In the spring of 1970, Elizabeth Catlett, the American Mexican artist and activist, was forced to deliver her address to the Conference on the Functional Aspects of Black Art (Confaba) at Northwestern University in Illinois by phone after the US embassy in Mexico had labelled her “a threat to the wellbeing of the United States”, as she put it, and refused her visa application. “To the degree and in the proportion that the United States constitute a threat to Black people, to that degree and more, do I hope I have earned that honour,” she told her listeners at Confaba. “For I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be a Black revolutionary artist, and all that it implies.”

Catlett’s self-defining quotation serves as the title for a new survey of the artist, who died in 2012. The most comprehensive ever organised in the US, it opens this month at the Brooklyn Museum and will subsequently travel to the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in the artist’s native Washington, DC, and to the Art Institute of Chicago.

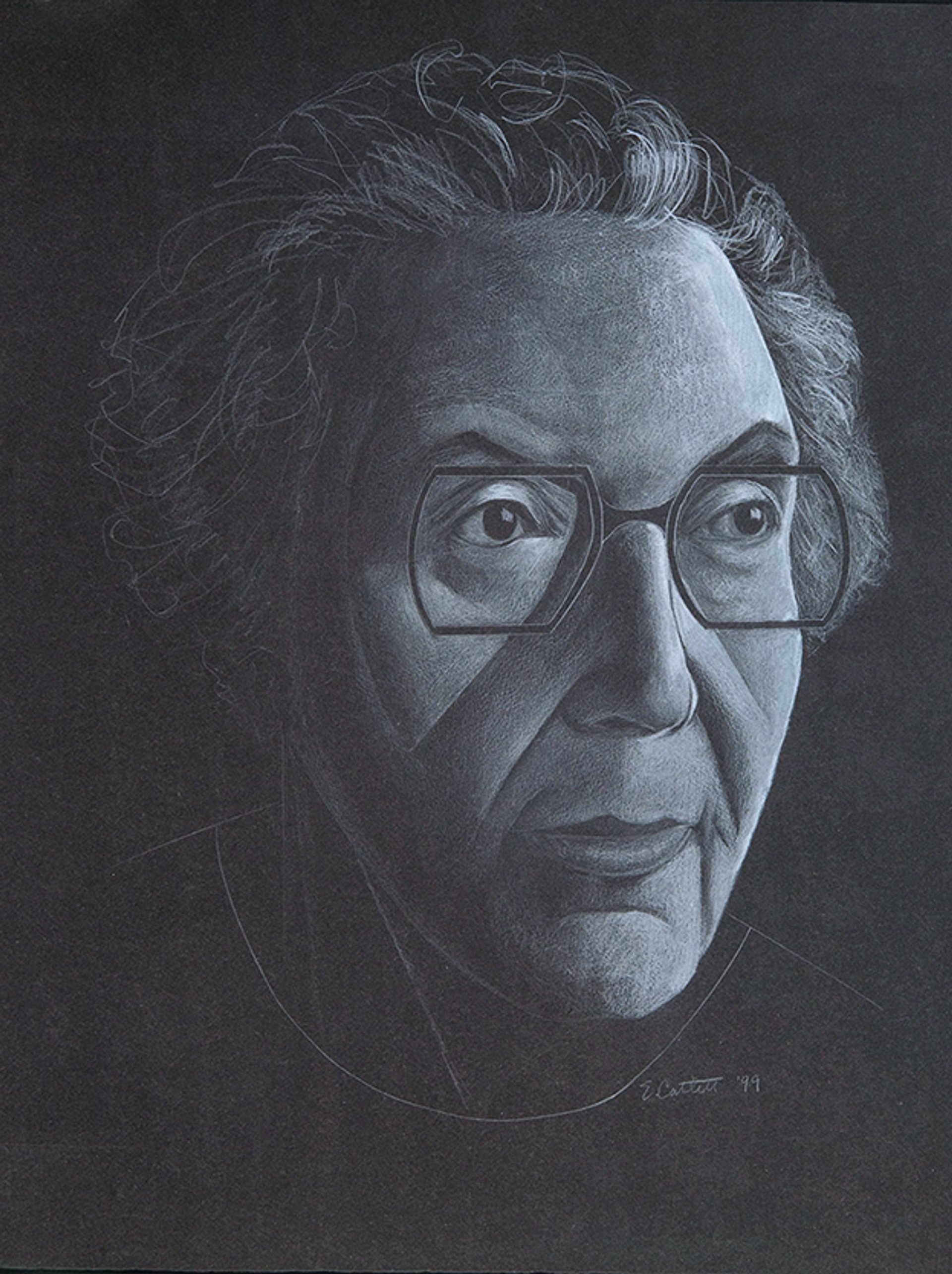

Elizabeth Catlett self-portrait from 1999

Image © Mora-Catlett Family/Licensed by VAGA at ARS, courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Working in the lingua franca

The exhibition brings together more than 150 objects spanning eight decades, from the sketches Catlett made as an undergraduate at Howard University in the 1930s to the public art commissions she completed in the 1990s and early 2000s. It will also chronicle the enormous material and formal range of her work, from the Social Realist prints she started making in the US in the 1940s and further developed in Mexico City after moving there, to her elegant and angular ceramic sculptures, Modernist wooden statues and more.

“Because her career spanned the 20th century, there are moments when her work is completely in lockstep with the artistic mainstream, particularly early on when she’s working in Social Realism, which was the lingua franca at the time, especially in the United States,” says Dalila Scruggs, the curator of African American art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, who has co-organised the show with the Brooklyn Museum’s Catherine Morris and Mary Lee Corlett, formerly of the NGA. “But also later in Mexico, with the emergence of Mexican Modernism, her work really resonates very deeply with the politics and aesthetics of both of those moments,” Scruggs says.

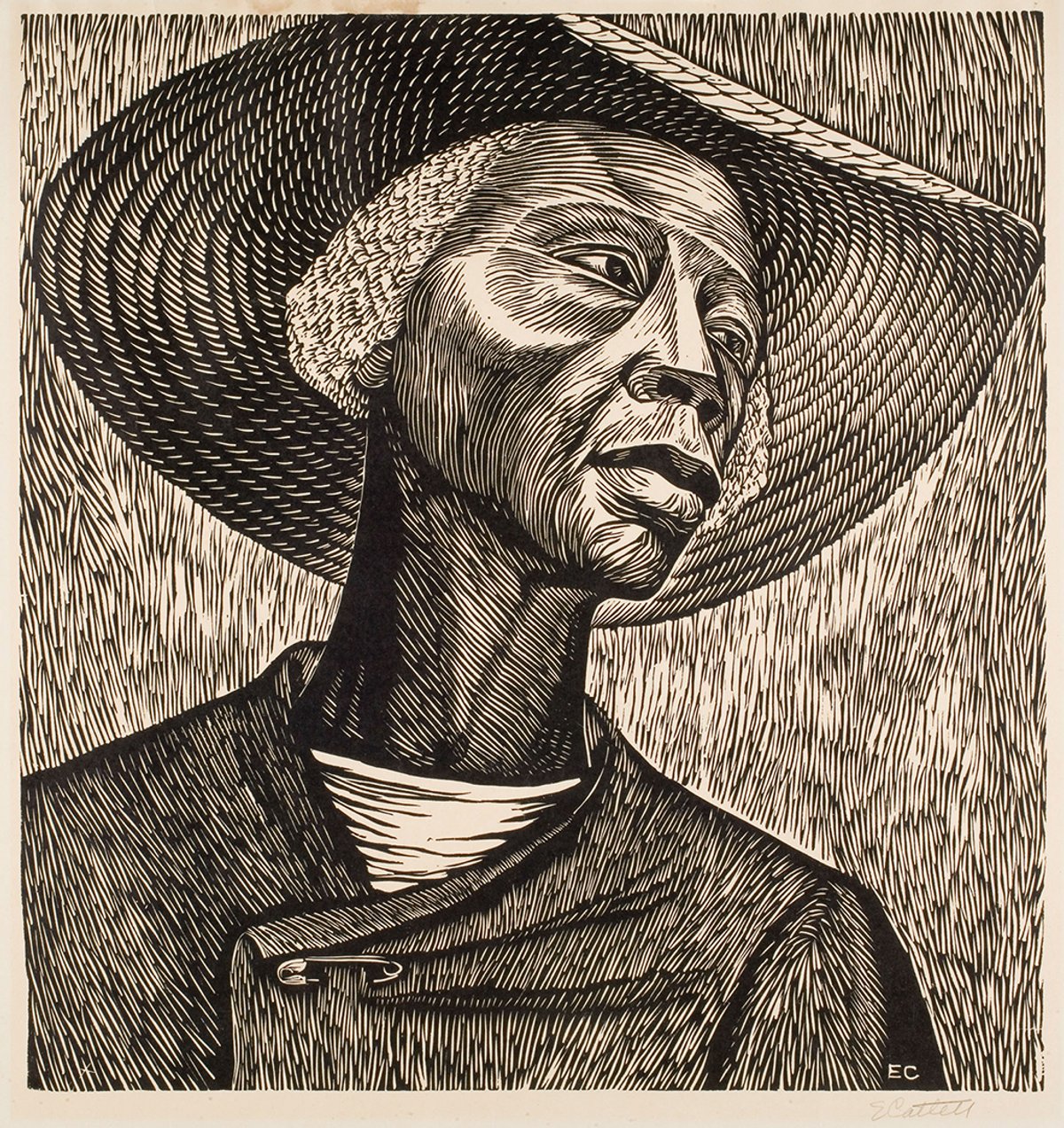

Catlett’s best-known works in the show emerged from very specific historical and political contexts but have a power that transcends them. She developed her 1952 linocut print Sharecropper, for instance, during her time at the Taller de Gráfica Popular arts workshop in Mexico City and drew inspiration from the labour struggles of farmworkers in the US and Mexico. With its heroising low angle, minimal palette and dazzling mix of contrasting patterns, the image has a sense simultaneously of quiet dignity and monumentality, evoking the Great Depression photographs by Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans.

Elizabeth Catlett’s wooden sculpture Black Unity (1968)

Image © Mora-Catlett Family/licensed by VAGA at ARS, photo by Edward C. Robison III

Black Power

The artist’s red cedar sculpture Homage to My Young Black Sisters (1968), with its streamlined female figure raising her fist, her face carved in bas relief and raised to the sky, synthesises elements of Modernist sculpture from Constantin Brâncuşi to Barbara Hepworth, and shows Catlett’s interest in traditional art from Africa and the Americas. It also attests to her support for the Black Power movement in the US and her commitment to international and intersectional feminist politics.

“Catlett’s feminism very much reflects an international feminist series of priorities that focused on the family, on aspects of community health, sustenance and safety in a way that paints a very different picture of 20th-century feminism than those that we’re largely exposed to in the United States,” Morris says.

In addition to giving a wider and more nuanced view of the overlapping political forces that informed Catlett’s life and career—from the civil rights movement in the US to the nascent sense of Black Mexican identity taking root in her adoptive country—the curators hope to recast a dichotomy that has been used to structure exhibitions and texts about her work: the contrast between her decades-long printmaking practice and her commissions for public monuments in the 1980s.

The sculptures

“What we’ve been able to do is to show a clearer link in the studio practice and the conceptualising of both making sculpture and making prints,” Morris says. “One of the goals of our exhibition is to present them as more relational and inclusive of each other.”

“For Catlett, printmaking had always been her public art, in line with the Taller de Gráfica Popular’s approach,” Scruggs explains, “but now you get to see what was a much more museum-centric or collector-centric approach around sculpture finally being brought to the people, in parks and in the street, open to everybody, through this public sculpture.”

• Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 13 September-19 January 2025; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 9 March-6 July 2025; Art Institute of Chicago, 30 August 2025-4 January 2026