“See in Venice, buy in Basel” is the phrase bandied about every two years, after collectors scour the Venice Biennale for hot new young artists and then move on to Art Basel to acquire them.

This year the curator of the Biennale’s 60th edition, Adriano Pedrosa, has chosen to focus on queer, Indigenous and self-taught artists, particularly those from the Global South. Many are being shown at the Biennale for the first time; some were known in their lifetime but, for various reasons, disappeared from public view. But does this recognition in Venice translate into inclusion at an art fair, and does it have an impact on prices?

Seba Calfuqueo is bringing her performance piece Ko ta mapungey ka to Basel Photo: Diego Argote, courtesy of the artist and Labor Gallery, Mexico City

Quite a few Indigenous artists’ work are on show, and for sale, at Art Basel this year. And even if it is their first outing in Venice, do not forget that some of these artists are already well established in their own countries—they just lacked the international exposure.

Nevertheless, “the Biennale effect is real, both for visibility and values,” says Thiago Gomide, a partner at the Brazilian gallery Gomide & Co. “People pay more attention when an artist is shown in Venice, and this creates more demand,” he says. Gomide’s São Paulo gallery is showing several Indigenous artists who were seen in the Arsenale in Venice at Art Basel. One is the Paraguayan Guaraní artist Julia Isídrez, who makes ceramic pieces based on the animals of her area. “She lives in a remote region of Paraguay. It took me four months even to get in touch with her, she has no phone,” Gomide says. “She was unrepresented until a year ago, but there is now a waiting list for her works.” Isidrez’s prices range from $15,000 to $20,000, and Gomide says they are now ten times higher than 18 months ago. “The exposure is making a significant change in her life, it is a huge deal for her,” Gomide adds.

Rising demand

In Art Basel’s Unlimited section, the Labor gallery from Mexico City is bringing a performative installation titled Ko ta mapungey ka (Water is Also Territory), (2020) by the Chilean Mapuche and non-binary artist Seba Calfuqueo. The Labor founder Pamela Echeverría, who began representing Calfuqueo 18 months ago, agrees that the Biennale—where Calfuqueo is showing in the Arsenale—has had a major boosting effect, notably for institutional interest. “Prices were ridiculously low, but now there is a lot more demand,” Echeverría says. Today this means paying $9,000 for small sculptures offered at the fair and $70,000 for the performance piece.

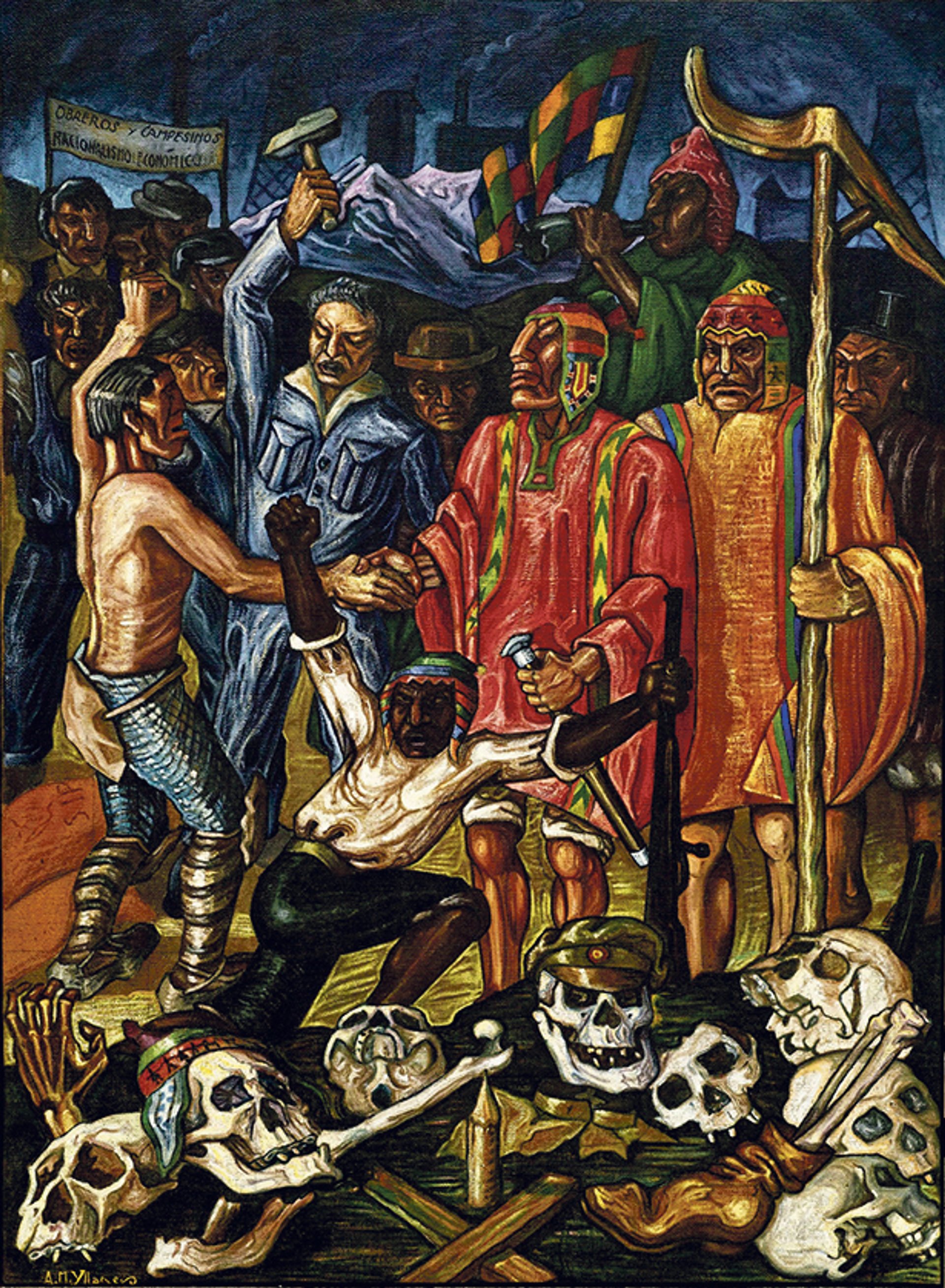

Viva la Guerra by the late Bolivian artist Alejandro Mario Yllanes is at Art Basel Courtesy of Ben Elwes Fine Art and Gomide & Co

Also in Unlimited is Marcados, a series of 37 images by the Swiss-born photographer Claudia Andujar (made in 1981-83, printed 2008-15). Andujar has devoted her life to defending Brazil’s Yanomami people, and the photographs, taken during a vaccination campaign, show individuals wearing numbered labels—something that reminded Andujar of genocide in Europe. This is one of just two complete sets (the other is in the Museum of Modern Art in New York) and is for sale at $2.5m. It is presented jointly by the São Paulo gallery Vermelho and Gomide & Co, and, if it sells, 5% of the price will be donated to the NGO Hutukara Associação Yanomami (Hay), which supports Yanomami people.

There are several other Indigenous artists at Art Basel who were selected by Pedrosa for the main exhibition in Venice, notably La Chola Poblete of Argentina, represented by Barro of New York, and the Angolan Sandra Poulson, represented by Jahmek Contemporary Art in Luanda.

The fair also features Indigenous artists who were not in Venice. For example, in the Features section, the Brazilian gallery Almeida & Dale is showing 25 paintings by Heitor dos Prazeres (1898-1966) mainly from the 1950s and 1960s. Dos Prazeres chose to explore the world of the post-slavery Black population and its fight for freedom and equality, at a time when most of the country was still focused on European culture. This did not go down well with the Brazilian authorities: his work was censored by the country’s military dictatorship in 1964.

Falling out of fashion

Prices for Dos Prazeres’s colourful, lively works range from $100,000 to $300,000. “Heitor had a measure of success in his lifetime, but then he fell out of fashion and visibility,” says the gallery director Paul Jenkins. “This was partly because of the concrete art movement, with its emphasis on abstraction, and also because he was a Black artist showing Black people.”

Another Indigenous artist, the Bolivian Alejandro Mario Yllanes, came to a mysterious end, probably assassinated by the political powers of the time. The largely self-taught painter and printmaker, born in 1913, had documented the culture and exploitation of the Aymara people, and in 1946 an exhibition in Mexico City’s Palacio de Bellas Artes featured 16 large-scale paintings and 20 woodblock prints by him.

The preface to that show was written by Diego Rivera, showing the international acclaim Yllanes enjoyed at the time. He was granted a fellowship by the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, but never collected the funds, and never exhibited again; he disappeared, and is thought to have died around 1960.

Yllanes’s work was rediscovered by the London gallery Ben Elwes Fine Art, which last year began exhibiting the 50 or so works Yllanes left behind. At Art Basel, in collaboration with Gomide & Co, the gallery is showing Viva la Guerra (1938), priced at $750,000, and the accompanying wood engraving Trincheras (1944), at $25,000.

This year the US pavilion at Venice featured Jeffrey Gibson, a Mississippi Choctaw/Cherokee painter and sculptor, and the first Indigenous artist to have a solo show there. It was an ostensibly feel-good exhibition with colourful, geometric patterns and beadwork on flags, sculpture, painting and a lively video of native American dancers. But some of the texts told a darker story, of exploitation and devaluation of native cultures.

Gibson has three galleries: Sikkema Jenkins & Co in New York, Stephen Friedman in London, and Roberts Projects in Los Angeles. At Art Basel, Sikkema is showing an acrylic painting on elk hide, Someone to watch over me (2023).

Gibson already has a secondary market and, for instance at Phillips last month, a beaded sign, Make me feel it (2015), doubled its estimate at $101,600. However, the “Venice effect” is not automatic, and a beaded figure by Gibson from 2014, Always After Now, just failed to sell at Sotheby’s in May, falling short of its $150,000-$200,000 estimate.

Nevertheless, “See in Venice, buy in Basel” remains true, and visitors will certainly be able to see a rich selection of work by Indigenous artists at the fair.