High in the Entoto Mountains, overlooking the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa, an ambitious new cultural centre that brings together art, ecology and local building traditions is taking shape.

Undulating structures designed to house exhibition spaces, a library, a culinary school, a children’s activity centre and more float above the ground, supported by wide, circular columns. A waterfall splashes next to an exercise area. The hillside is freshly planted with young native trees—juniper, acacia and hagenia.

Called Zoma Village Entoto, the complex is expected to open in September. It was conceived by Elias Sime, one of Ethiopia’s most successful artists, and Meskerem Assegued, an anthropologist and curator. Sime’s art is everywhere in the centre—in pavements inlaid with butterflies and on walls carved with hieroglyphic birds. Large, sculpted ducks sitting on tall concrete pillars peer out over the landscape.

Elias Sime’s art is present all around Zoma Village Entoto

Photo: Alice Hendy

The buildings have been designed to avoid harming the habitat of creatures from hyena to bees

Assegued and Sime—who sketch copiously in preparation for their projects—drafted the initial designs, working with structural engineers to ensure their plans could be built. “You just follow your natural instincts,” Assegued says. “For instance, how do you do something without killing the trees or destroying the landscape?” The buildings, she says, have been designed to avoid harming the habitat of creatures from hyena and dik-dik (a small antelope) to wild rabbits and bees.

Abiy Ahmed, the Ethiopian prime minister, granted Sime and Assegued the land on which Zoma Village Entoto is built, but the financing comes entirely from its creators. It is their most ambitious endeavour to date. More projects are on the way, including a reinvigoration of the Sof Omar caves in the south-east of the country.

Sime and Assegued build slowly, sustainably and traditionally—in stark contrast to the high-rise structures that have sprung up in Addis Ababa in recent years. They have studied the vernacular architecture of Ethiopia, India and Mexico.

The mud walls of Zoma Village Entoto’s predecessor, Zoma Museum, depict everything from caterpillars to the Ethiopian Ge’ez numerical system

Michel Temteme

“Although modernity is unstoppable, we believe it is good to think about alternative construction techniques for our survival,” Assegued says. “We think techniques such as the use of lime for mortaring, various types of mud and straw buildings including adobe, cob and rammed earth are environmentally sound and healthy.”

Their collaboration began in the 1990s. Sime, who has a collateral event exhibition at this year’s Venice Biennale, is known for his intricate wall works formed out of a range of found objects. He is represented by the prominent James Cohan gallery in New York. Assegued, meanwhile, has curated shows in Ethiopia and abroad, served on selection committees for the Dak’Art Biennale in Senegal and the Venice Biennale, and written and contributed to books on folklore, music and art.

Stupendous diversity

Not long after they first met each other, Sime invited Assegued to his studio in Addis Ababa. “I was stunned,” Assegued says. “The diversity of the work—it was almost anthropological.”

Assegued told him about her vision for an arts centre. She had been making sketches of old buildings for years, using them to plan a site that could incorporate similarly enduring structures. “Elias made it happen,” she says.

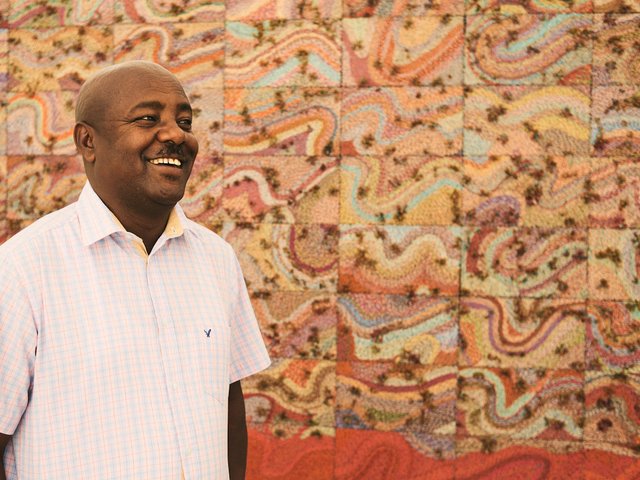

Meskerem Assegued and Elias Sime at Zoma Museum

Photo: Alice Hendy

They started with Zoma Contemporary Art Centre, a small exhibition space, more than two decades ago. It moved and reopened as Zoma Museum, a school and art institution in 2019. Located down a quiet alley in the south of Addis Ababa, it is a sprawling haven, built piece by piece over several years on what was once polluted land.

Twisting paths lead visitors through a forest of papaya, lemon, guava and other indigenous trees and past buildings of a style known as “chika bet”, made of natural materials such as mud and straw. Almost all these structures have a unique sculpted exterior, created by Sime. One depicts interlinked chains, others a swirling abstract pattern, while some feature caterpillars, the symbol of the school. Birds such as the Abyssian thrush, the red-billed firefinch and the Ethiopian bee-eater have been sighted in this oasis of nature in the capital.

We teach people to be human here

Zoma Museum’s school has a science lab and offices, but also kitchen facilities where the children simultaneously learn cookery and maths, an allotment where they grow vegetables, and a shed where they learn to milk cows. “We teach people to be human here,” Assegued says. A student hugs her as she enters a room.

A view of the grounds at Zoma Museum

Photo: Alice Hendy

Ethiopia made huge progress in eradicating poverty between 1995 and 2015—the percentage of people living in poverty fell from over 45% in 1995 to around 23% in 2015, according to the International Monetary Fund. Since then, the country has been hit hard by Covid-19, a prolonged drought in the Horn of Africa, and civil war—including a new conflict in the northern region of Amhara and another ongoing in the central region of Oromia.

Such factors have limited international investment, though the Chinese government has been a notable exception, pouring billions into infrastructure projects such as railways and roads. The most prominent of the new, Chinese-backed buildings in Addis Ababa is the headquarters of the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, which became the tallest building in East Africa when it opened in 2022.

Local authorities, however, have been investing in new public spaces such as parks, playgrounds and museums—as well as green policies such as promoting the use of electric cars. Media outlets such as Kenya-based news website The Elephant have questioned these priorities in light of the country’s economic and humanitarian struggles.

One building is shaped like two joined camels, with a painting of lush green branches across one ceiling and a camel-filled landscape across another

Zoma Museum caught the attention of the Ethiopian prime minister, who commissioned Sime and Assegued to create a mini-Zoma a few miles away at Unity Park, which opened in October 2019. Floor tiles and seats are carved with Sime’s nature motifs. One building is shaped like two joined camels, with a painting of lush green branches across one ceiling and a camel-filled landscape across another; another building is shaped like a turtle, with head and fins crafted out of spoons.

Assegued says: “Zoma is that attempt to answer the question, how do we understand being human? How can we be human without the plants? How can we be human without the arts?”

Sime and Assegued say they made a conscious decision not to worry about the cost of Zoma Village Entoto, though they estimate it to be “in the millions”. While they expect to one day make a return on the investment and plan to outsource the day-to-day management of the site, they say their primary goal is to provide an enduring, much needed space for artists and the wider population. As Sime often says when discussing his work: “It’s love.”