Seven years ago, the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice held the exhibition Philip Guston and the Poets. This prime example of an uber-gallery—Hauser & Wirth—collaborating with an artist’s estate to create museum-quality results took one step further compared with most previous efforts in this curatorial genre. Namely, the setting. The venerable former Scuola site added huge historical lustre to its subject, effectively turning Guston into an heir apparent, a modern Old Master. Now, with Willem de Kooning and Italy, history repeats itself on the Grand Canal, except with different players.

In short, a Dutch émigré to the US replaces his Polish-born counterpart, while The Willem de Kooning Foundation supplants Hauser & Wirth. Regardless, the show of 78 works, including numerous sculptures and drawings, is studded with masterpieces. It is a perfect spectacle for Venice in a Biennale year. Ironies lurk nevertheless, especially given that the 2017 exhibition emerges as a precursor or formula for the present one.

A mix of scholarly mismatch versus magnificent artworks

Italy played a much larger role in Guston’s imagination than it did for de Kooning. Perhaps even insofar as “Guston and Italy” might have been the former show’s premise, whereas the latter could be considered as “De Kooning and the Old Masters”. Indeed, there’s the rub. De Kooning was a Northerner to the depths of his soul. Despite the curators’ thesis, the artist’s two Italian sojourns (in 1959 and 1969) look more like dolce vita interludes than they do major artistic watersheds. In any case, it was common for many American artists and writers to visit or live in Rome during the 1950s.

According to the Italian painter Piero Dorazio, “Rome was like Paris, it had become the navel of art in Europe.” Contradicting the curators’ wishful ambitions, de Kooning’s contemporary Esteban Vicente recalled the artist saying he “didn’t like” Rome. In fact, “Rothko and Italy” would yield a better art historical plan. Tellingly, banners on the Accademia’s façade and the introductory wall’s signage read “Willem de Kooning Italia”. This does not translate exactly as the catalogue’s “Willem de Kooning and Italy”. Such a minor detail points to larger quirks.

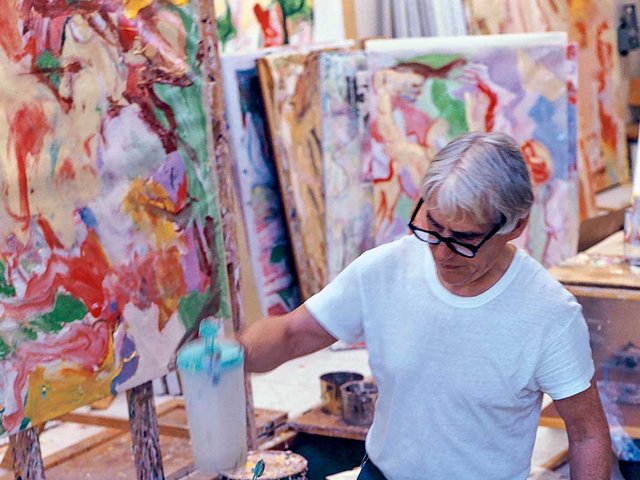

De Kooning's sculpture Clamdigger (1972) in front of Bolton Landing (1957) and Brown Derby Road (1958) Photo: Matteo de Fina; 2024. © 2024 The Willem de Kooning Foundation; SIAE

For example, near the start a trio of “abstract parkway landscapes” hang together for the first time: how do Bolton Landing (1957), Detour (1958) and Brown Derby Road (1958) relate to Italy? They do not. The compositions are manifest paeans to Manhattan’s rural environs. Fast as hell in feel, the sweeping brushstrokes reflect de Kooning’s words to David Sylvester: “landscapes and highways and sensations of that, outside the city—with the feeling of going to the city or coming from it.” This is no speedboat ride from Venice airport to La Serenissima or the Lido. Rather, it is the glimpses that slip by someone travelling in a car streaking through America’s autopia.

Still, the paintings themselves remain stunners. On a facing wall stands another terrific pictorial grouping, from 1960: Villa Borghese, A Tree in Naples and Door to the River. Again, unlike Venice and Naples, Long Island has umpteen rivers, creeks and estuaries, while many a house’s door there opens onto them (Rome turns its back on the Tiber). Nor do Neapolitan trees evince the blueness saturating the relevant canvas. (One guess is that, true to the wordplay for which de Kooning was famous, he conflated the popular 1945 film A Tree Grows in Brooklyn with the colour Naples Blue). Likewise, digging for clams, embodied by the imposing hominoid Clamdigger (1972)—in the same space and gnarled as an old crustacean—is more an American than Italian habit. The sole transatlantic link that springs to mind stems from the wrong realm, spaghetti alle vongole. Delicious but not de Kooning.

A mix of scholarly mismatch versus magnificent artworks

This mix of scholarly mismatch versus magnificent artworks lingers throughout the whole display. In particular, an ensuing suite of oils and collages on paper, collectively known as the Rome series because they were made there, highlight how de Kooning’s change in style starting around 1957, from congested imagery to broader vectors, has scant relevance to any Italian connection, let alone the “profound impact” that the press release proposes. The awkward truth is that the literature has long and correctly ascribed this shift into angular forms (in the oils) and monochrome (in the drawings) to the influence of de Kooning’s self-proclaimed “best friend” and inveterate New Yorker, Franz Kline.

De Kooning's Untitled (Rome) (1959) © The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society, NY

Along similar lines yet from a personal standpoint, it was impossible not to restrain a smile at the very first piece, the sculpture Hostess (1973), located by itself in a de facto lobby preceding the main spaces. What amused was the co-curator Gary Garrels’s claim that the sculptures tend to be “overlooked”. On the contrary, they had a titular place and an essay to themselves in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s touring retrospective of de Kooning as long ago as 1983. A decade earlier the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis devoted an entire show to the drawings and sculptures, and subsequently Matthew Marks Gallery published an illustrated checklist of the complete sculptures in 1996. Most recently, the massive 2011 survey at New York’s Museum of Modern Art included all 13 Untitled sculptures that de Kooning modelled in 1969 and which reappear here.

I was flattered to see Hostess play an identical role to that assigned to her at the very beginning of an exhibition—Abstract Expressionism: A World Elsewhere—that I curated in 2008 for Haunch of Venison in New York. Like Cindy Sherman’s photographic take on this staple Upper East Side figure, de Kooning’s wonky woman is hilarous, one axis in Abstract Expressionism’s extremes running from the ridiculous to the sublime.

Such polarities dominate the final four of the seven rooms. Violence and metamorphosis rise upfront in the various tortured heads, a crucifixion drawing and a small yet superb female personage, rendered in oil and charcoal, which resembles a hideously spatchcocked chicken. In contrast, a seraphic mildness marks the last paintings, as though de Kooning had achieved a state that transcended the grotesque, the acutely colourful and carnivalesque that shocks and shudders elsewhere in these later years and is brilliantly condensed in the present selection.

Where have we seen these extreme moods before? Hardly in Italy, with its yen for classical ideals and harmony. The answer lies in de Kooning’s watery homeland and its past—notably the Netherlandish Old Masters Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel with their images of torment, earthly delights, comic elements, fallenness and sheer fleshiness. After all, when de Kooning sent the epochal Excavation to the 25th Venice Biennale in 1950, under a magazine on his painting table lay a reproduction of Bruegel’s Triumph of Death (1562-63).

Though De Kooning and Italy gets its ideological geographic compass wrong, it still packs a big visual punch.

What the other critics said

So far, the exhibition has garnered high praise, if not altogether informed reviews. In Artforum Travis Jeppesen found an unsurprising surprise that “the real revelations here are the sculptures, which range from the balletic to the turdlike”. For Apollo,Charles Darwent pondered “how Italy remade Willem de Kooning”. Laura Freeman in The Sunday Times judged the show to be “an exhilarating five-star knockout”. And Alastair Sooke in The Telegraph deemed the show “an immaculately curated, dazzling tour de force, with satisfying bronze sculptures that appear as squidgy as mozzarella, paintings of carpaccio-coloured, spread-eagled figures, and gelato-coloured abstract canvases of phenomenal power”.

• Willem de Kooning and Italy, Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice, until 15 September

• Curators: Gary Garrels and Mario Codognato