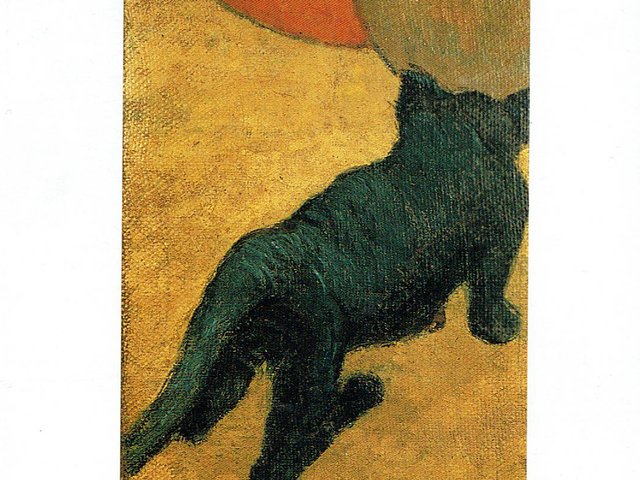

Paul Gauguin’s The Little Cat, which has been hidden away in a private collection for more than a century, has just gone on show at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum. This delightful work was painted while the French artist was staying with Van Gogh in the Yellow House in Arles.

Paul Gauguin’s Tropical Conversation (July-October 1887)

Credit: private collection via Wikimedia Commons

Artistically, this cat (or kitten) faithfully followed Gauguin on his far-flung travels. It first appears on the West Indian island of Martinique, where the feline is depicted in the foreground of Tropical Conversation. The cat is apparently lapping up milk and in its haste has put its front paws into the large dish.

A year later the creature appears again, in Arles, in The Little Cat. Since Gauguin did not take the Tropical Conversation painting to Arles, he may well have had a pencil sketch from Martinique at hand (such a drawing, from his West Indies sketchbook, still survives in a private collection). Or he could have simply remembered the animal’s distinctive pose.

What is most striking is that the cat reappears a decade later in Gauguin’s greatest masterpiece, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (detail below), done in 1897-98 on the island of Tahiti. This is a highly ambitious composition, nearly four metres wide.

A pair of cats appear prominently in the central foreground: one facing the viewer and the other in the Martinique pose, front paws in the dish. This time the black cat has become white, although with dark patches on its rear.

Paul Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (detail) (1897-98)

Credit: Museum of Fine Arts (Tompkins Collection), Boston

Looking at the newly unveiled painting of The Little Cat, what might appear to be simply a charming depiction of a feline is actually all that is left of what was probably originally a much larger still life. Gauguin was presumably unhappy with the full composition and at some point he cut away and discarded three quarters of the canvas, saving just the left-hand quarter (72 x 25 cm).

The clue about the original picture comes in a comment which Vincent wrote to his brother Theo on 21 November 1888. Gauguin was working on “a big still life of an orange pumpkin and some apples and white linen on a yellow background and foreground”.

Intriguingly, Van Gogh himself had earlier painted a still life with the slightly unusual combination of pumpkins and apples (September 1885, now Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo), so he may have suggested the composition to his friend.

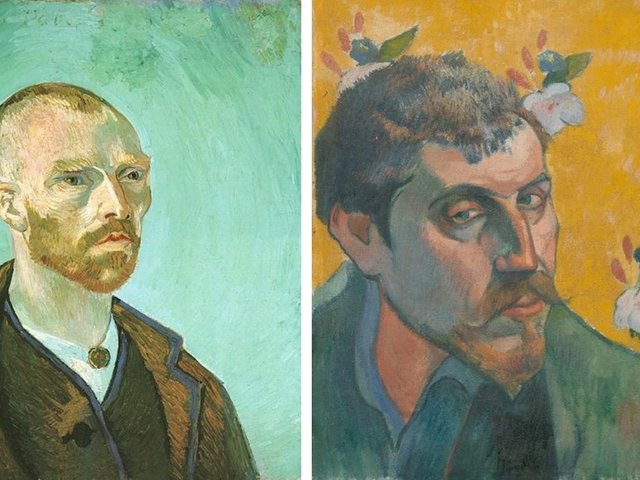

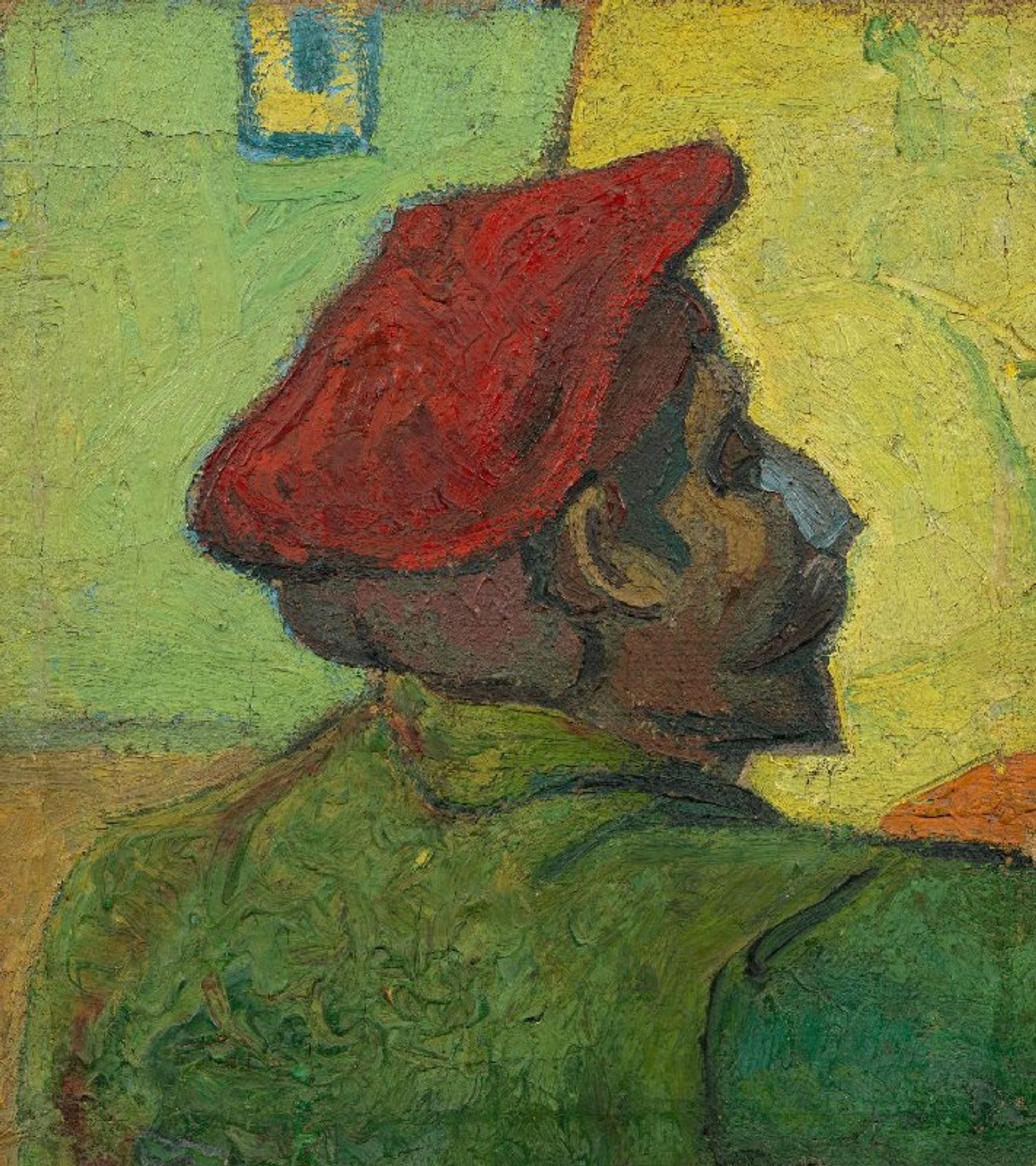

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Paul Gauguin (November-December 1888)

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

There is, however, a vague visual representation of part of Gauguin’s lost still life in the background of Van Gogh’s Portrait of Paul Gauguin. This too is a fascinating picture, since it had been largely dismissed as a fake since the 1930s and was not displayed at the Van Gogh Museum (it was recorded as “anonymous” in the museum’s 1987 catalogue). I suspected it might well be an authentic, although it is unsuccessful as an artwork.

Years ago I examined Portrait of Paul Gauguin in the conservation studio of the Van Gogh Museum and soon afterwards published an article in Apollo (July 1996), arguing for for its authenticity. Five years later it was accepted by the museum. For me, the mark of its acceptance was when the museum began selling postcards of the portrait.

Portrait of Paul Gauguin depicts the artist in his beret, working on a yellow canvas at a slight angle on an easel. In front of his face is the vague outline of a circular object and beneath this is a small area of orange, presumably a pumpkin. The portrait therefore depicts Gauguin in the act of painting his lost still life. In a sense, it mirrors Gauguin’s portrait of his friend with Sunflowers (August 1888) on his easel, probably done at the same time.

Paul Gauguin’s Vincent van Gogh painting Sunflowers (December 1888)

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The yellow background in both The Little Cat and the still life on the easel in Portrait of Paul Gauguin could well represent a tribute to Van Gogh—and his favourite colour. Just three months earlier Van Gogh had painted his Sunflowers with a bold yellow background, a picture greatly admired by Gauguin.

Research has revealed that The Little Cat and the Portrait of Paul Gauguin were both painted on jute, rather than traditional artists’ canvas. Although further investigations are now underway at the Van Gogh Museum, it is likely that the two paintings were made from the same 20-metre roll of jute which Gauguin had purchased in Arles soon after his arrival.

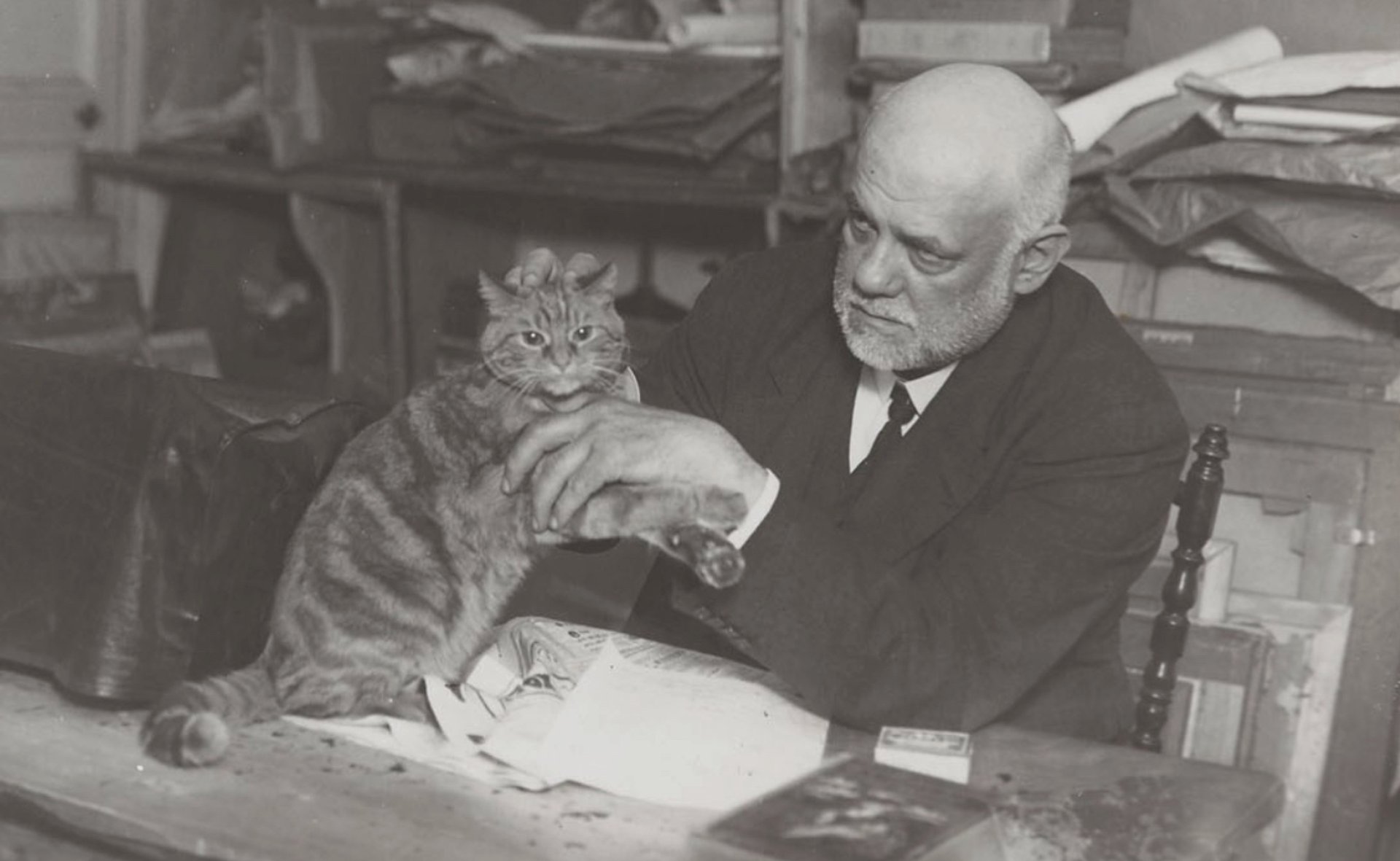

And what happened to The Little Cat? It was sold by Gauguin’s Paris dealer, the avant-garde figure Ambroise Vollard. He was renowned for his love of cats and one wonders whether Gauguin might just have included the two creatures in Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? partly to please his dealer.

Photograph of Ambroise Vollard in his Paris gallery (around 1934) (detail)

Credit: Thérèse Bonney © Regents of the University of California, Bancroft Library, Berkeley (Creative Commons)

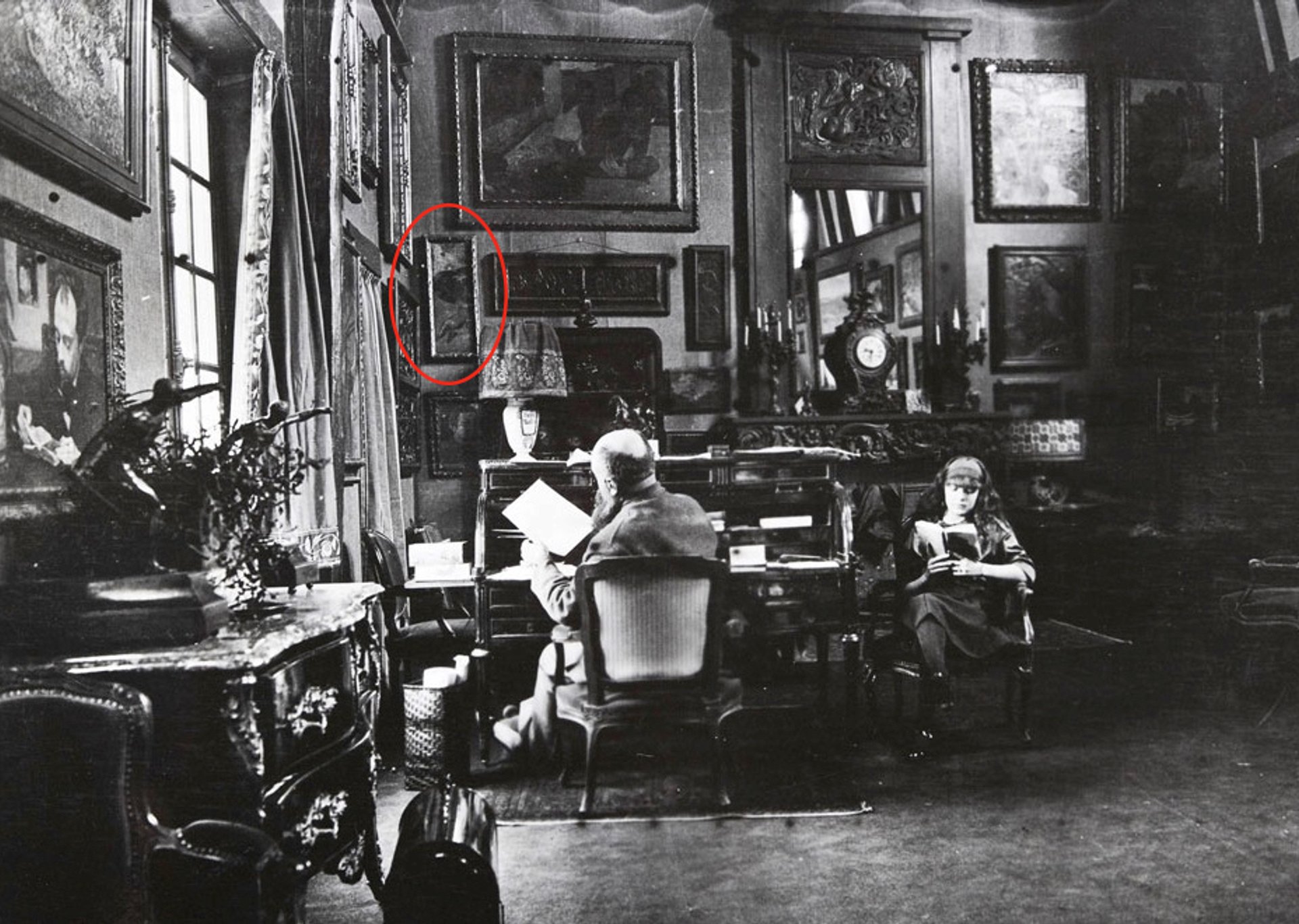

In 1906, three years after Gauguin’s death, The Little Cat was acquired by the French collector and artist Gustave Fayet. A 1913 photograph shows it hanging in his study.

Photograph of Gustave Fayet and his daughter Yseult in the study in the Château d’Igny, with The Little Cat hanging above the desk (1913)

Credit: © Musée d'Art Gustave Fayet à Fontfroide (MAGFF) - www.gustavefayet.fr

Fayet died in 1925. Although the present owner is not being named, it is presumed to be a descendant of the collector. It is most unusual that a painting by Gauguin has remained in the same family since its original purchase.

Looking at Gauguin’s playful cat, one can see the possible influence of Japanese prints in his mind, since these creatures frequently appeared in such works. Gauguin has not copied a cat from a specific Japanese print, but he may well have been inspired by them.

The Little Cat also shares another another similarity with Japanese prints: abrupt cropping. Gauguin cut the canvas by just lopping off the tip of the cat's tail. Such dramatic cropping was unusual in European art at the time, but common in Japanese prints. The fact that Gauguin’s composition is very prominently signed suggests that he was pleased with the cut-down fragment.

Now that The Little Cat is on loan to the Van Gogh Museum, further research will be done on the picture. Hopefully it will be possible to examine the edges of the canvas and to use non-invasive techniques to examine beneath the surface of the still life that is apparently on the easel in the painting.

In the meantime The Little Cat is being displayed alongside other paintings done by the two artists during their fateful ten weeks in the Yellow House, a period brought to an abrupt end when Vincent mutilated his ear.