Mario Piana, the Proto (architect) responsible for the maintenance of St Mark’s Basilica, in Venice, has warned that the city’s historic building stock is crumbling from the bottom up because of the rising water level of the lagoon.

In an interview, Piana, who has 40 years’ experience working with Venice’s buildings, says that the iron tie-rods connecting the heavy stabilising floors to the thin walls—designed to weigh as little as possible on the shifting ground of the lagoon—are rusting and breaking inside the walls because of the damp that is rising many metres up the buildings.

Piana has some model, low-cost, solutions to the problem, but these cannot be more than stop-gaps while a method of preventing the chronic rise in the water level is designed and implemented. This requires concerted political will, in both Venice and Italy, and massive associated investment, as well as the preserving and sharing of fast-vanishing special building skills that used to be passed down from generation to generation.

Piana, 72, knows them all, as well as the materials used. He understands intimately how hostile the environment has become to the city. After a distinguished career at the elite Venetian architectural university (IUAV) and practising as a conservation architect, he was appointed in 2016 to the prestigious but demanding post of Proto to the near-1,000-year-old St Mark’s Basilica.

The basilica is in the lowest-lying part of Venice, which floods long before the mobile barriers, called Mose, between the sea and the lagoon are closed, a policy which was adopted in order to interfere as little as possible with the shipping entering the commercial port inside the lagoon. Piana tired of seeing his glorious church, which gleams inside with precious gold mosaics, being inundated over 100 times a year, so he took the decision to put a glass barrier around its façade, which has successfully protected it since 2022. Now he wants to install more barriers at the back of the basilica, but money is scarce. He says, “St Mark’s needs constant maintenance and it has no assets of its own because it does not charge for entrance to the basilica itself, just the museum part and the bell tower, and that does not bring in enough.”

Mario Piana has written down all he has learnt over 40 years in Costruire Venezia (Building Venice) (Marsilio Arte, 2023). It is indispensable to anyone restoring a Venetian building. But it is also an implicit warning: do not think that because a city has stood for hundreds of years that it will continue to do so.

Piana is a sceptical man of few words, too used to seeing his city abused and neglected, but he agreed to speak to us about the situation today.

Enrico Tantucci: What is the key moment for the buildings of Venice?

Mario Piana: The key centuries are the 15th and 16th, when the architectural language of the Renaissance and classicism is adopted and the white Istrian stone gets used instead of wood, the opposite of what was practiced previously, when the lightest possible materials were chosen. This change was inevitably going to cause stability problems in the long run, so the tie-rods were introduced to ensure that the buildings stayed upright.

When did the stability of Venetian buildings begin to be threatened?

At the beginning of the 20th century, when people began to heat their houses. The wide discrepancy between internal and external temperatures gradually resulted in the deterioration of the tie-rods and the structural failures that we begin to see, with the lower walls of so many buildings bulging outwards.

Replacing the tie-rods is a first step, but it is not enough, because there is also the capillary rise of brackish water within the walls, which, as it evaporates, deposits impressive amounts of salt in the brickwork. Thus bricks, stone, mortar and plaster are disintegrating and the damage reaches up to, or beyond, the first floors of the buildings. The Mose barriers now defend the city from the worst of the episodic flooding events, but we have the ever more serious problem of the chronically rising sea level, which makes the moisture in the brickwork even worse. And over the past 100 years a whole building culture has disappeared because the use of reinforced concrete has been imposed.

How can rising damp in Venetian houses be countered?

By creating horizontal barriers across the brickwork, but it is very expensive and this is a city where people are moving away because they can’t even afford to buy a house. Yet there would be cheaper ways to intervene on static and damp problems.

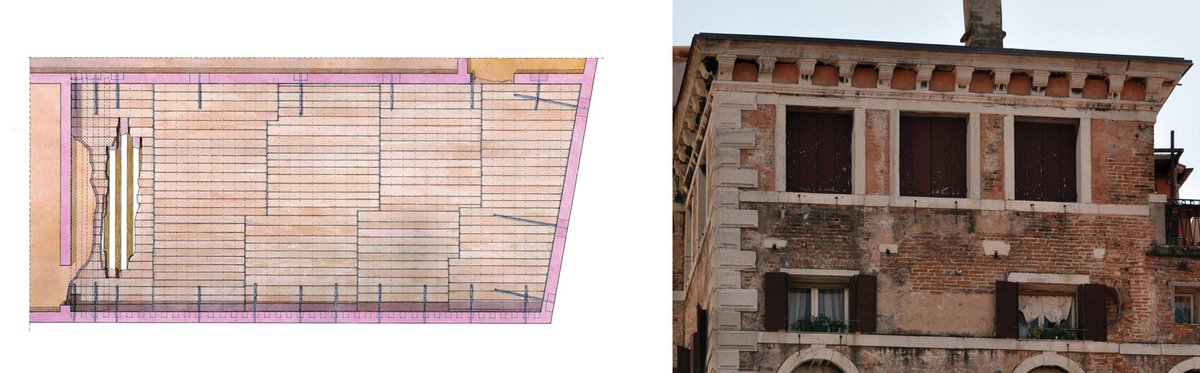

I am thinking of the project, financed around 2005 by the British Venice in Peril Fund and under my direction, to conserve and turn a publicly owned, working-class house into four flats.Before intervening in its structural and damp problems, we researched its history in detail so as to understand the precise causes of the deterioration. In this way we adopted solutions that respected its integrity and cost much less than modern methods.

You highlight another serious problem for the future: Venice is not just losing its residents but also the skilled workforce capable of maintaining the buildings.

The carpenters, the blacksmiths, the craftsmen who can restore or lay a traditional terrazzo floor using flexible lime and not rigid cement are disappearing. The current workforce comes mainly from Eastern Europe and has to train in the field because there is a shortage of professionals who can pass on the traditional ways of working on the very delicate building fabric of Venice.