Three employees at the Noguchi Museum in New York City have been fired for violating the museum’s new dress code policy for staff. The policy was updated last month and, among other dress deemed overtly political, banned employees from wearing keffiyehs, a traditional type of headdress often worn by men in North Africa and West Asia that has become heavily associated with pro-Palestinian sentiments, especially amid the war in Gaza. A fourth employee, the director of visitor services, was also terminated, however it is unclear if this was related to the dress code.

The firings come after an action on 21 August in which 14 staff members at the museum—nine of whom have public-facing roles—walked off the job in protest of the new employee dress code. This action followed the circulation of an internal petition that was signed by around two thirds of the museum's 72-person staff, calling for a reversal of the policy and alleging it is anti-Palestinian.

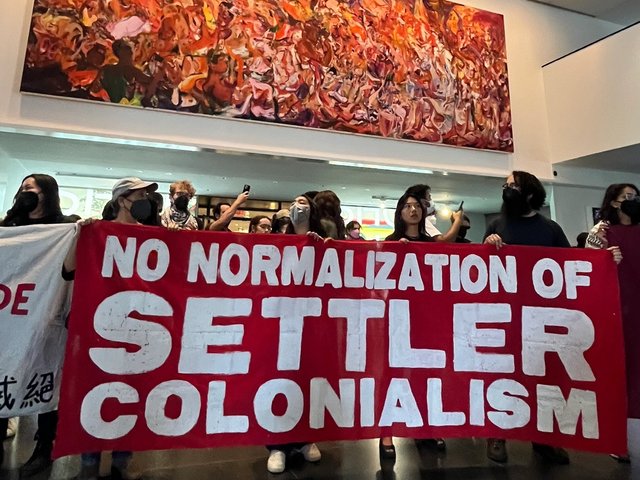

Following the firings, supporters protested outside the museum on 8 September. Those who came to show support included artists, cultural workers and local residents in the Astoria neighbourhood where the museum is located. Protesters also called on the museum’s director, Amy Hau, to step down. Participants handed out flyers highlighting the political significance of Isamu Noguchi’s work and providing information about the war in Gaza.

“I am astounded by the stupidity and the irony of a cultural institution banning a cultural garment. Leadership claims by banning the keffiyeh it is making them neutral,” Natalie Cappellini, one of the three fired employees, said in a speech at the 8 September rally. “When Amy Hau told us she was banning the keffiyeh she used the excuse that [the Noguchi Museum] is a sanctuary, a sanctuary away from politics. How naïve can you be?”

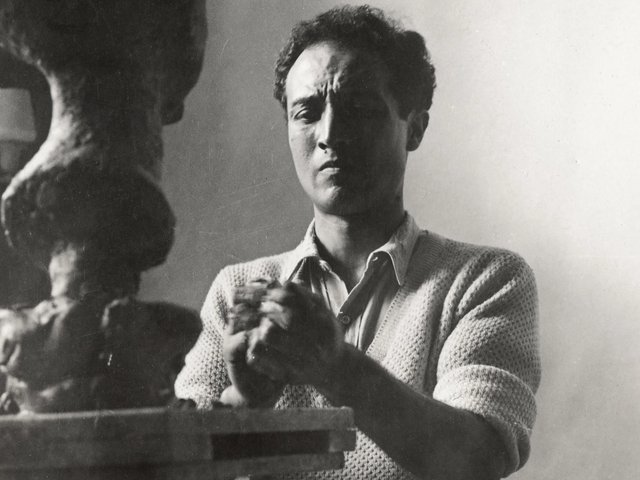

The museum’s namesake, a globally revered American artist of Japanese descent, was vehemently opposed to the Second World War. In 1942, in an act of solidarity against it, he voluntarily entered the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona, one of the prison camps built in western states following the bombing of Pearl Harbor to hold Japanese citizens and Japanese Americans. Noguchi had been a New York resident at the time, and thus was not forced into the camps. A 2018 exhibition at the museum chronicled the time he spent in the prison camp.

“Given this pertains to personnel matters, we are unable to provide further details,” a spokesperson for the museum tells The Art Newspaper. “While we understand that the intention behind wearing this garment was to express personal views, we recognise that such expressions can unintentionally alienate segments of our diverse visitorship. We discussed with staff that it is our duty as a public cultural institution to ensure that the museum is welcoming to all.” The spokesperson added: “To maintain this environment, we have made the decision to remove political statements from our workplace.”

The museum’s revised dress code policy states that in order to maintain a “neutral and professional environment employees are prohibited from wearing clothing or accessories that display political messages, slogans or symbols”. It goes on to state that this prohibition includes apparel or accessories that “promote political parties, candidates or ideological movements”.

“To be inside of a museum of a man who self-interned with his oppressed Japanese American brothers and sisters in the Second World War, a museum filled with sculptures dedicated to the memories of those killed by atomic weapons—how dare they say this place is a sanctuary away from politics,” Cappellini said at the rally.