What to do when a neighbourhood is about to be transformed by light rail, bringing the blessings of convenience and mass transportation but also the bane of gentrification and higher prices? A major urban project in South Central Los Angeles is using public art—murals and sculpture—to try to keep a traditionally Black neighbourhood knitted together, by reminding people of past accomplishments and shared histories and laying the ground for those yet to come.

Destination Crenshaw is billed as the largest Black public art project in the US, stretching 1.3 miles along Crenshaw Boulevard, with a dozen outdoor works already announced and more to come. These will include pieces by renowned artists including Charles Dickson, Melvin Edwards, Maren Hassinger, Artis Lane, Alison Saar, Kehinde Wiley and Brenna Youngblood, as well as local muralists. After some delays, its first commissions will be unveiled this spring.

Rendering of Kehinde Wiley’s sculpture, Sankofa Park Courtesy of Destination Crenshaw

The idea came about a decade ago, says Marqueece Harris-Dawson, the Los Angeles City Council representative for District 8, which includes the Crenshaw area. “When construction on the Crenshaw light rail was about to begin, voters were very concerned about the impact it was going to have on the neighbourhood,” he says. “We reached out to activists, artists, business owners, residents and faith leaders to ask what we should do about this, because the community needs the rail line, but we don’t want to lose our community in the process.”

Some suggested building a museum around the light rail, he says, “so that people who get on or off that train understand where they are—what the history is, who’s been there, who is there now, who’s going to be there going forward.” The idea evolved into an outdoor museum, geographically focused on the section of Crenshaw Boulevard between two Metro stops, Leimert Park and Hyde Park, where the train runs above ground. Harris-Dawson sees it as a model for community “placekeeping”, rather than placemaking.

The non-profit Destination Crenshaw was set up to organise and fundraise for the project. Initial financing was private, with subsequent funding from Metro, the Getty Foundation, city, county and state sources bringing supporting an expected project cost of $122m through 2027.

Joy Simmons, a long-time local resident and art collector, was appointed to be the project’s senior art and exhibition adviser, and she worked with a committee to select the artists to receive commissions. That committee included such people as Naima Keith, then the chief curator of the California African American Museum (and now the vice president of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), as well as Ron Finley, a grassroots activist. “The team put together a list; they all recommended artists,” Simmons says. In addition to having relevant experience, the artists had to be from Los Angeles, have been educated here or have worked here—and, most importantly, she says, “have a connection to the community”.

Generally, the works reflect a positive mindset, Simmons says, “because they know we live here. They know that there are four or five schools all around the corridor. So I think that had an impact on how artists decided what types of work they wanted to present.”

So far, 12 artists or artist groups have been commissioned to make work for Sankofa Park, a new public space at the northern end of the project, and several “pocket parks” and wall spaces. Landscaping is part of the project, and is designed by Studio-MLA, working with the project architect Perkins&Will. Sankofa Park will include commissioned sculptures by Wiley, Hassinger, Dickson and Lane.

“Destination Crenshaw reached out in August 2018 and invited me to create a permanent outdoor bronze sculpture for Sankofa Park,” says Wiley, who is now based in New York but grew up in this neighbourhood. “My childhood in South Central Los Angeles gave me a foundational perspective through which I view American cultural, racial and political patterns and dynamics, both within the country and abroad.”

His 27ft-tall sculpture, Female Warrior, subverts the European tradition of white male heroes on horseback and features a young, West African woman her head turned to look back, while her horse starts to rear up. “The rider functions as an intervention that embraces the past and the myriad historical means of propagandising state power,” says Wiley, “and it also subverts that agenda by intentionally advancing a broader, more inclusive worldview.”

Another artist with personal attachments to the area is Alison Saar, whose mother is the celebrated artist Betye Saar. “When I was really little, Crenshaw and Leimert Park were really a big part of my mother’s life,” she says. “When we were living in the South Bay, which was largely white, coming up to Leimert Park and Crenshaw was a way for her to connect with her community.”

Saar recalls that in the 1960s the area became an important gathering place for Black artists and musicians; the influential Brockman Gallery, which showed many contemporary African American artists, was located there. Saar applied to the Destination Crenshaw project because of those memories and “loving this idea that it would be a sculpture garden in a historically Black neighbourhood”.

Sankofa Park (shown rendered), which will also feature works by Charles Dickson, Maren Hassinger and Artis Lane. Works by artists including Alison Saar and others will be located elsewhere in the area Rendering by Perkins & Will; courtesy of Destination Crenshaw

Saar’s contribution, Bearing Witness, is composed of two 13ft-tall bronze figures, a man and a woman, facing one another. Their piled hair will be full of objects such as books and musical instruments that reflect the rich culture of the area.

Making room for murals

As a dispersed city that most people see while driving, Los Angeles has had an important tradition of murals that celebrate local heroes and events. In keeping with that lineage, Destination Crenshaw has found both public and private spaces to place a number of murals. One on the side of an auto parts store will be by the veteran muralist Patrick Henry Johnson. He is familiar with the neighbourhood and 12 years ago he painted a mural near the intersection of Crenshaw and Stocker called The Elixir.

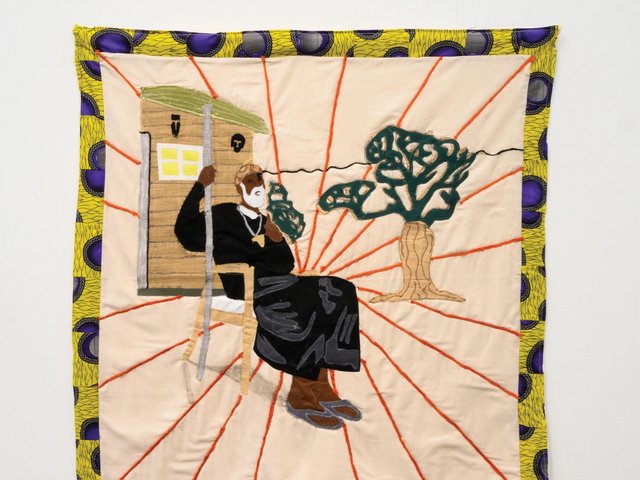

When Johnson found out about Destination Crenshaw, he felt compelled to put in a proposal. He won a commission, for a wall near the corner of 57th Street and Crenshaw; his assignment was to pay tribute to Paul Revere Williams (1894-1980), a celebrated Black architect whom he knew nothing about when he started. However, the more research he did, the more he grew to admire the man who created elegant residences for the stars (including Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra), as well as distinctive public buildings, including the First African Methodist Episcopal Church and Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills.

My childhood in South Central Los Angeles gave me a foundational perspectiveKehinde Wiley, artist

In Johnson’s design, Paul Revere Williams, The Pawn Who Became King, Williams strides forward while several of his most famous buildings appear around him—from the parabolic La Concha Motel in Las Vegas to the futuristic Theme Building at Los Angeles Airport.

Work on the mural and installation of the sculptures have been delayed due to the torrential rains that pelted the city in early February. However, when spring comes Johnson will be up on scaffolding working on the mural himself, with one or two assistants. “I’ll start with a nine-inch roller,” he says, “then five-inch brushes, then four-inch, then ultimately, you’re down to like an inch. That’s when you know you’re about to finish.” He expects to complete the work by early summer.

“There’s no way this momentous art project was going happen in Black Los Angeles without me,” Johnson says. “So whatever twists and turns I’ve had to go through, I don’t mind it all. Once it’s finished, I’ll be part of that legacy.”