Two years on from the last major milestone, the push for representation of art from the far north appears to have reached another. In 2022, the inaugural Sámi pavilion at the Venice Biennale brought to the fore three Sámi artists whose work sought to “defend Sámi perspectives”, according to the curator. At the same event, the Inuk artist Shuvinai Ashoona received a special mention—her playful, fantastical interpretations of modern Arctic life capturing the imagination of the opening ceremony judges.

This month, a more focused, national moment of recognition for Indigenous creativity is taking place. Several exhibitions and events in the UK are bringing to the fore work by leading contemporary artists—Ashoona among them—along with a figure who paved the way for future generations. They make up part of a continued, promising international shift.

Spotlight on a Sámi pioneer

At Tate St Ives, the Sámi artist Outi Pieski is having her first large-scale UK exhibition (opens 10 February). Pieski is from Sápmi, the traditional, borderless territory of the Sámi people that stretches across Norway, Finland, Sweden and Russia. She uses her art to evoke the connections between its human population, the wildlife and the land. Simultaneously, she seeks to preserve Sámi culture in the face of ongoing intrusions into Arctic life.

Outi Pieski's first large-scale UK show opens this month at Tate St Ives

Photo: Teuri Haarla

“In my work I try to embody the Sámi philosophy of soabadit, or positive reciprocity,” she tells The Art Newspaper. “This holistic worldview is crucial for living in the harsh Arctic environment and understanding the region's ecosystems, but historical colonialisation has endangered our knowledge of it.”

Equally important to Pieski is duodji, an ancient form of “collective craftivism”, she says, that connects Sámi people across generations. In her work, duodji appears in various formats—from the vibrant tassels hanging from her semi-abstract landscape paintings to her large-scale, hanging textile installations. These installations—of which one has been made especially for the show—are hand-woven in collaboration with other Sámi craftspeople and incorporate traditional patterning and methods. They are, Pieski says, symbols of healing, and “nomadic monuments that show we are still here”.

Outi Pieski's Guržot ja guovssahat/Spell on You! (2020) is an example of her large-scale textile installations, which she describes as "three-dimensional paintings"

Photo: Sang Tae Kim

Much of Pieski’s work applies to an even wider society. Duodji is historically a women-led tradition, and Pieski describes aspects of her practice, and re-engagement with her ancestral land, as a form of “rematriation”. This is especially evident in her works focused on the ládjogahpir, a horn-shaped hat worn by Sámi women whose use declined in the 1870s after Christian priests banned them, claiming the devil dwelled in their wooden fierras.

Over many years, Pieski worked with the Finnish archaeologist Eeva-Kristiina Nylander to document all of the surviving ládjogahpirs in European collections, and the Tate show will include a photo series, a book and a real-life headdress that brings much of this research together. “In one installation Pieski is essentially looking at physical changes in the shape of this hat as an indicator of not only the suppression of Sámi culture, but of women's rights and freedom of expression,” says Anne Barlow, the director of Tate St Ives.

Pieski, meanwhile, hopes the objects can act as a mediator for debates around repatriation—an issue pertinent to many nations today.

Outi Pieski's 47 eanemus ohccojuvvon máttaráhkut/47 Most Wanted Foremothers (2019) was created in collaboration with Eeva-Kristiina Nylander Installation view courtesy of Minds Rising, Spirits Tuning, The 13th Gwangju Biennale. Photo: Sang Tae Kim

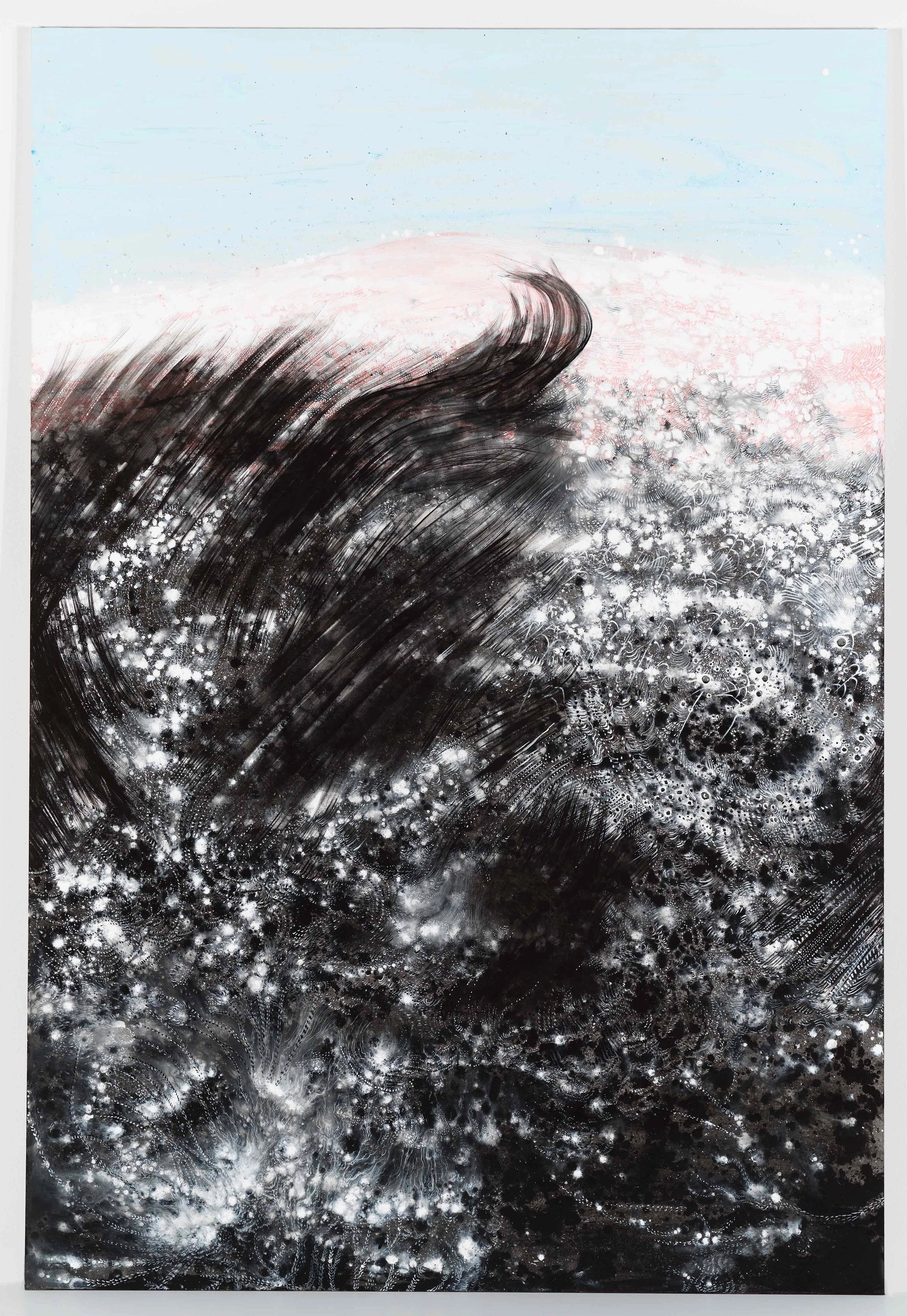

Conversations around Sámi cultural heritage are closely tied to the issues of land, and at Tate other works will address the impact of the extraction of natural resources. This is perhaps most explicit in Pieski’s paintings, such as Iehčanas vuoigatvuohta leat ja lieđđut/Independent Right to Exist and Flourish (2018), which draws its title from the Ecuadorian Constitution provisions of 2008. It depicts, in luminous detail, a mountain, similar to those on which wind farms are being built in Greenland to create so-called “green energy”, yet which are imposing upon Sámi livelihoods negatively in the process. “I'm interested in leading this fight against the industrial land use in our region,” Pieski says. “Our sacred mountains have an inherent right to be themselves without being subjected to the extraction of resources.”

Outi Pieski's Iehčanas vuoigatvuohta leat ja lieđđut/Independent Right to Exist and Flourish (2018)

© Ari Karttunen/EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art

Pieski feels that we are living in “the third wave of the Sámi movement”—the second having taken place in the 1960s and 70s—in which the environment, identity politics, feminism and decolonialism are all deeply intertwined. She hopes her new exhibition, with the brand-new, immersive installation at its heart, will offer a space in which to reflect—and perhaps even have a “bodily experience”.

Inuit artists past and present

Elsewhere, the work of two Inuit artists from different generations are receiving much-deserved attention from disparate institutions.

At the Perimeter in London—the non-profit, private space set up to house the collection of its founder Alex Petalas—Shuvinai Ashoona is having her latest stand-out moment with a solo show of recent drawings (until 26 April). The artist, who is part of an artistic cooperative in Kinngait, in the far east reaches of the Canadian Arctic, merges mythology, humour and pop culture references to create thoroughly unique depictions of ordinary life for Inuits in the region. (Another artist from the Kinngait Studios co-operative, Ningiukulu Teevee, has a show just opened at Canada House, running until 1 June.)

Shuvinai Ashoona's Drawing like the elephant (2023) embodies her playful style

Courtesy Fort Gansevoort, New York

Like Pieski’s, her works address a range of issues affecting her community today, including climate change and the growing influence of Western culture and language, but highlights the nuance within these developments. Many of the drawings, for example, emphasise the leisurely joy that comes with the warmth of summer—and the collective nature of storytelling across cultures. The work of the wider co-operative over the decades is explored on the lower floors.

It is a different—albeit equally witty and incisive—exploration of Inuit art and life that is put forward at John Hansard Gallery in Southampton (opens 10 February), in a survey of the influential Danish-Greenlandic artist Pia Arke, who died tragically young in 2007.

Arke was born in 1958 in Scoresbysund to an Inuk seamstress and a Danish telegraphist, but was “never at ease being either ‘Greenlandic’ or ‘Dane’”, her son Søren tells The Art Newspaper. Instead, she spoke of herself as existing within a “third place” caught between these identities, and sought to use her work to break free of “a binary perception of nationhood”.

Arke’s approach, says Ros Carter, the head of programmes at John Hansard Gallery, can perhaps be best described as an early example of the “artist as researcher”. She dug into archives and often re-purposed material she found to create books—such as Ethno-Aesthetics—and art, highlighting how imagery has been used by colonial powers to map, define and control Nordic Indigenous populations. One of her most famous pieces is Arctic Hysteria (1996), a performance based on an early 20th-century photograph Arke found depicting a naked Inuit woman screaming, suffering from what was positioned as a “mental disorder”—the diagnosis of which today is widely discredited and linked to patriarchal, prejudice discourse of the time. In her performance, Arke is seen crawling nude across a map of Nuugaarsuk Point, in Narsak, a town where she lived for a while as a child, before tearing it to shreds and rearranging the pieces around her—reclaiming, in a sense, the space through the use of her body.

A still from Pia Arke's Arctic Hysteria (1996)

Courtesy and © Pia Arke Estate

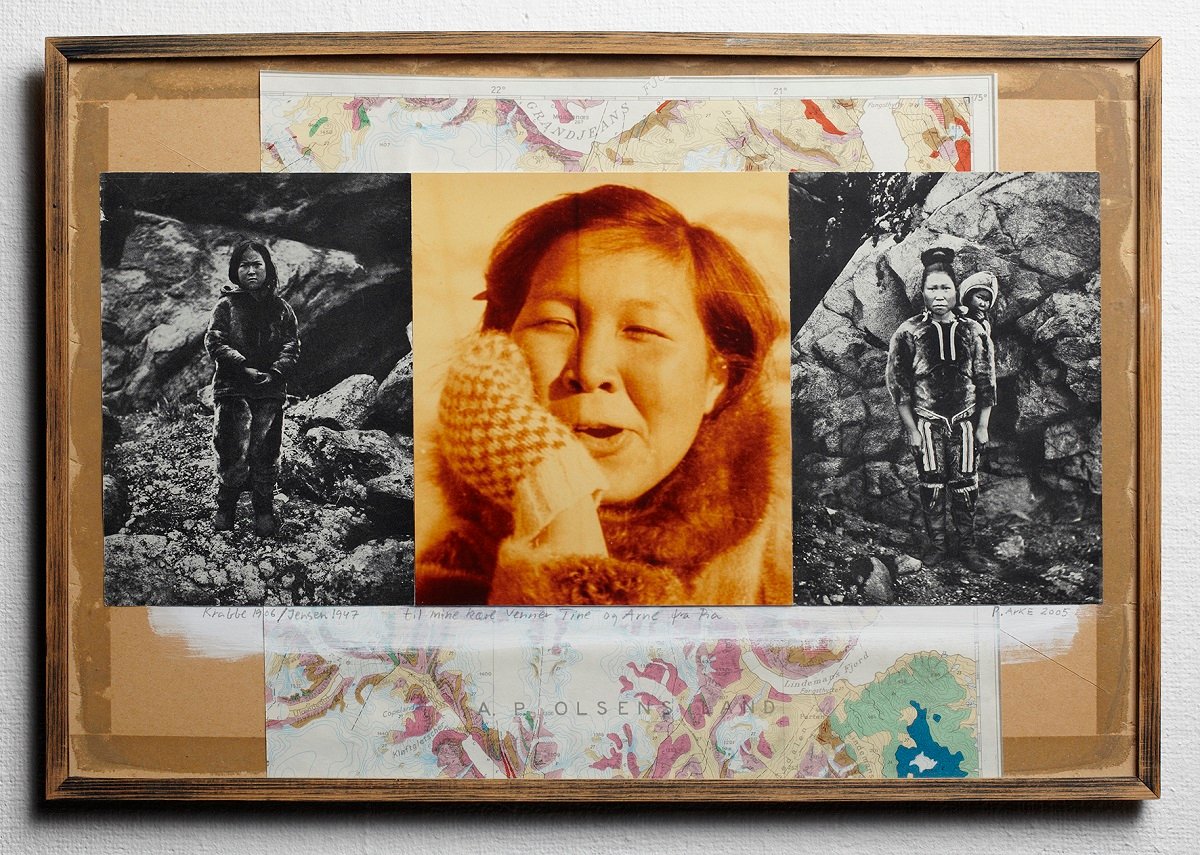

Arctic Hysteria emphasises how “beautifully Arke mixed the personal with the political”, Carter says. Other works in the show do the same: Krabbe 1906/Jensen 1947 (2005) juxtaposes three photographs: one of Arke's mother with a playful expression on her face and two of Greenlandic women posing uncomfortably for the Danish ornithologist Thomas Neergaard Krabbe in 1906. The 1993 work Untitled (Put your kamik on your head so everyone can see where you come from), meanwhile, is a photograph depicting Arke wearing a kamik boot—a traditional form of footwear worn by Inuit women—on her head.

“She doesn’t make overtly political statements, she doesn’t shout,” Carter continues. “It simply feels very human, and she says things quite quietly but powerfully, and with a little bit of a knowing twinkle in the eye.”

Embodying all of that agency are Arke’s camera obscuras, the largest of which has been recreated as the centrepiece of the Southampton exhibition. Visitors will be invited inside the structure, Ros says, to feel the importance of “the process, and the physicality of her work”, says Ros. “It shows how everything with Arke is about the making.”

Power in unity

The exhibitions at Tate St Ives, the Perimeter and John Hansard Gallery come at a time of growing visibility for Sámi and Inuit creativity in Europe and beyond.

This year, for example, Bodø in Norway is Europe's first capital of culture north of the Arctic Circle. To celebrate, more than 1,000 cultural events are being held across the city and wider region, including a special edition of the Kjerringøy Land Art Biennale—opening on 6/7 July—and Sámi Culture Week, which is on now until 11 February.

Over in Venice for the 2024 art biennale, the achievements of 2022 will be built upon with a Greenlandic artist—Inuuteq Storch—representing Denmark for the first time.

Inuuteq Storch is the first Greenlandic artist to represent Denmark at the Venice Biennale Photo: Arny Koor Mogensen, Bolt Lamar

“I think there's a bit of a mood in the air, and there's a bit of a shift going on as well,” Carter says. “There are also artists like Jessie Kleemann, a major Greenlandic artist who is an international name but who has just finally had [a show] at SMK [Statens Museum for Kunst] in Copenhagen.”

It is, many feel, a critical time to be putting these shows on. “Pieski's work deals with really pertinent themes of Indigenous rights, climate change and the impact of industrialisation in the Arctic regions, which makes her first show in the UK feel quite urgent and timely,” Barlow says.

And Pieski herself, while acknowledging Sámi and Inuit culture are unique, also sees the great strength in unity. “Indigenous peoples, societies and the marginalised groups in general, we are small and often don't have much power,” she says. “But when we are allies to each other, we get more power and we can also learn a lot from each other. There can be collaboration, and that’s really important.”

- Outi Pieski, Tate St Ives, 10 February-6 May

- Pia Arke: Silences and Stories, John Hansard’s Gallery, Southampton, 10 February-11 May. A partner exhibition, Pia Arke: Arctic Hysteria, will be shown at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, in summer 2024

- Shuvinai Ashoona: When I Draw, The Perimeter, London, until 26 April

- Ningiukulu Teevee: Stories from Kinngait, Canada House, London, until 1 June