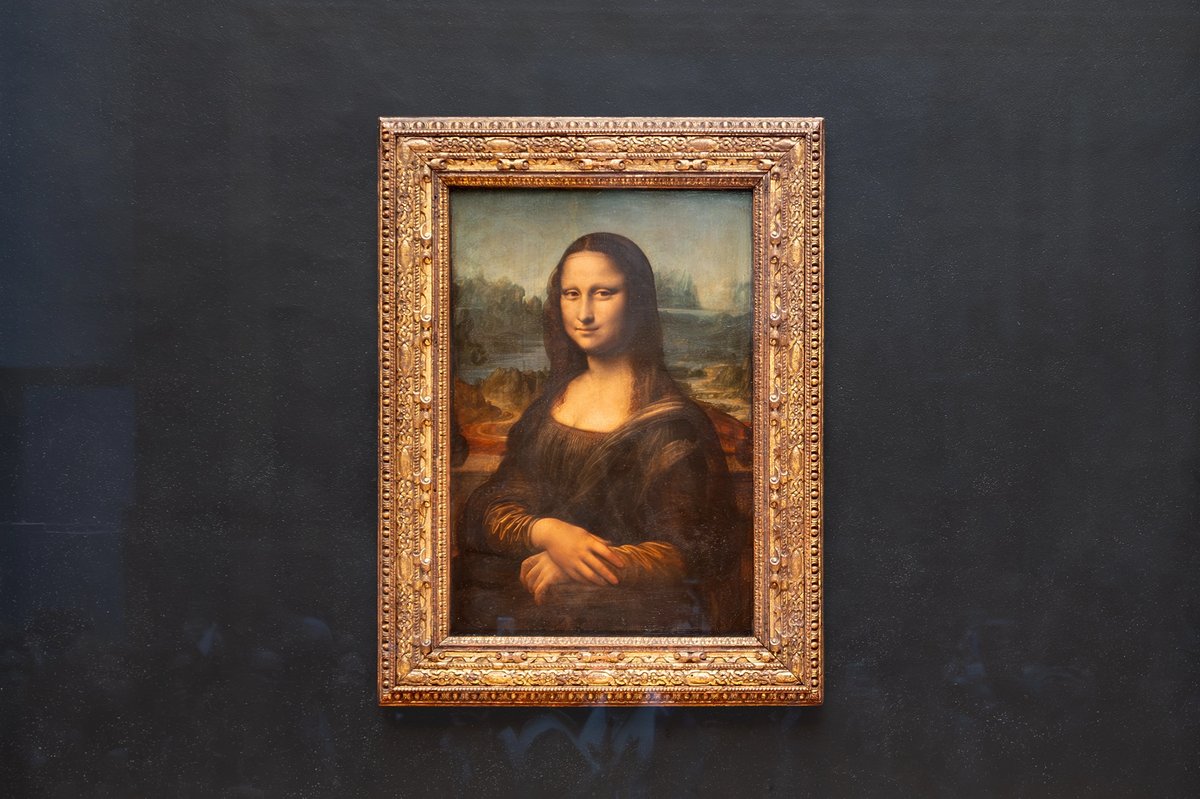

They are an odd couple to share a motivation. On one hand a nondescript odd-job man and occasional painter; on the other, a voluble archaeologist and former Egyptian minister of tourism and antiquities. Their wish? To achieve the repatriation of “stolen artefacts” that belong in Italy, most notably Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

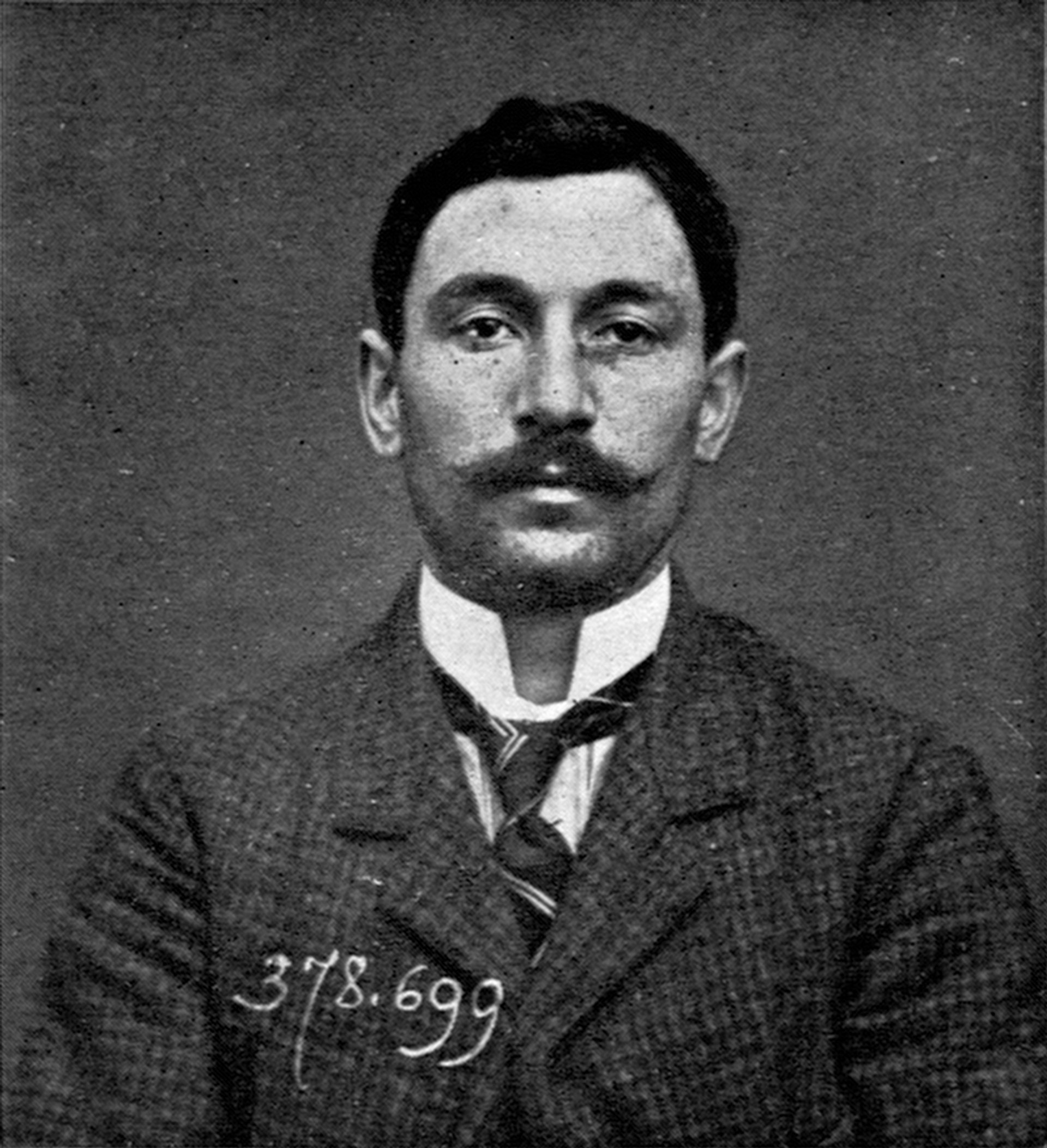

A major difference is that the former, Vincenzo Peruggia, actually did something about it.

He testified in the old prison in Florence in 1913, as “perpetrator of the theft of the Mona Lisa” two years prior. He tells how he “learned that a large quantity of paintings that were located in the Louvre had been stolen from Italy… During a break, I went into a small library… I read, and I also saw the photographs, that many paintings were stolen from Italy by Napoleon I. From that point, a desire was born in me, and I felt indignant, given my pride in Italy, and it came into my mind to give one of those paintings back to Italy.”

Early on 21 August 1911, he dressed in a worker’s smock that he had retained from working, the previous year, for a contractor who was commissioned “to clean the canvasses and put them under glass” at the museum. The glazing was intended in part to protect the masterpieces from protesting anarchists—though not climate protesters at this stage.

Vincenzo Peruggia in 1909. He claimed he had “learned that a large quantity of paintings that were located in the Louvre had been stolen from Italy…” and that ”from that point, a desire was born in me... and it came into my mind to give one of those paintings back to Italy”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Peruggia mingled inconspicuously with early morning workers at the Louvre that day. He lifted the Mona Lisa from its two iron hooks and removed its frame in a stairwell. Tucked under his smock, the panel was smuggled back to his humble bedroom. The scandal was such that the queues to see the vacant space on the grubby gallery wall exceeded those who had been to see the picture before its disappearance. It was more than two years before he surrendered his treasure to Giovanni Poggi, the director of the Gallerie degli Uffizi, in the forlorn hopes of its repatriation and a substantial reward.

The modern would-be repatriator, Zahi Hawass, has chosen to go down the political and media route. As The Art Newspaper reported, he said in an interview last weekend: “I will talk to the minister [Gennaro Sangiuliano] when I see him in Italy and I can join together to return Italy’s stolen artefacts. The Gioconda [as the Mona Lisa is also known] is the most important thing. It has to come back to Italy.”

Peruggia and Hawass’s shared premise is that there were illicit transactions before the painting joined the collection of Francis I in 1550, when it is recorded by the artist and chronicler Giorgio Vasari, or even that it was part of the Napoleonic war plunder.

What do we know about its actual acquisition? The painting, which depicts the Florentine bourgeois woman Lisa del Giocondo, was underway in 1503, but was almost certainly unfinished when Leonardo left Florence in 1507. The next we hear is in 1517, when the biographer Antonio de’ Beatis recorded the Cardinal of Aragon as visiting Leonardo in Amboise, central France. The painting is described by de’ Beatis as “a certain Florentine woman portrayed from life at the behest of the late Giuliano de’ Medici”. It seems that Giuliano, Leonardo’s patron in Rome, fancied Leonardo’s portrait as a wonderful picture, independently of the identity of the sitter. The Mona Lisa was the first portrait to transcend its function as a likeness to become a free-standing work of art.

Leonardo’s committed patron, Francis I, accorded him a huge salary and the grand manor house of Clos Lucé. The precise route by which the Mona Lisa entered Francis’s collection is still quite tangled, but he hardly had to indulge in some kind of illegitimate appropriation of a painting by his own artist. Leonardo was buried in France in 1519. There is no case for thinking that the Mona Lisa was literally “stolen” by the French king.

We may feel that the naïve Peruggia can scarcely be blamed for jumping to the wrong conclusion. Hawass has less excuse. If we are to have a measured discussion of restitution, we need to get the history right. Is Leonardo’s rightful heritage Florentine or Milanese (given that “Italy” was not an entity at this point)? It’s not quite Roman, but there is strong French dimension, and the French have more or less claimed him. Or is the great artist beyond such parochial localising?

- Martin Kemp is an art historian and emeritus professor of art history at the University of Oxford