The wildly productive period that Jean-Michel Basquiat spent from 1982 to 1984 living in Los Angeles, including at Larry Gagosian’s house on Market Street in the Venice neighbourhood, is an important but often minimised part of his evolution as an artist. This chapter made headlines in 2022 when 25 paintings he supposedly made during this period debuted at the Orlando Museum of Art, only to be seized by the FBI as suspected forgeries. Now, showing what Basquiat was really making during this time, Larry Gagosian has teamed up with longtime colleague Fred Hoffman to co-curate a survey of the artist’s Los Angeles work, Jean-Michel Basquiat: Made on Market Street (7 March-1 June), at Gagosian Beverly Hills.

Gagosian stresses that his exhibition was not organised as a response to the Orlando fiasco, in which the museum’s then director claimed that the artist had created a series of works at Gagosian’s house and sold them directly to the screenwriter Thad Mumford. “The intention of our show is not to refute that crackpot story,” he says. “That was just a complete fabrication. This idea that he was selling paintings out the back door while living with me is complete bullshit. He was a very honourable artist.”

Curatorial scavenger hunt

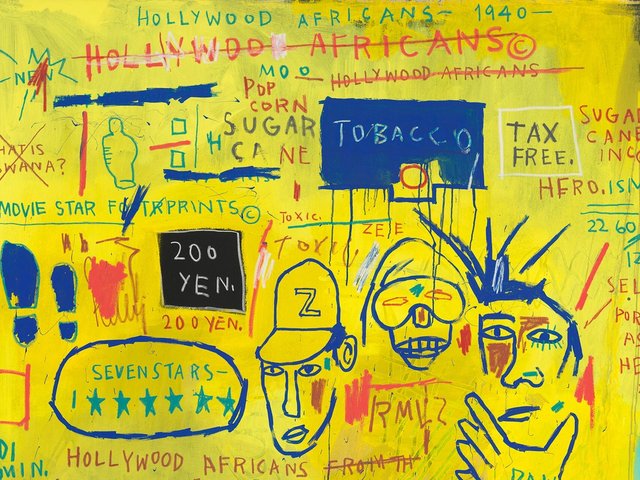

Rather, Gagosian says his intent was to recreate his gallery’s second show with Basquiat, which featured “this incredible, powerful wall of seven paintings”, including Hollywood Africans and Museum Security, but it was not feasible. “I couldn’t get the loans I wanted—some people were unwilling to lend and in some cases I couldn’t even figure out where the works are.” His goal shifted to reuniting works the artist made on Market Street, including Hollywood Africans, now owned by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

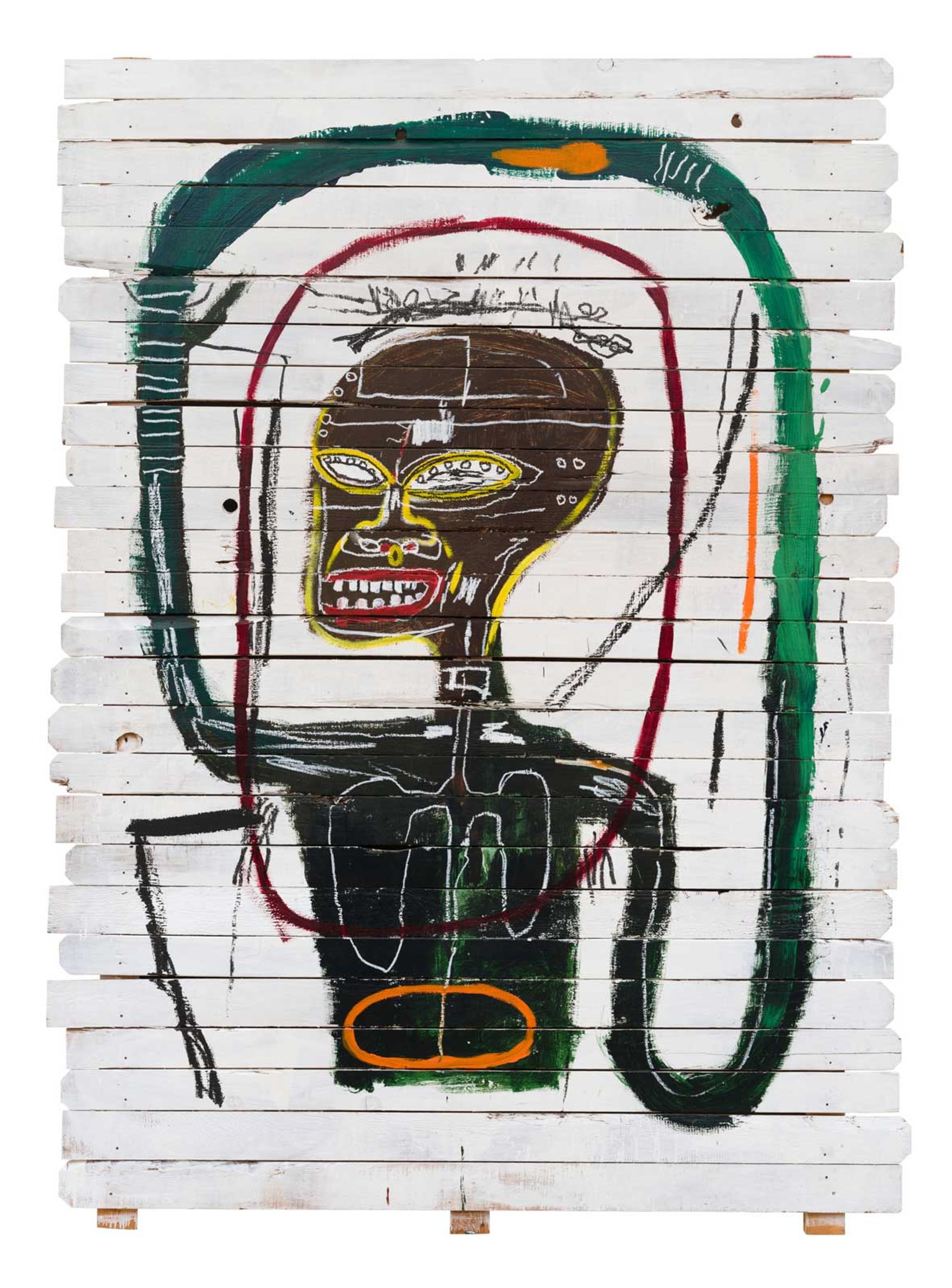

Jean-Michel Basquiat painted Flexible (1984) on wooden fencing taken from behind his studio

Photo: Jeff McLane, © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York; Courtesy of Gagosian

Of the 30 works in the show, only a handful are for sale, says the dealer. “In historical shows like this, there are usually three categories. There are a few for sale. Then there are works that will never be for sale, either because collectors will never sell or because they’re owned by the Whitney or MoMA. Then there’s the grey area, where if they get a great offer, a collector might be willing to sell.”

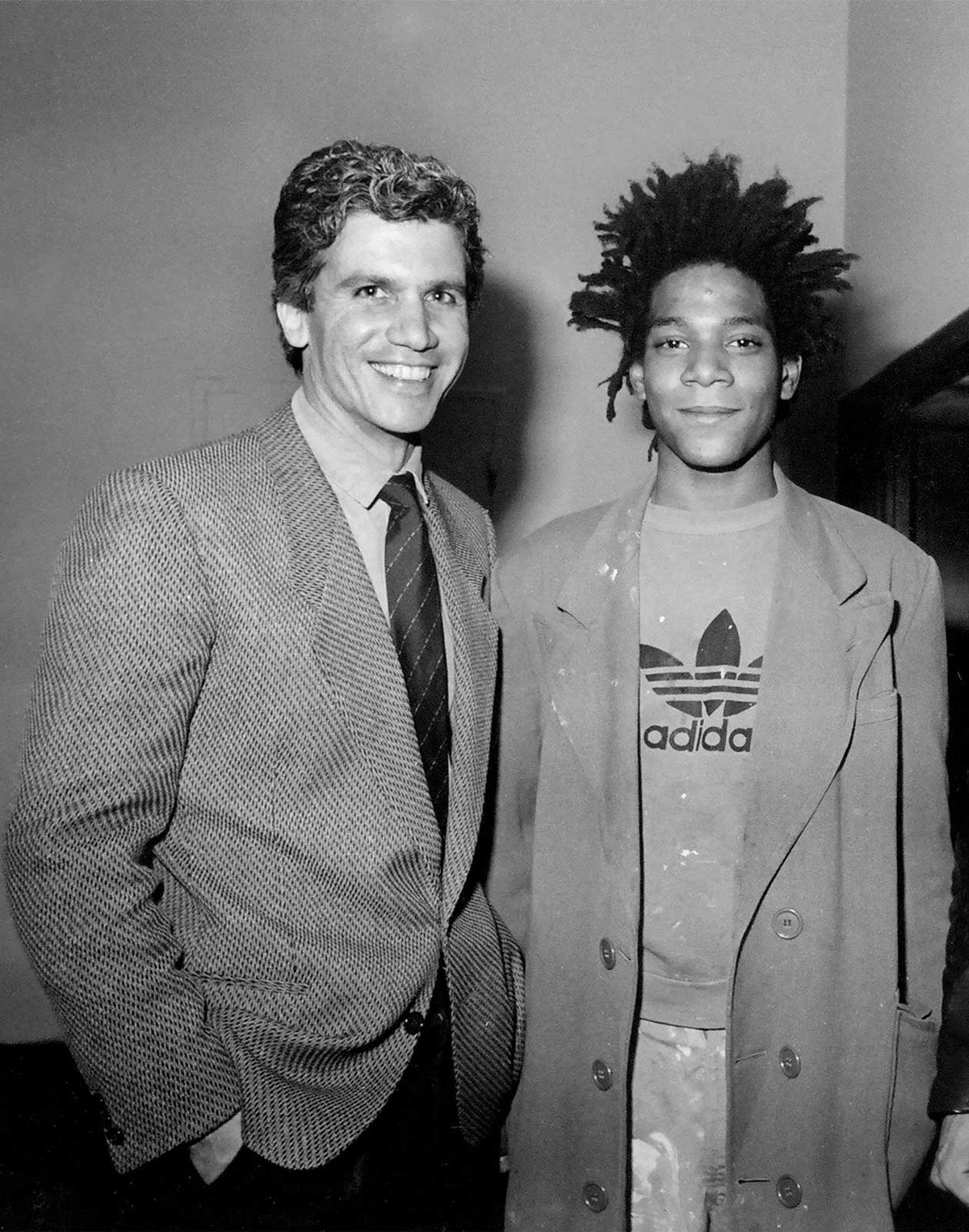

Gagosian’s relationship with Basquiat began in New York in 1981, when Barbara Kruger invited him to see a group show featuring her work at Annina Nosei Gallery called Public Address. “Barbara’s been a good friend of mine for many years,” Gagosian says. “I didn’t know that Basquiat was in the show—in fact I had never heard his name before.”

His reaction was intense: “For lack of a better word, it was just electrifying. I just knew immediately this was a major talent,” he says. Within a few days he had bought three paintings for a total $9,000. That led to the 1982 and 1983 shows at Gagosian in Los Angeles and an invitation to stay at his three-storey home on Market Street near the beach, where there was a lofty, ground-level space that Basquiat used as a studio when he was not out partying.

In 1983 Basquiat came back to Los Angeles, this time working out of a studio a few doors down while staying at the L’Ermitage hotel. As the story goes, the artist discovered an unhoused person sleeping in the small courtyard behind the studio, and decided to remove the wooden fencing to return the area to the city in a way. He took the wood into the studio to paint on, resulting in important works such as Gold Griot, Flexible and M. The first two were shown in the Brooklyn Museum’s 2005 Basquiat survey, but this is the first time all three will be seen together, according to Hoffman.

He believes that Basquiat’s Los Angeles works offer an important alternative to the myth of Basquiat as a creative savant or a co-opted street artist. “Because the New York art intelligentsia tried to single-handedly identify him with downtown street culture, they overlooked the fact that he was first and foremost a painter who was a part of an important lineage of modern artists,” Hoffman says. One point of inspiration was Robert Rauschenberg; Hoffman introduced the two when Rauschenberg was working in Los Angeles.

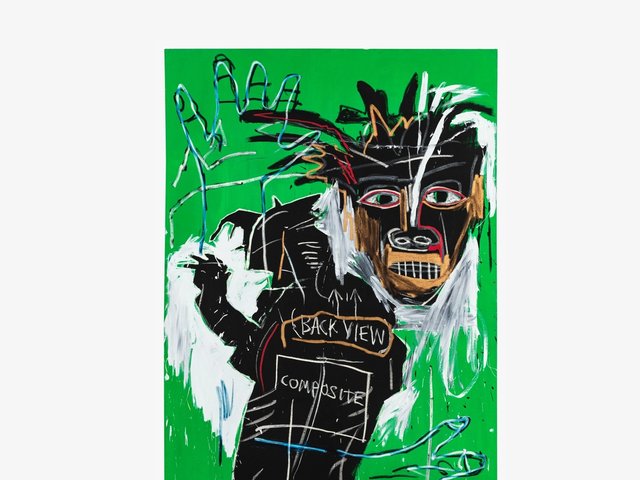

Having just founded New City Editions, Hoffman helped Basquiat make six editioned works, including the monumental Tuxedo, included in the new show. Over eight feet tall and topped by one of Basquiat’s signature three-pointed crowns, it was “extraordinarily ambitious”, says Hoffman, describing a silkscreening process that involved photographing 15 original drawings and one collage and reversing the images so black becomes white and vice versa, before printing. “It took four printers, two on each side, to even pull the squeegees,” he says. “It was a very complicated work.”

Tuxedo is also complex thematically, evoking the experiences of a Black man in a white world. Hoffman also sees a direct connection to the rise of hip-hop culture in the way Tuxedo samples snippets of texts and symbols. “He spent a lot of time with some of the key figures in the hip-hop scene and that’s an important part of his LA experience,” the curator says. “He wanted to create a visual equivalent to the culture he was a part of.”