The Austrian-born Pop artist Kiki Kogelnik has been something of a “secret” outside her native country until very recently, says the director of her New York-based foundation, Stephen Hepworth. But with the first solo exhibition of her work in London now open at Pace Gallery and a major touring survey on view at the Kunsthaus Zürich, she is unlikely to remain under the radar for much longer.

Born in 1935, Kogelnik came of age in a devastated post-war Europe and was restless with the “desire to escape, to find a space where one can be free”, Hepworth says. From the arts academies of Vienna she travelled to Paris, where a fateful encounter with the Abstract Expressionist painter Sam Francis propelled her move to New York. Making the city her home in 1962, she plunged headlong into “the new direction” in painting, now known as Pop.

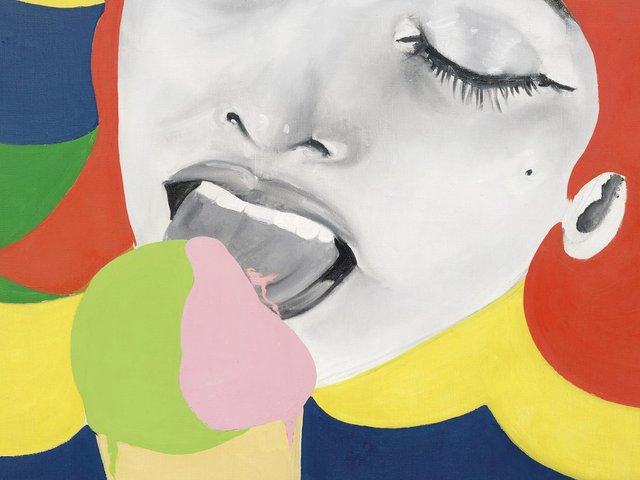

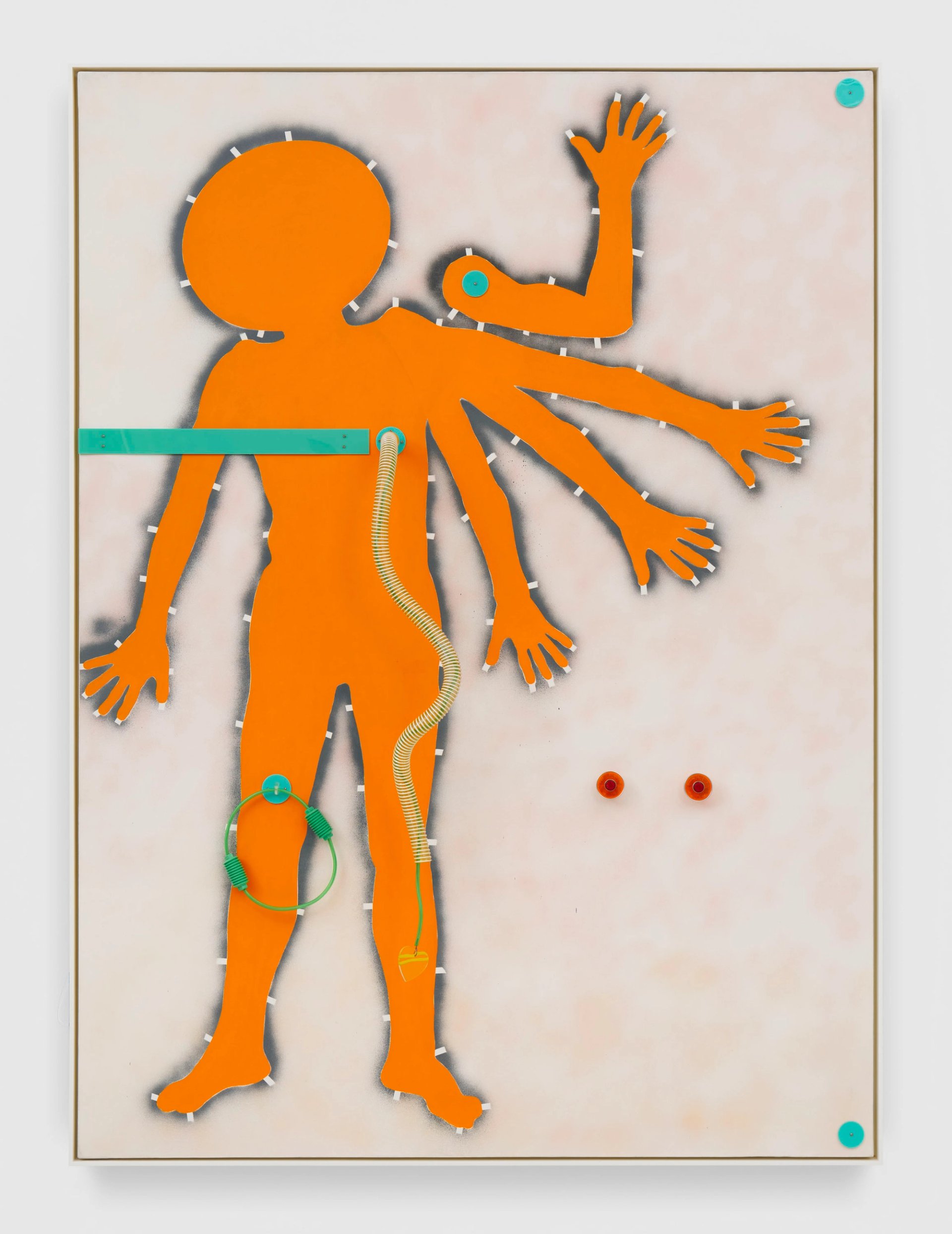

Kogelnik’s enthusiastic embrace of new directions would become a defining characteristic of her work. Even as she settled into her signature painting style of sleek and psychedelically coloured silhouettes, she continually experimented with new materials. She applied swaths of silver paint, acrylic pigments and gaseous spray-can effects to her 1960s canvases of floating cosmonauts and fragmented bodies, developed against the Cold War backdrop of nuclear anxiety and the space race.

Kiki Kogelnik, Astronaut (1964) Image: © Kiki Kogelnik Foundation

Ranging across paintings, sculptures, works on paper and ceramics from the early 1960s to the late 1980s, the Pace show shines a light on the central duality in Kogelnik’s art between “life and death—or possible death”, as Hepworth puts it. Her exuberant colour palette masks sinister symbols, like falling bombs, a gun and a lurid pink skeleton. “There’s always the sense of the fragility of this world that she’s imagining,” Hepworth says.

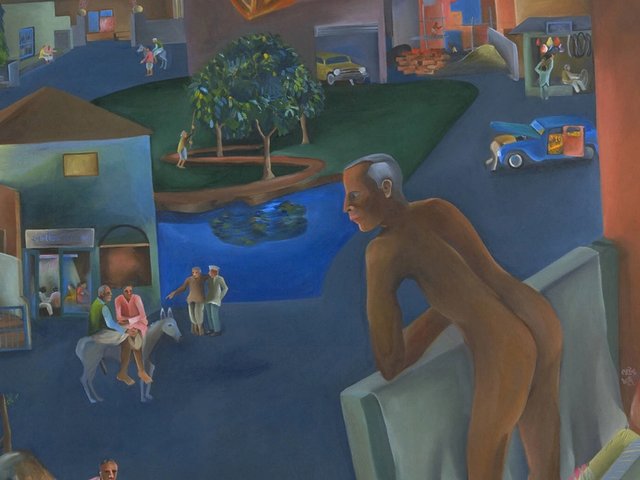

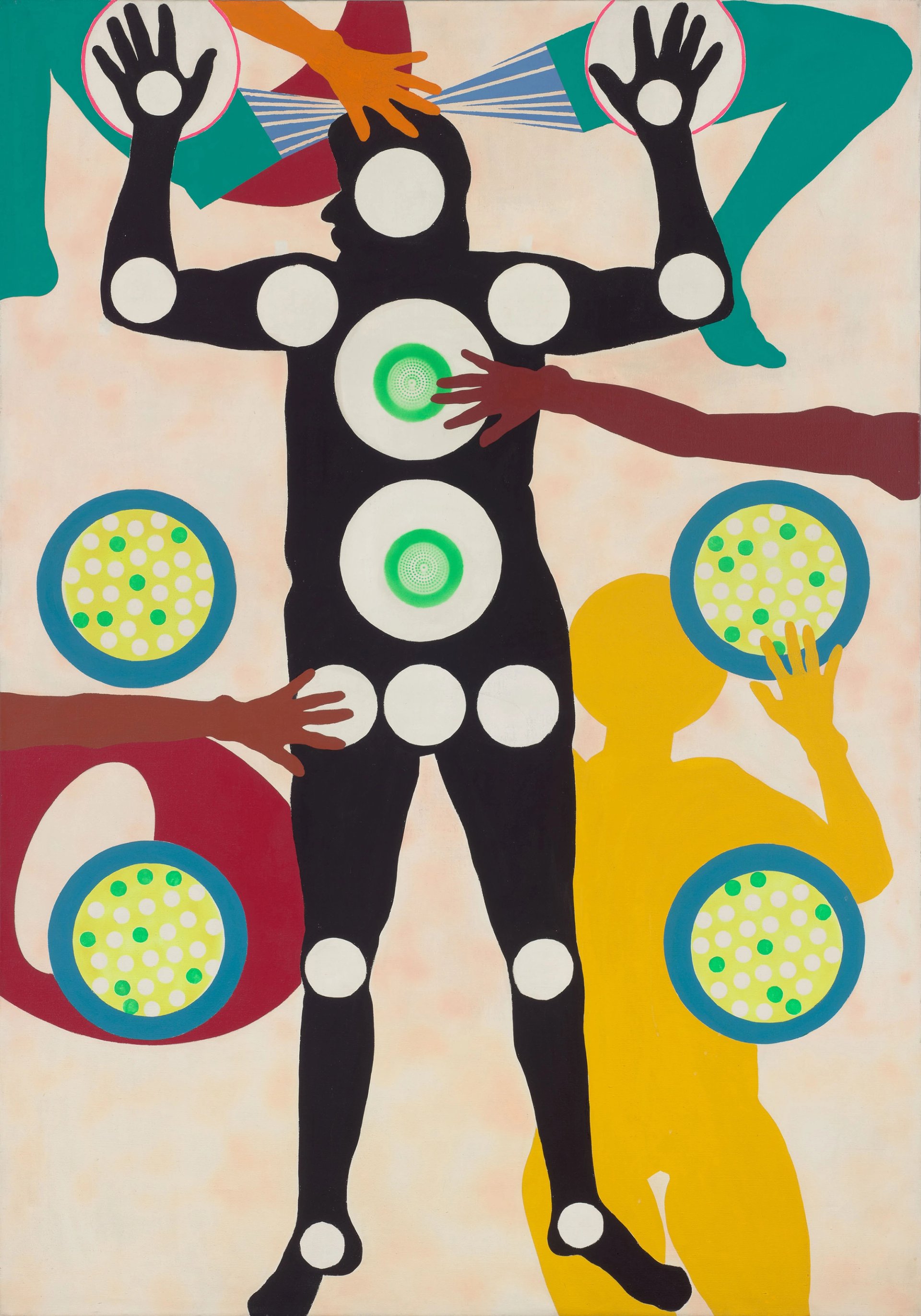

Kogelnik favoured sci-fi speculations over any straightforwardly political commentary on Cold War reality. Body parts often appear with futuristic augmentations, as in the neon-yellow plexiglass work Plug-In Hand (1968) and the painting Artificial Man (1965), whose multi-armed, helmet-wearing protagonist has a plastic heart dangling off a length of tubing.

Kiki Kogelnik, Artificial Man (1965) Image: © Kiki Kogelnik Foundation

A highlight of the show is a group of 12 drawings from Kogelnik’s Robots series, produced in 1966 and 1967 during a stay in London with her doctor husband. Rediscovered in the archives of the Kiki Kogelnik Foundation, the 90-strong series charts the journey of very human-looking robots into space. Their anatomically precise bodies and heads are the imprints of “rubber stamps, which were used by doctors at that time to write their diagnosis”, Hepworth says. After their moment of ecstatic union with the cosmos comes, at least for the female cyborgs, their fall and violent destruction.

Following the moon landing in ‘69, when she staged a happening in Vienna, space exploration lost its utopian allure for Kogelnik and her work transformed anew. Without a studio for a few years while she juggled art with motherhood, she was unable to paint. Her practice of depicting bodies in silhouette, based on tracings of the real-life bodies of her friends and lovers on brown paper, progressed into multicoloured vinyl cut-outs she called the Hangings.

Scissors became “as important to her as a paintbrush”, Hepworth says, and she wields a giant pair in an empowered self-portrait from 1971, standing astride the collapsed shells of bodies. The Pace show includes this silkscreen print as well as Seventh Ave. People (1986), a cheerfully macabre installation of vinyl figures hanging from a clothes rack—a nod to Manhattan’s Garment District.

Kiki Kogelnik, Seventh Ave. People (1986) © Kiki Kogelnik Foundation

Though the self-portrait is titled Womans Lib, Kogelnik did not identify with the feminist movement gathering pace in the US at that time. “It’s like Pop, she defines herself in opposition. But actually, she absolutely is [a feminist] through circumstance,” Hepworth says.

Grappling with gender inequality in her private and professional life, Kogelnik produced a series of large-scale 1970s paintings of lithe, dead-eyed women that seem to parody the fashion models from magazines. Although she was exhibiting and selling works through galleries in Vienna and New York during her lifetime, she did not have financial independence or recognition on par with her male counterparts.

“How many female Pop artists do you know?” Hepworth says. “It was very male-dominated. The women were always the secretary, the assistant, the wife, the girlfriend.”

He contends that Kogelnik’s work was “far more complex” than the Pop label would suggest, anyway. “I am not involved with Coca-Cola,” she wrote in 1966. “I am involved with the technical beauty of rockets, people flying in space and becoming robots.” Her fluid, multimedia practice was always less concerned with the objects of consumer society than the human bodies soaring through the modern age, and sometimes fragmenting apart.

While there are streets named after Kogelnik in Austria, the foundation hopes that greater international exposure of her work can raise her profile elsewhere. “Our desire is just to bring this work to attention, and quite honestly, it does the work itself,” Hepworth says. “I think people are going to be amazed by it.”

• Kiki Kogelnik: The Dance, Pace Gallery, 5 Hanover Square, London, 24 May-3 August 2024

• Artist Paulina Olowska will lead a tour of the exhibition at 5pm on 31 May for London Gallery Weekend

• Kiki Kogelnik: Retrospective, Kunsthaus Zürich, until 14 July 2024

• The Art Newspaper is a media partner of London Gallery Weekend