The Art Newspaper was recently given a final tour of Weston, the Sussex house where the pioneering graphic novelist Raymond Briggs lived and worked for six decades—and where he wrote and illustrated beloved classics such as Father Christmas (1973), Fungus the Bogeyman (1977), and The Snowman (1978)—before the contents are packed up and removed so that the house may be sold in the coming months.

This unpretentious building, set a brief incline up from a tree-lined lane, is in the part of Sussex from which the titular Snowman takes weightless flight over the South Downs, the city of Brighton and the south coast of England and beyond, fuelling the dreams of millions of fans of the book, its stage and animated film version and of the smash-hit title song “Walking in the air”. It reveals itself to be an artist-craftsman’s oasis; one just as vividly characterful, colourful and packed with visual delight and unbridled emotion as might be suggested both by Briggs's publications, which brought comic-strip style into books for all ages, and the “grumpy-old-man” persona that Briggs liked to adopt in later life.

One of the prize items is a sheet of paper—in Briggs’s trained calligrapher’s hand, pinned to an internal door with a timeless aplomb suggestive of Martin Luther nailing his Ninety-five Theses on the door of the church at Wittenberg half a millennium ago—that reads in italic capital letters “Raymond is not a normal person”. This particular manifesto had been announced at the family dining table one day by his partner Liz Benjamin's three-year-old granddaughter, Connie Benjamin. “The best compliment I have ever had,” Briggs later said. They were words that he wanted as his epitaph, and which were duly inscribed on his gravestone at East Chiltington, a village a few miles to the east of Weston, following his death in 2022.

Raymond is not a normal person: a young family member's comment that delighted Briggs Leigh Simpson

This placard, and 30 other artworks and pieces of memorabilia chosen from the house at the invitation of the Briggs estate, will be shown from 27 April in the exhibition Bloomin’ Brilliant: The Life and Work of Raymond Briggs at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, a few miles to the north, in conjunction with a touring exhibition from the Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration (Raymond Briggs: A Retrospective) which includes over 100 original paintings and drawings by Briggs.

Pieces from the house that will be on show in Ditchling include artwork for Father Christmas Goes on Holiday (1975), as well as portraits of Briggs's parents, two self-portraits, and illustrations and drafts never previously shown in public.

An artist-craftsman’s oasis: Weston, Briggs's house of 60 years, in an aerial photograph propped up in the house's downstairs sitting room. The two upper windows mark his north-facing studio Leigh Simpson

The house

Briggs bought Weston in 1961, when he was 27, the same year he started teaching at Brighton School of Art, a few miles over the bare, shapely, South Downs. This was also the year he moved professionally from being a prize-winning illustrator of other people's books to being a full blown author-illustrator, starting with Midnight Adventure (1961) and The Strange House (1961). He worked at the Brighton school for 25 years, during which time he married Jean Taprell Clark, in 1963. Jean died a decade later, an event that he later realised inspired the sense of mortality in The Snowman, and Briggs went on to have a happy long-standing partnership with Liz Benjamin. He and Liz came to divide their daily lives between her house five miles to the east, near Plumpton, and Weston itself, which remained the centre of Raymond's daily working life, and home to his studio.

The house has a 1950s feel, with plate glass windows, white-painted timber trim, and is tile hung, in Sussex fashion, on its first floor. It is arranged on two floors, in the “double pile” formation that has been at the core of British country house design since the mid-17th century, with two long, oblong rooms on each floor, with a kitchen, bathrooms and a bedroom leading off them.

A layered vista: Briggs's desk and the view from his studio across the Weald to the North Downs near Caterham Leigh Simpson

The back garden rises gently away from the south side of the house, past a bare-branched, bare-trunked tree that appears to have been pruned over the years into the shape of a handsome goblet. The ground rises more steeply beyond the end of the garden towards the commanding heights of Ditchling Beacon, a focal point on the South Downs Way.

One of the house's first surprises is its view to the north. Surprising because the heights of the beacon to the south give a sense of the house sitting deep in a valley—but from Briggs's writing and drawing desk in his north-facing first-floor studio there is a long, uninterrupted view across the Weald to the North Downs near Caterham. It is one of the layered long-range vistas across the county's three ranges of hill which can catch visitors to Sussex unawares.

Tongue-in-cheek humour: the front door to Briggs's house Leigh Simpson

A sardonic welcome

Briggs's teasing tongue-in-cheek sense of humour, and sardonic attitude to authority and officialese, is signalled even before you enter the house. There are two jokey second-hand warning signs on the front door that read “Beware of the dog: enter at your own risk” and “Attention: electric fence”, for corralling sheep, in seven languages. That appetite for collecting signage of all sorts runs right through the interior, from an Earl's Court sign above the kitchen sink to placards to forgotten medical remedies, to a sign reading "No Vomiting" over a lavatory basin.

Inquisitive plenitude: the ground floor sitting room in Briggs's house. Note the maps pasted on to the ceiling Leigh Simpson

Shelves of memorabilia

The over-riding first impression of the interior is one of inquisitive plenitude. Vivid colours, with inky strong blues and reds; books bursting from shelves; pictures large and small by Briggs and others hung in clusters; well-stuffed sofas and chairs; a self-aware comfort with a kitsch aesthetic and a raucous, sometimes bawdy, sense of humour; and shelves and shelves of memorabilia relating to Briggs's own work.

Tidily gathered: Briggs's studio collection of pencils Leigh Simpson

But any sense of chaos is surface deep, because at second look a collector's sense of order emerges. Found objects—whether iron mattock heads or indigo-blue plastic cream-cheese containers—are arranged into carefully ranked installations. (The mattocks placed in a line, with an eye to their height and width, feel freighted with reminders of one of Henry Moore's studios in Hertfordshire where found objects are mixed with small maquettes.) At Weston, Briggs arranged ranks of china figures depicting the Snowman and Father Christmas on a stack of four shelves. In his studio, pencils, pens, erasers, artist's knives, are tidily gathered and arranged; drawers carefully labelled in his elegant hand. It is the house of an artist, but also of a careful researcher.

A sense of architectural order: a series of iron mattock heads arrayed above a doorway at Raymond Briggs's Sussex house. And a double page spread from Briggs's Father Christmas (1973) as the title character arrives at Buckingham Palace, in London. The original artwork wil be shown in the Briggs exhibition at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft Mattocks: Leigh Simpson. Father Christmas: © Raymond Briggs

It feels like the home of someone who might have been an architect in another life. This is apparent in the illustrations of houses in his books: whether it is his childhood home in Wimbledon, south London, Buckingham Palace or the Houses of Parliament. It is also evident in the space itself: on one wall of the studio, for example, hang the tools of an architect of his generation, including a set square.

Briggs was first and foremost a craftsman—though one with a formidable training at art school—a maker of things. And the patent dedication to his craft, apparent everywhere in the house, feels monkish indeed. Everything is arranged and labelled as in some late medieval scriptorum, but visual humour and jokes, and an anarchic self-deprecating vein of humour lie in wait around every corner.

The love of family

Affectionate biography: Raymond Briggs's portraits of his parents Ethel and Ernest Briggs, at Weston Leigh Simpson

Briggs was an artist and writer who drew heavily in his work, for narrative and imagery, on his happy childhood and his affection for his parents: Ethel Bowyer, a lady’s maid turned housewife, and Ernest Briggs, a milkman. He immortalised them in Ethel & Ernest (1986), an affectionate graphic biography. One of the most striking pieces at Weston—it will feature in the upcoming exhibition at Ditchling—is a pair of strongly outlined paintings of Ethel and Ernest on the doors of a downstairs cupboard, its surrounds in a strong red; each figure holding the artist’s gaze, with an unflinching honesty and genuine, unsentimental, emotion. It is a piece that, at one go, links Briggs back to the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and to the Omega workshop of the Bloomsbury circle. It is also a reminder of his schooling at Wimbledon School of Art, London's Central School of Art and Slade School of Art; his Slade contemporaries included the late Paula Rego and Victor Willing.

The art student: Raymond Briggs, self-portrait (around 1957), pinned against the wall by the frame of a second self-portrait Leigh Simpson

Another reminder of that schooling is a pair of self-portraits, seemingly done during his time at the Slade. They carry echoes of the studio drawings of students at that school dating back to the days of the formidable Henry Tonks in the early years of the 20th century, displaying a technique that is based on the Old Master tradition of drawing. In both portraits Briggs has the up-brushed "rocker" haircut of a young Lucian Freud, half a generation his senior. It was perhaps the sartorial uniform of art students of his generation.

The self-portraits are a reminder that one of the exhibits at Ditchling will be of the original artwork for the double-page spread in Ethel and Ernest when the parents come to discuss what they see as Raymond's outlandish decision to give up grammar school, with the promise of a university degree and steady employment, in order to go to art school—and their dismayed reaction: "There's no money in it. He'll never earn a living at it." "That lot's all long hair, drink and nude women."

A huge volume of memorabilia: Snowman cups and plates on the kitchen draining board at Weston Leigh Simpson

Underlying emotion

In the kitchen at the back of the house, Steph Fuller, director of the Ditchling museum, points out Snowman mugs, turned up on the draining board. “It is as if he has just left the room,” she tells The Art Newspaper.

Perhaps part of what makes Briggs seem still to be so vividly present, and one of the most touching things about seeing the house, is the extent to which he lived with the huge volume of memorabilia that his best-sellers generated. There are Snowman lavatory rolls, a Snowman towel in a bathroom, and on one of the sun loungers on the first floor. There are shelves and window sills lined with Father Christmas and the Snowman, and book advertising cutouts of some of his characters—Fungus the Bogeyman, the Snowman, the Boy.

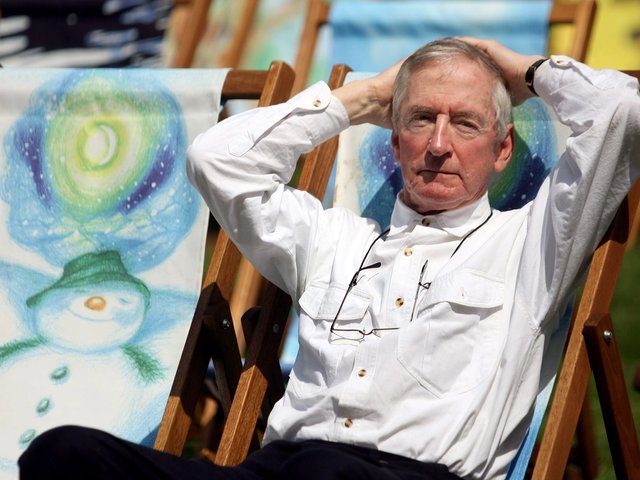

Anarchic humour: three photographs of Raymond Briggs besides one of the numerous pieces of Snowman merchandise in Briggs's Sussex house Leigh Simpson

In one happy juxtaposition, a publicity cutout of Ethel and Ernest has been propped up against the wall below a poster reproduction of Johannes Vermeer’s The Milkmaid (c 1660), hung oh so slightly crookedly at the centre of an otherwise blank wall. The connection is the deep underlying emotion in both works; an enduring stoicism, devoid of sentimentality, as apparent to a reader of Ethel and Ernest, as it is to an art lover lucky enough to see the Dutch master's jewel-like painting at the Rijksmuseum.

United in genuine emotion: at one end of Briggs's studio, a poster of Johannes Vermeer's Milkmaid hangs above a publicity cutout for Ethel and Ernest, Briggs's affectionate graphic biography of his parents Louis Jebb

It is that connection to a most un-English vein of emotion that makes Briggs's finest work—whether it be The Snowman or his anti-war masterpiece Where the Wind Blows (1982)—so powerful and universal in its appeal. He once recalled weeping through the audio recording sessions for the 2016 animated film of Ethel & Ernest. Listening to the actors playing the lead roles, Jim Broadbent and Brenda Blethyn, had made him feel that his parents had come back to life. Watching the finished film, he said, he had cried several handkerchiefs worth of tears.

Making a final visit to the studio and library of Raymond Briggs, and witnessing the total sincerity with which he wrote, drew, and joked, was to witness the deep wells of thought, wit and visual acuity that he was able to draw on when creating some of the greatest, and most unforgettable, graphic narratives of his generation.