Karin Hindsbo, the director of Tate Modern, wants the London gallery to become much bolder. “I want us to take real risks,” she declares in her interview with The Art Newspaper. “I am sure that occasionally we will fail, but if we don’t do that we will never change.”

Hindsbo warns that “if you have a fear tendency and feel a need to always reach a consensus”, then Tate Modern will ultimately suffer. “It is and should be a ground-breaking institution. We are still only 25. It is a young and rebellious age!”

Next May will be the 25th anniversary of Tate Modern, which has become the UK’s most popular museum (along with the British Museum). This year it is on course to attract five million visitors.

Accessioning shakeup

Hindsbo also has revolutionary ideas which could lead Tate Modern to modify the way it accessions or collects works, particularly with regard to certain works of Indigenous art. “Some of the works belong to their community”, she points out, so you “cannot have the same classical ownership structure”.

She adds: “It could be some kind of dual solution or contract with the community. You cannot make the same kind of contract with one individual or gallery.” Indigenous art could arrive at the museum on long-term loan from a community rather than being accessioned into Tate Modern’s ownership and becoming part of its permanent collection.

Hindsbo took over as director of Tate Modern in September 2023, following on from Frances Morris. She came from heading Norway’s National Museum, where she organised a building projectthat brought together four individual museums, with the new integrated museum of art, design and architecture opening in June 2022. Before that, the Danish-born Hindsbo was the director of the Kode Museums in Bergen.

The Art Newspaper: Is the art world more tolerant or less so than when Tate Modern opened nearly 25 years ago? When it comes to issues such as gender or Gaza, there are disturbing signs of increasing intolerance.

Karin Hindsbo: Progressiveness and conservatism go hand in hand—it’s a symbiosis. As an art institution, we have become much more tolerant in some areas. But there is also a lot of tension, which builds into intolerance. The fuse is quite short, much more so now. You can get death threats by being an artist or a public figure. There is a weird paradox: as tolerance has grown, fear also grows. People are now much more frightened than they were. And that is dangerous.

You see this in institutions. We need to do everything “perfect”. We discuss risk, but when it comes to it, we are really afraid of taking risk. At Tate Modern, I want us to take real risks. I am sure that occasionally we will fail, but if we don’t do that we will never change.

What does that mean in practice?

For instance, if we put on an exhibition that puts forward various views and we fail, then we need to learn from it.

We need to dare to have things a little rougher at times. We may not get it quite right, people may disagree with us. But how else can we move forward?

Do you say this at staff meetings?

I try. I try to move forward with ideas which are sometimes a little unpolished. That will take time, but it is important. And I need to challenge myself.

But when the Tate makes mistakes, it certainly gets noticed, doesn’t it?

Yes, if we make mistakes, they will become visible really quickly—and nobody will forget them. But if you have a fear tendency and feel a need to always reach a consensus, then in ten years Tate Modern will not be the same institution. It is and should be a ground-breaking institution.

If one gets too comfortable and stagnates, one can do that in some places, but it is not OK here. We are still only 25. It is a young and rebellious age!

You’ve now headed Tate Modern for almost a year. What changes are you introducing?

Over the past decade there has been a huge focus on inclusion and diversity, in terms of both the collection and the programme. That will continue, because there is still so much to be done. We will “play” with artistic genres. We will explore the participatory element in art and encourage creativity in our visitors.

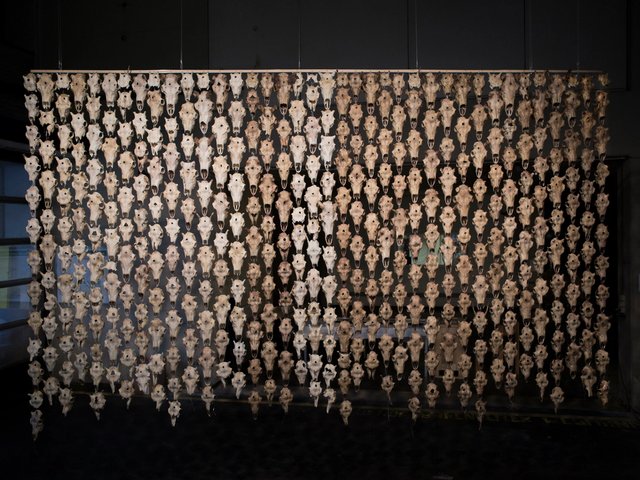

There will be a stronger focus on Indigenous artistic practices. For example, next year we will have a big show of Emily Kam Kngwarray, the Aboriginal Australian artist—from 10 July 2025 to 13 January 2026.

Can you tell us some more about your plans for Indigenous art?

The first of our initiatives will be on Sámi and Inuit art in Nordic Europe, an area I know well. There will be acquisitions and displays.

When we focus on Indigenous artistic practices, it is part of our wider effort to expand the canon of art history. It is about how we perceive art history, not just about adding works into the collection. We need to rethink the whole ownership structure of work by Indigenous artists.

Do you mean the Tate’s legal ownership?

Yes. When you work with Indigenous artists, some of the works belong to their community. So you cannot have the same classical ownership structure. Sometimes you need to think in new ways. You need to commit perhaps to loans of the works.

Do you mean that rather than acquiring works that are accessioned by the Tate you might borrow them from an Indigenous community?

Yes. For example, it could be some kind of dual solution or contract with the community. You cannot make the same kind of contract with one individual or gallery. It could be a long-term loan. With Indigenous practice, you need to think about the arrangements much more carefully. When we think about embedding Indigenous practice in the way we work at Tate Modern, it is not just about acquiring another loan for display; it is adapting the mindsets that follow from Indigenous practices.

What changes will you bring to the exhibition programme?

We will continue to strengthen transnational histories. We will revisit the concept of Modernism with Indigenous practices. For instance, in Nigerian Modernism (8 October 2025-spring 2026) we will show that there was Modernism outside of the Western canon in the 1960s.

We will also continue on the road to greater diversity, highlighting key female artists who have previously been seen as exotic reference points for well-known male artists.

Can you afford to mount ambitious exhibitions which involve international loans?

Transport is now very expensive and you have to think about sustainability. We need to collaborate in a different way. We will do big shows with other international partner museums or when we have something that is a strong point of departure in our own collection.

Should the new UK government increase its grant aid for the Tate?

It is easy for me just to say yes, the more the better. We are obviously in a financial pickle, as is everyone else. But the government needs to look at the whole sector, to make sure that we are not losing something valuable. For example, Camden Art Centre recently got a severe cut in their Arts Council grant. So the government needs to look at the bigger picture.

Tate Modern’s visitor numbers are only just behind those of the British Museum, the UK’s most popular museum. What is your target for this year?

We should be in reach of five million this year.

And 2025?

Possibly six million, or at least by the year after. Obviously we want as many as possible, but it is also important to get the right constellation of visitors. We will focus a lot more on gaining new members, rather than overseas tourists. That is a shift. We also want younger visitors—we are doing well with that, but want to do even better. We want diversity—for our visitors to represent our society.

What is the Tate doing to protect its art from damage by environmental protesters?

We have really good security measures in place. We do know when there is a heightened risk and we take precautions accordingly. That said, you are never 100% secure. As soon as you exhibit a work of art to the public there is always a risk.

On climate action, I completely understand why this is an important area. I do understand that activists want to draw attention to climate change and why it is an emergency. So I sympathise with the cause, not with the action taken.

If you target an artwork you do not have the knowledge of when you actually are making irreparable damage and when you are not. I cannot see how destroying art can help a cause, even though I sympathise with the cause.

Next May, Tate Modern marks the 25th anniversary of its opening. How will you be celebrating?

Emily Kam Kngwarray will be at the centre. There will be an amazing Hyundai commission in the Turbine Hall, which will put everything in perspective. And we will be highlighting 25 key works in our collection. On 12 May there will be a huge festival with music—free and open to all.