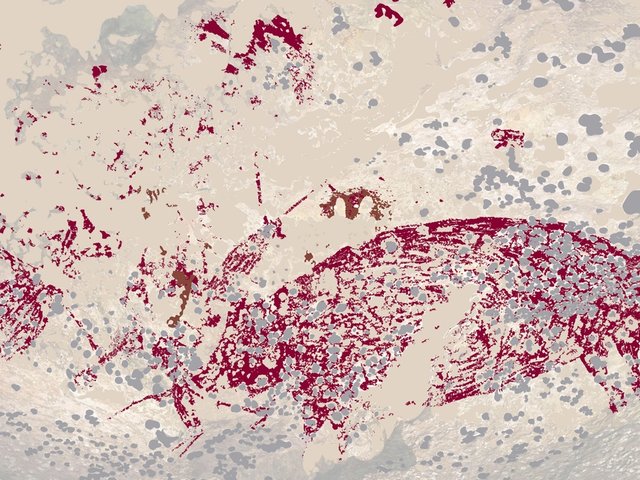

The discovery in 2019 of rock art drawings of animals—pig deer and dwarf buffalo—on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, dating to over 40,000 years ago, has revolutionised what we know of the origins of art. Before, it was thought that art, in the sense of images of things, appeared first in southern Europe, famously in the form of a standing figure of a lion (or perhaps a bear) carved from mammoth tusk—the so-called “Lion Man” found in the 1930s in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in southern Germany. Now we know that at the same time (40,000 years ago or more) humans were making representational images on the other side of the world. Mind-boggling stuff, and strong suggestive evidence that “art”, or at least image-making, began much earlier still, in Africa.

The first 30,000 or so years of human image-making—Ice Age art, in short—is one of the most exciting periods of cultural history, with discoveries and revelations coming thick and fast. Did the Neanderthals in fact make images? Is there a Lascaux to be discovered in Africa? How early did humans cross the Bering Strait to North America? Every decade the dates seem to fall back another few thousand years.

‘Separate from art history’

It’s perhaps not surprising that Ice Age images are often considered separate from art history—the domain of archaeologists. Most of the caves—Chauvet, Lascaux, Altamira—are out of bounds, and the smaller portable carvings in tusk and bone are often very fragile and rarely sent out for exhibitions. The deadening Eurocentric terminology devised to divide the Ice Age into periods—Aurignacian, Gravettian and so on—doesn’t help. And yet the very idea of “prehistory” (a word rightly shunned by some specialists) does little justice to the “speaking” quality of Ice Age images, and the truth that they stand not only at the start of the history of art, but occupy over three quarters of that history, so far.

Aside from the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, the British Museum (BM) is the only institution to include Ice Age art as part of a wider “world” collection of human cultural endeavour. The collections include many finds from French sites like the rock shelter of La Madeleine, excavated during the 19th century, and also objects found at Montastruc on the river Aveyron—notably the famous Swimming Reindeer, brilliantly carved from the tip of a mammoth tusk.

And yet Ice Age art has never been given its own permanent gallery at the BM. The standard for such a gallery might be taken from the 2013 BM exhibition Ice Age Art: Arrival of the Modern Mind, curated by Jill Cook, the keeper of the department of prehistory (as it is still known). The uncluttered display and focus on Ice Age art as illuminating the evolution of the modern human mind were a revelation, opening out a mysterious world in which the very idea of “art” seems to have been forged. Such a once-in-a-lifetime show was a good example, as T.J. Clark put it, “of the way the simple presence of things together in a room can outpace, not to say render faintly ridiculous, the best efforts of experts to make sense of them”.

There can be little doubt of public interest in human origins and Stone-and-Bone age art—the art equivalent of dinosaurs at the Natural History Museum. An Ice Age Gallery at the BM could go much further, however, shedding light on our contemporary predicament. For the first 30,000 years of our lives as image-makers, the only subject was animals. There are no known images of other crucial aspects of life—the sun and moon, plants, landscapes or indeed images of human animals, except for a small group of figurines of females. The evidence these animal objects provide of humans as one beast among many, and not necessarily the best suited for survival in an often hostile environment, has a direct bearing on our own time, when we have reduced animals to raw materials for subsistence. The Ice Age was nevertheless hardly Eden—most of the evidence points to humans wiping out species wherever they went.

An Ice Age Gallery would also show the shaping force of climate on human life. In his recent book The Earth Transformed: An Untold History, Peter Frankopan makes the crucial point that the fluctuations of global temperatures during the Ice Age, including a period of sudden warming, can help us understand the consequences of climate change in our own world, and the extreme changes in life that now seem sure to unfold over the rest of this century. Not that looking at the “bigger picture”, as Frankopan over-optimistically suggests, makes our plight any less urgent—the almost three degrees warming that seems now very likely, unless we make drastic changes, seems set to signal the end of the civilisation for which the BM has long prided itself as the custodian. And yet the evidence of the Ice Age shows how migration and adaptation—and in-built cunning—were the key to survival, even in the most challenging conditions. It is a matter of making connections, and it should not be forgotten that throughout the Ice Age, before rising sea levels flooded the area now known as Doggerland, the British Isles were still physically part of continental Europe.

• John-Paul Stonard is an art historian and author