“Fifth Avenue” today suggests expensive shops and hotels, but Mosette Broderick’s fascinating book tells how it became the most fashionable address in town, then lost its cachet. Although the street already existed, it was the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 that gave it its name. The Washington Parade Ground, on the site of a cemetery, became Washington Square in 1826. The houses here, in a severe Greek Revival style, became sought after by wealthy merchants, and development soon continued up Fifth Avenue. Broderick tells the fascinating story of how this gradually went further and further north, but eventually came to a halt as the rich upper classes no longer wanted grand houses in the city.

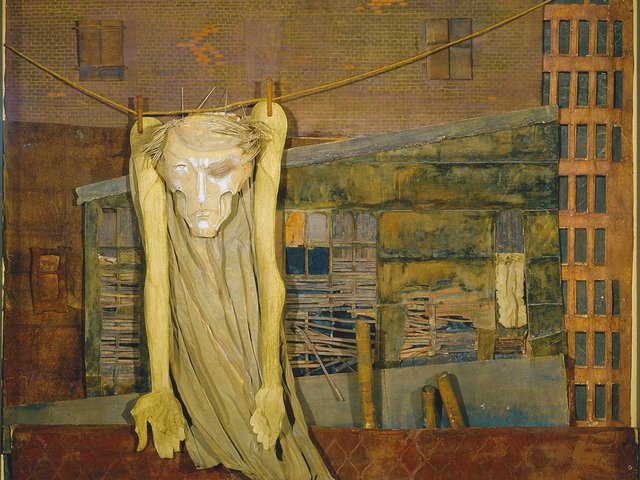

But while they still did, the architectural ambition of the houses became increasingly remarkable. Some remain, though not as private houses, but many have been demolished. The cover shows the wrecking of one of the grandest, built by William A. Clark (nicknamed “Clark’s Folly” and denounced by Mark Twain as “disgusting”), who lived there in a family of three for just 12 years. The huge French-style pile was designed by the obscure architectural practice of Lord, Hewlett and Hull. Clark left his collection of paintings (a popular status symbol on the street) to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which refused it. Other houses, however, were designed by distinguished architects, such as Richard Morris Hunt, Warren and Wetmore, Horace Trumbauer, Carrère and Hastings, and McKim, Mead and White. The patrons included such names as Vanderbilt, Whitney, Frick, Rockefeller and Stuyvesant.

One of the reasons why the fashionable moved north was the conversion of houses into flats and lodging houses, and the arrival of retailers. Later, hotels replaced private houses. Even more unwelcome was Madame Restell, who was a notorious abortionist. William Henry Vanderbilt was put off building on his chosen site by her proximity, but after she slit her throat in the bath the coast was clear.

Colourful characters

The cast of characters is amazing, and Broderick knows all about them. August Belmont was called “the King of Fifth Avenue”. His wife, a daughter of Commodore Matthew Perry, was an admired setter of fashion, and helped to make her Jewish-born merchant husband acceptable to society. Their house, a plain but handsome building by an obscure English architect, Frederick Diaper, was demolished after their deaths to make way for a store. Further north, the huge Fifth Avenue Hotel (completed in 1859) was where Edward, Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII) stayed in 1860. “The flashiest house in Manhattan”, actually on Madison Avenue, was also designed by an English architect, Thomas R. Jackson, for the stockbroker Leonard Jerome, whose daughter Jennie married Lord Randolph Churchill.

Inevitably men came forward to manage society. Isaac Hull Brown was a former carpenter who became sexton of Grace Church, and organised many of the Prince of Wales’s engagements, but he was overtaken by Ward McAllister, son of a banker, who specialised in balls and dances, held particularly at the restaurant Delmonico’s, which arrived on Fifth Avenue in 1862 (and later became the fashionable restaurant of the “Gilded Age”). McAllister was supported by Caroline Astor, but was later disdained. Marietta Reed, daughter of a greengrocer, married Paran Stevens, manager of the Fifth Avenue Hotel. He had a house built by Richard Morris Hunt, and later a huge building intended to provide “high-end” apartments. This later became the Victoria Hotel. Marietta’s son Harry became engaged to Edith Jones, but her mother disapproved, and she went on to marry Teddy Wharton, acquiring the married name by which she made her name as a novelist.

The architectural ambition of the houses became increasingly remarkable ... but many have been demolished

As the Gilded Age began, the new arbiter of taste was the merchant Peter Marié, who had more than 300 society women painted for his collection of miniatures. The most sought-after event was the Patriarchs’ Ball. By now the lower part of Fifth Avenue was largely occupied by lodging houses and the garment trade. The owner of New York’s first department store, A.T. Stewart, built a very grand house at 34th Street. His collection of 19th-century art was of outstanding quality. However, he was not acceptable socially. Caroline Astor said that she bought carpets from his store but would not invite him to walk on them.

Above 37th Street, the progress of Fifth Avenue was held up for a time by the huge Croton Reservoir, and the steep hill up to it, but the problem did not last long. Real estate values grew at an astonishing rate, and grand houses gradually drove out the abattoir and various shacks. One of the grandest was built by William Henry Vanderbilt: it had lavish interiors by the Herter Brothers. His son William Kissam Vanderbilt had a remarkable French Gothic house built by Richard Morris Hunt, while another son, Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr, had a large French Renaissance house designed by George B. Post. By the early 20th century the great days of Fifth Avenue were over.

The book is illustrated with a wealth of old photographs, and has appendices giving details of patrons, architects and builders.

• Mosette Broderick, Fifth Avenue: Architecture and Society: A History of America’s Street of Dreams, Unicorn Publishing, 320pp, 200+ illustrations, £30 (hb), published 26 October 2023

• Peter Howell’s latest book is The Triumphal Arch (Unicorn Publishing 2021)