The Renaissance master Michelangelo (1475-1564) was not yet 30 when he finished his monumental sculpture David (1504), miraculously fashioned out of a single block of Carrara marble regarded as unworkable. He was only in his late 30s when he all but single-handedly finished the immense frescoed ceiling of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel. But Michelangelo lived to be 88, and he went on working—by some measure, on an even grander scale—until the end.

An exhibition at the British Museum in London will look at Michelangelo’s final phase, starting with his return to Rome from Florence in 1534, at age 59. It was during this period that he finished work on The Last Judgment, the Sistine Chapel altar wall’s towering fresco, and also managed to remake Papal Rome with a series of architectural projects that still mark the city. Michelangelo: the Last Decades conjures up the artist’s state of mind and key relationships during this final third of his life, with the help of around 50 Michelangelo drawings and more than 50 additional works of art and objects.

The fresco treats the human body as the work of God, not as something explicitly made to excite desire

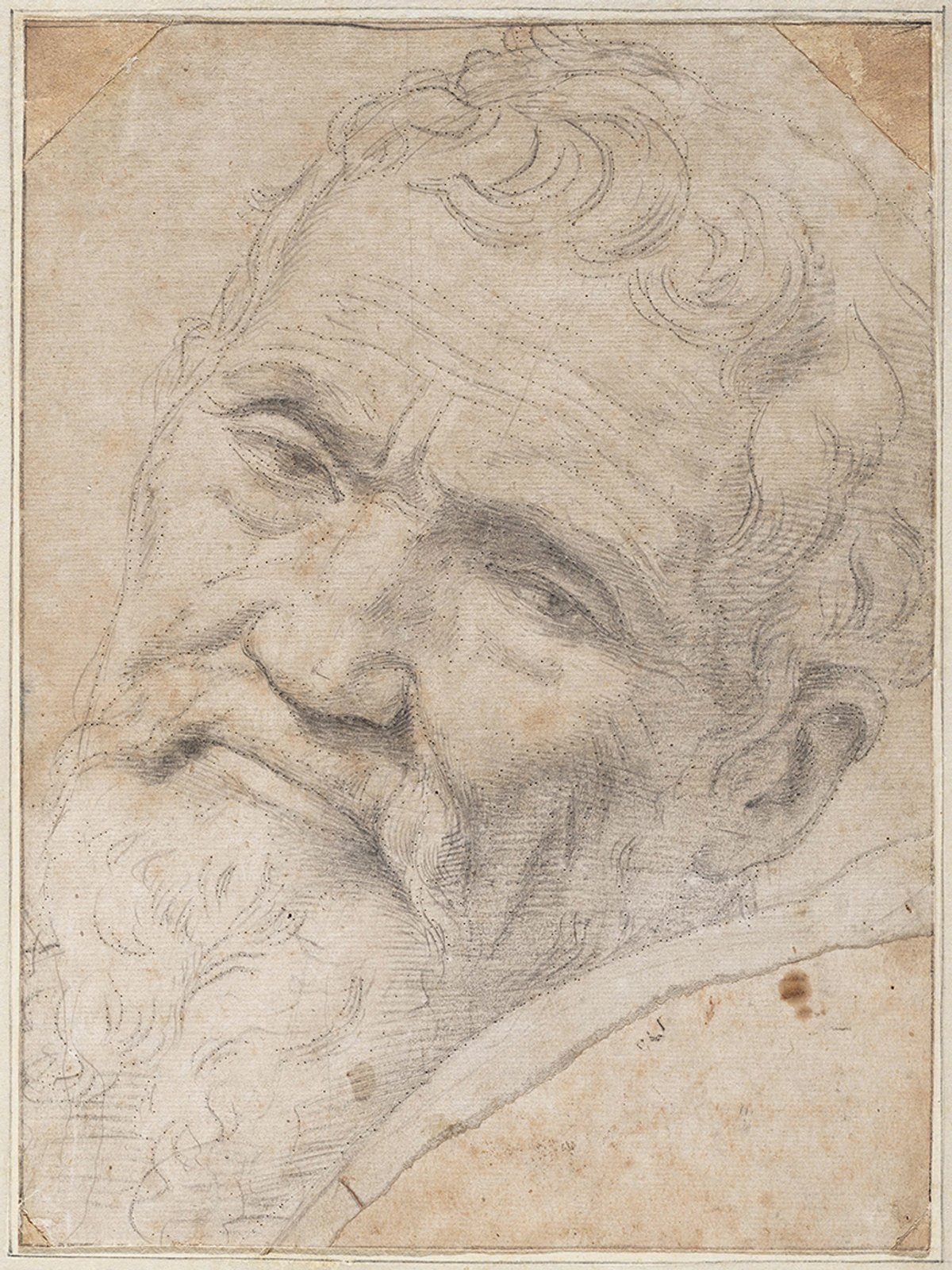

The tension in the exhibition will be between Michelangelo’s inner anguish, which will culminate in his very late drawings of the crucifixion, and his outward-reaching ties to a few close friends and collaborators. These aspects will come together in the show’s opening work—a portrait of the artist by his fellow Tuscan, Daniele da Volterra. On loan from the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the drawing is anything but idealised, with Michelangelo’s famously flattened nose, broken in a fight when he was a teenager, serving as the focal point for an image that suggests both turmoil and taciturnity.

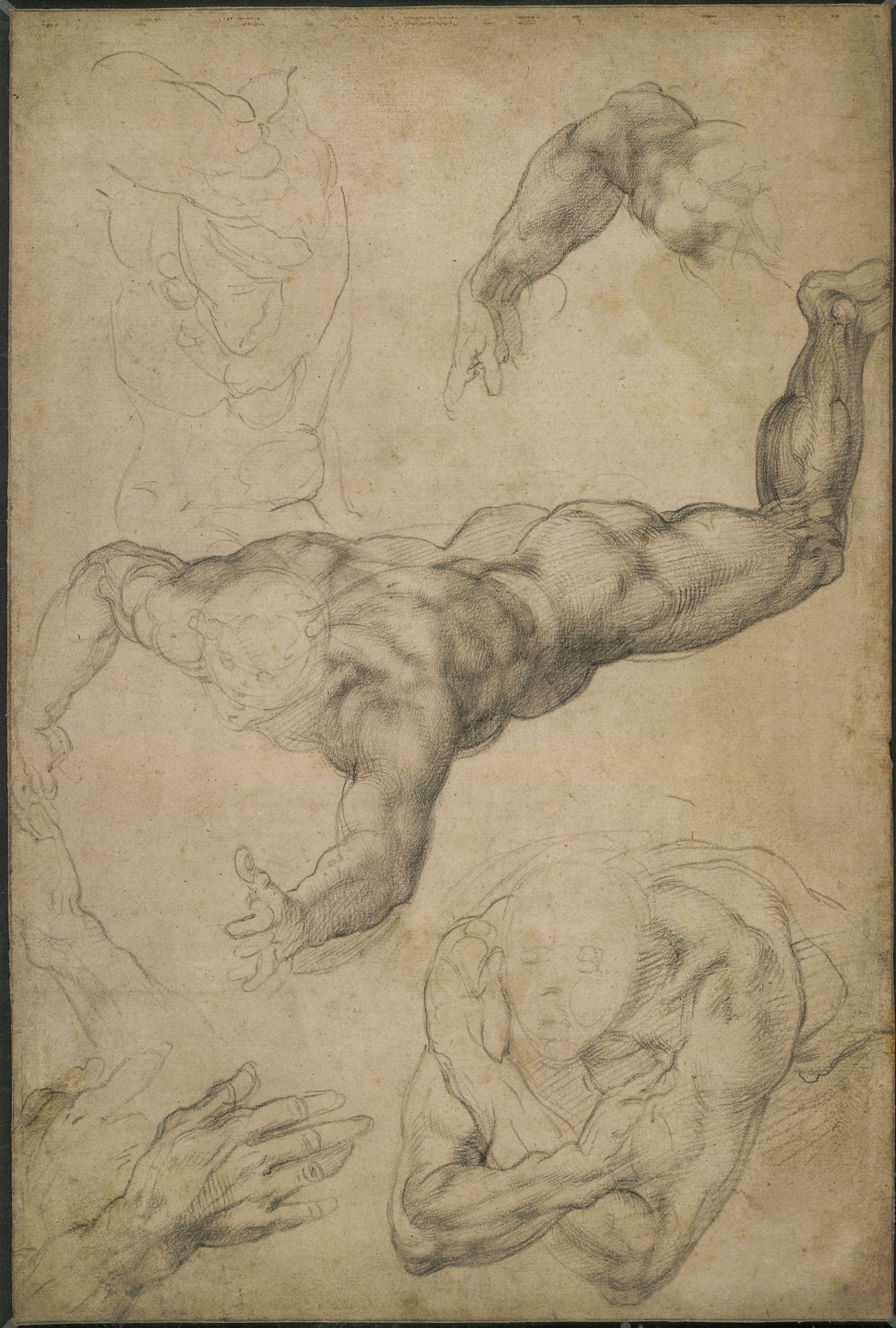

Michelangelo's Study of an angel and other figures for the Last Judgement (around 1534-36) © The Trustees of the British Museum

This early section will summon up The Last Judgment with preparatory drawings and a large colour projection of the complete fresco. Works such as Study of an angel and other figures for the Last Judgement might suggest something sexual in their frank depictions of male beauty. But the show’s curator Sarah Vowles says “that’s not what’s going on there”. She says the fresco, whose numerous male nudes scandalised 16th-century clergy, treats “the human body as the work of God”, not as something “explicitly made to excite desire”.

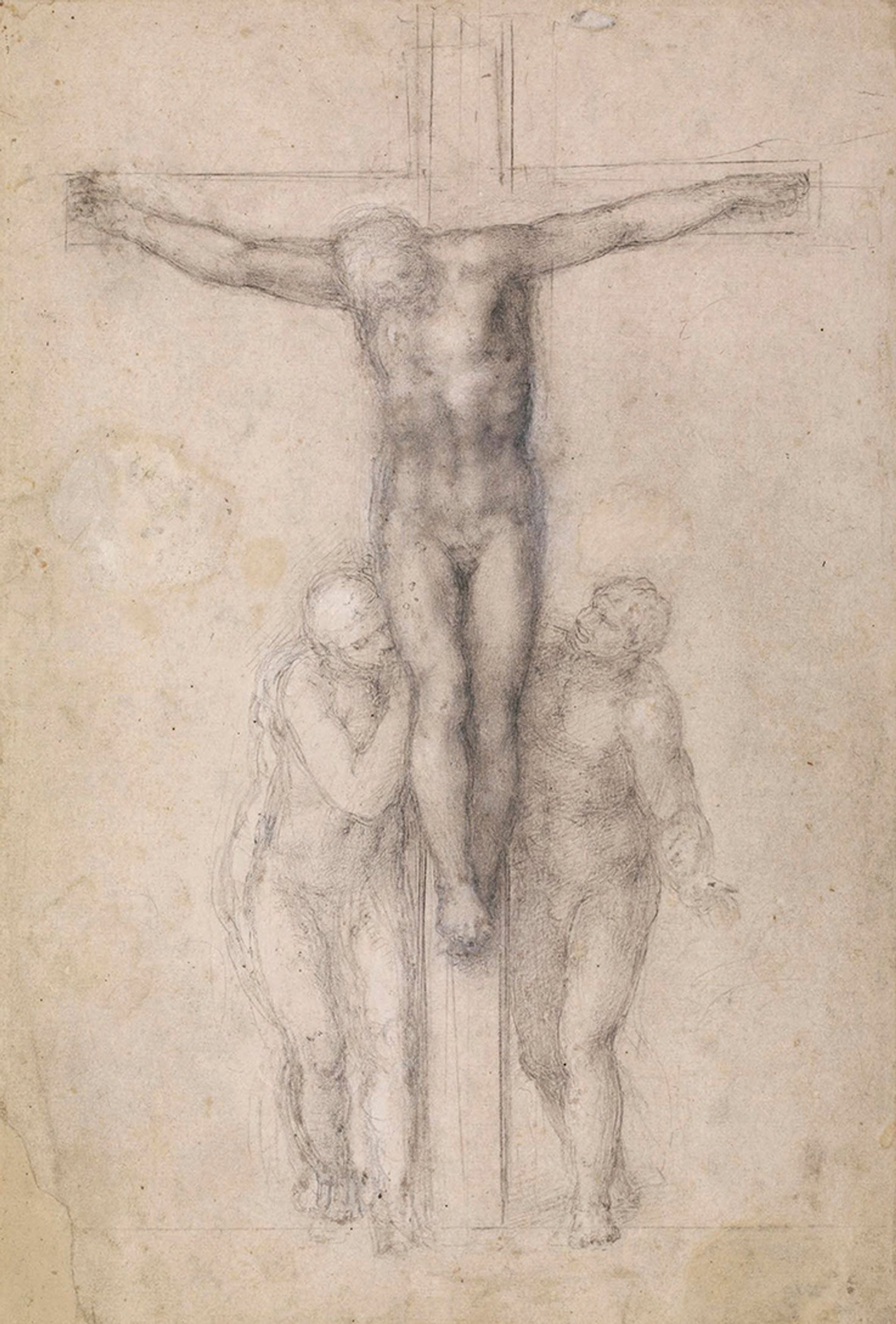

The show will also consider Michelangelo’s emphatic attachment to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, the beautiful Italian nobleman who met the artist in the early 1530s. (Though decidedly romantic, and even obsessional, Michelangelo’s love for him was probably unconsummated, Vowles says.) And the organisers have structured a whole section around Michelangelo’s more spiritual friendship with another highborn figure: the poet and noblewoman Vittoria Colonna. Here, the curators make use of a British Museum masterpiece, Christ on the Cross (1538-41), a sublime devotional drawing made for Colonna. The many monochromatic drawings will be countered with colourful, collaborative paintings, like Marcello Venusti’s The Cleansing of the Temple (around 1550-55), based on a composition by the master. The show will include three Michelangelo drawings that develop the Christ figure.

Marcello Venusti's The Purification of the Temple (around 1550-55) is based a composition by Michelangelo © The National Gallery; London

Michelangelo’s late architectural commissions really “weighed down on him”, Vowles says. Not long after returning to Rome, he reconfigured the Palazzo Farnese, originally designed by another Tuscan, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. By adding an extra storey and a deep distinctive cornice, he created what became the most influential iteration of a High Renaissance palace. The building is represented in the show with an exquisite window study on loan from Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum. Meanwhile, Michelangelo’s work on St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, which lasted decades and only came to fruition after his death, is represented with another Teylers drawing, Studies for the dome and lantern of St Peter’s.

As he became older and more infirm, Michelangelo was increasingly drawn to the image of Christ on the cross. Some of his best known, most admired, and possibly least understood drawings are these crucifixion works on paper from his last years. Remarkably, six of them will be included in the show, including two on loan from the British Royal Collection. Scholars are still working on interpretations of them.

Michelangelo’s Crucifixion between the Virgin and St John (around 1555-64, above right) is one of several depictions of Christ on show

© Trustees of the British Museum

Colonna herself was part of a circle of reform-minded Christians, some of whom were investigated by the Inquisition. Michelangelo’s increasing fascination with salvation through grace has led some to wonder if there might be a tinge of Protestantism in his beliefs, including in these crucifixions, which are deeply meditative and intensely private. “Michelangelo for me wasn’t a Protestant,” Vowles says. Though the late drawings do “use scripture as a springboard for contemplation”, as the new Protestant reformers were emphasising, they do not negate the artist’s mass-going, or attention to the sacraments. Besides,” she adds, “he is working for the Pope.”

• Michelangelo: the Last Decades, British Museum, London, 2 May-28 July