame at the time, evidence of Monet’s growing status in the art trade.

It is not recorded how much Reves paid for Charing Cross Bridge, but two of Monet’s other London paintings were sold at Christie’s in 2022 for $65m and $76m: Waterloo Bridge, Veiled Sun (1903), now with a private collector; and The Houses of Parliament, Sunset (1903), now with Hasso Plattner and on loan to Museum Barberini in Potsdam. Both of these will be joining Churchill’s painting in the Courtauld show.

Karen Serres, the curator of the Courtauld’s exhibition, is delighted to have the Churchill painting on loan: “It is one of only two views of the Thames in a British public collection, the other coming from Museum Wales,” she says. “Its provenance and conservation treatment will make it a destination picture, for us and for Chartwell.”