When Gavin Stamp died in 2017, it was generally assumed that the British “interwar” architecture book, on which he had been working for a good number of years, would never appear. It turns out that he left a well-advanced manuscript, which his widow Rosemary Hill, the architectural historian and A. W. N. Pugin biographer, has prepared for publication as Interwar: British Architecture 1919-39. This must be a cause for gratitude and rejoicing, as Stamp was a superb writer with an unmatchable knowledge of the period concerned.

Stamp was born in 1948, in Bromley, Kent, where his father had a small chain of grocery shops. He won a free place to the public school Dulwich College, where proposed alterations to its striking Victorian buildings led him to make the first of a lifetime of protests against what he considered “vandalism”. He went on to read history at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, with its additions by the eminent Victorian architect Alfred Waterhouse. Stamp’s PhD thesis was on George Gilbert Scott Junior (1839-97), the eldest son of the great Sir Gilbert (who designed the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras Station and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, both in London), himself an architect of great skill and sensitivity. The thesis led to the publication of An Architect of Promise (Shaun Tyas, 2002).

Stamp was for most of his life a freelance journalist. However, in 1990 he became a lecturer in architectural history at the Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art, rising to a professorship by the time he left (to return to London) in 2003. While in Glasgow, he founded the Alexander Thomson Society, to study and defend the work of that eminent Scottish architect (1817-75), known as “Greek” Thomson, and lived in Thomson’s own house, 1 Moray Place, Strathbungo, Glasgow.

Stamp invented various awards, including the Emperor Nero Award for fiddling while Rome burns

His most notable journalism was from 1978 until his death, under the pseudonym “Piloti”, as author of the column “Nooks and Corners of the New Barbarism”, which had been founded in the fortnightly satirical magazine Private Eye by the poet and writer John Betjeman. His fearless criticism had a remarkable effect, and he scorned threats of prosecution for libel. He invented various awards, including, just before his death, the Emperor Nero Award for fiddling while Rome burns. The first winners were the UK members of parliament—whom he described as “a collection of mediocrities”—for refusing to leave, in order to restore, the crumbling Palace of Westminster. However, it would be a mistake to think that negative attack was his only achievement, as he wrote plentifully and perceptively on many topics in books, articles and reviews. He was a powerful supporter of the Victorian and Twentieth Century Societies.

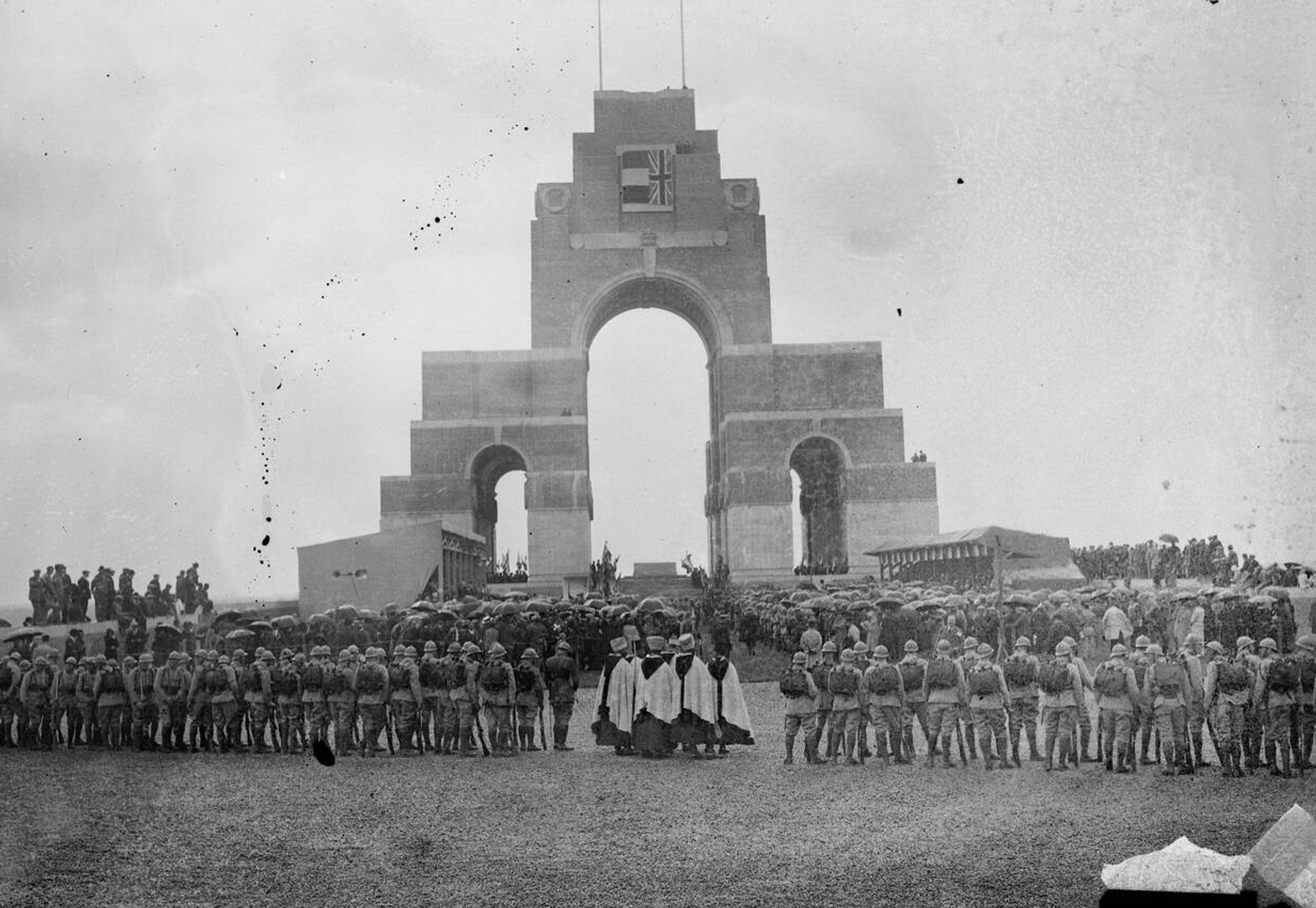

Edwin Lutyens’s Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme (pictured at its 1932 inauguration) was the subject of Gavin Stamp’s 2006 book © Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Hill provides a fascinating preface to Interwar: British Architecture 1919-39, paying tribute to the Twentieth Century Society for its support, especially with the numerous illustrations, which are largely the work of its unofficial photographer John East. As Hill points out, the 1920s and 1930s were complicated by the fact that some architects were carrying on from the earlier Edwardian period, while others were signed up to Modernism. The shadow of the Great War lay heavy, and Stamp made a particular study of its memorials. The first chapter of the book, “Armistice”, which focuses on Edwin Lutyens’s Thiepval Memorial, a 45m-tall arch in Picardy in France unveiled in 1932, carries on the concern that had inspired Stamp’s The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme (Profile Books, 2006).

Bathtubs and dolls’ houses

The second chapter, “The Grand Manner”, unsurprisingly also features Lutyens, drawing on Stamp’s familiarity with colonial India. He quotes Christopher Hussey’s account of Middleton Park, Oxfordshire, where he called the “sumptuous vaulted bathroom lined with white marble and pink onyx”, made for the Countess of Jersey, a former American actress, “a notable instance of the between-wars cult of the tub”. Sadly, it was removed when the house was converted into flats by an architect who claimed to be at least as good as Lutyens. Stamp would have known how to deal with that. The chapter ends with Lutyens’s Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House of 1924, displayed at Windsor Castle. Stamp writes: “An astonishing amount was written about the Doll’s House, in an embarrassing orgy of whimsy, sycophancy, deference and infantilism, that can be interpreted as the profoundly conservative response of a disoriented nation to the frightening challenges of the post-war years.”

The third chapter, “Swedish Grace”, reveals Stamp’s remarkable knowledge of European architecture. He points out that “British architecture has never, perhaps, before or since been so open to ideas from abroad as it was between the two world wars”. The chapter “Tutankhamun” discusses not just the Egyptian Revival, but Art Deco, covering London’s Hoover Building and lamented Firestone factory, and the Battersea and Bankside power stations: to a great extent, the last was preserved because of Stamp’s tenacious support, leading to its transformation as Tate Modern. It was hoped that he would write a book about their architect, Giles Gilbert Scott (son of “an architect of promise” George Gilbert junior) in 1979, but it was not to be.

Stockbroker’s Tudor

The next chapter, “Merrie England”, deals sympathetically with what Osbert Lancaster called “stockbroker’s Tudor and by-pass variegated”. This was the style of Stamp’s own birthplace, a bungalow on the Orpington bypass. The chapter covers the many manifestations of Neo-Tudor, including Lutyens’s Campion Hall at Oxford University. In describing the chapel there, Stamp writes that “the pews rest on an undulating base painted bright red in contrast to the black and white marble floor”. He might have mentioned that Lutyens got the idea from the 17th-century chapel at Y Rug, Merioneth, Denbighshire, which Lutyens and Herbert Baker (1862-1946) had visited on a walking tour of Wales and Shropshire in 1888. Stamp quotes the brilliant critic Robert Byron (1905-41), whom he greatly admired, on Baker, his “bête noire”, but the recent biography of Baker (John Stewart, Sir Herbert Baker: Architect to the British Empire, McFarland, 2021) certainly makes one feel more sympathetic towards him in his disagreement with Lutyens over New Delhi. However, Baker’s rebuilding of most of John Soane’s late-Georgian Bank of England gets no quarter from Stamp.

It is not surprising that Stamp is so sympathetic to Neo-Georgian. He praises the post offices built all over the UK, many now sadly closed and converted to other uses. Of course, he particularly celebrates the telephone boxes designed by Giles Gilbert Scott: it is largely due to his advocacy that so many survive. Stamp is equally sympathetic to “Modern Gothic”, writing of Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral Church of Christ: “The huge and continuing popular success of [Giles Gilbert] Scott’s masterpiece affirmed the continuing importance of church architecture and of building to last”.

The last chapter, “The Shape of Things to Come”, accounts for the patchy and not entirely successful introduction of the “Modern” style to Britain. He quotes John Summerson: “the Modern Movement had made very little headway in Britain by 1939”. However, what had actually been achieved—including Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff’s De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea (1935) and Joseph Emberton’s Blackpool Casino (1937-40)—is treated with the same critical sympathy as the other styles.

In his fine obituary in The Guardian, Ian Jack wrote of Stamp that “in later life, he sometimes fretted that he had ‘wasted his time’ writing journalism rather than ‘proper books’”. Interwar is most definitely a proper book, and a wonderful memorial to a great writer.

• Interwar: British Architecture 1919-39, by Gavin Stamp, published by Profile Books, 568pp, 38 colour illustrations with b/w,

£40 (hb), 7 March