You can think of the recent history of art museums as a series of expansions that opened museum doors ever wider. Since the 1970s, success came to be measured by growing audiences. Museums created programmes and spaces for youth and improved access for people with disabilities. During Covid-19, they became more community conscious, seeking to serve populations that had previously felt unwelcome. Yet one large and growing audience segment has generally been overlooked: older people.

The reason, simply, is ageism, an entrenched way of thinking and a form of discrimination to which we are only now waking up as a society. “Ageism is everywhere,” the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared, “yet it is the most socially ‘normalised’ of any prejudice and is not widely challenged, like racism or sexism.” Ageism is about stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel) and discrimination (how we act) toward others or ourselves, based on age.

Some might counter that museums are full of older people. This is true. A good number of older people do reliably show up. But if we are honest, that is not because museums are striving to attract them with purposefully designed programmes. No one knows how many would come if we really tried.

At this point, it might be helpful to offer a few definitions: Aging is growth—we age from the moment we are born. Senescence is the biological process of aging—the irreversible process of deterioration of body cells. The two are often conflated. When we first started asking museum directors about how their institutions were working to meet the needs of the older constituency, many admitted that they have not given the matter much thought. Some pointed to programmes for the visually or cognitively impaired. That response is itself ageist.

Why have museums not been more attentive to older people? Perhaps we feel anxious that the younger generation will not develop a lifelong habit of visiting museums. Or maybe it’s because the art museum is a mirror of social norms, which tend to favour the young, especially in the youth-obsessed United States. Whatever the case, we can likely agree: museums have not developed programmes and facilities for older people with the same zeal as they have for younger ones.

Museums have good intentions, but ageism festers in unexamined corners, from tiny print on wall labels, heavy entrance doors and lack of comfortable gallery seating to the assumption that older people are stumped by technology. Numbers tell the story: three quarters of the roughly $2bn spent on education initiatives annually by US museums goes to programmes for those under 18. The remainder is for the three quarters of the US population over 18.

Participants in a pottery workshop organised by StoryCorps Courtesy StoryCorps

We were only made fully aware of this issue when we started working with E.A. Michelson Philanthropy, a Minneapolis-based foundation that promotes creative aging programmes for older museumgoers. The foundation has been supporting what are called “vitality arts” courses for older adults led by professional teaching artists. The classes forge skills, friendships and purpose—and are exceptionally popular. We helped assemble a nationwide network of art museums to offer such classes, challenge education departments to broaden their reach and address ageist practices and policies museum-wide. Close to 50 museums across the US now have some experience with this line of work.

That is a start. But it hardly measures up against the scale of the demographic transition we face. By 2035, there will be more adults over 65 than children under 18 in the US. People are living much longer. A child born in the US today will have a 50% chance of living to 100.

For museums seeking to navigate this new landscape, there are thorny issues to reconcile. Firstly, shifts in age intersect with changes in the racial composition of the population. Older cohorts are less diverse than younger ones. Currently, 20% of the population is over 55, and 75% of them are white. The majority of Americans under 18, by contrast, are people of colour, and by 2045 most of the population will no longer be white—except for those over 55. The contrasting racial mix of younger and older age cohorts complicates policy-setting around aging in a museum field that has been focusing, for good reason, on diversity and inclusion.

Meanwhile, it will not be lost on those seeking to make museums sustainable that older cohorts command vast assets. About 70% of America’s wealth is held by those 55 and older, who, were they a country to themselves, would have the world’s third largest economy. This wealth will swell to $28 trillion by 2050.

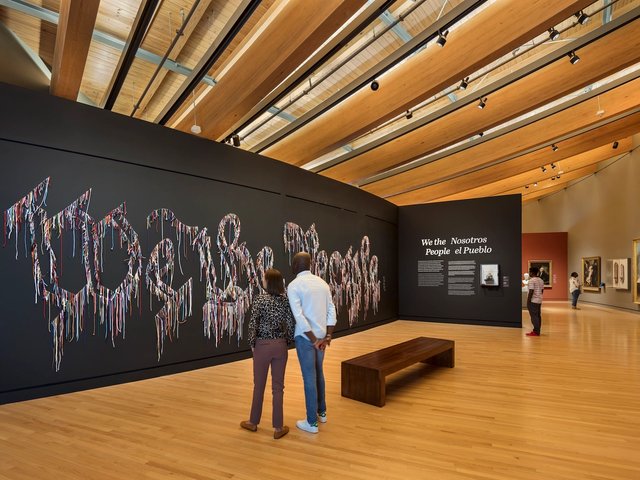

MParticipants in a graffiti-making workshop at the Minneapolis Institute of Art Courtesy the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Older people are healthier and more educated than in prior generations; they have time and a thirst to learn. Nonetheless, in the US only 21% of them visited a museum last year. The message should be clear: there is vast potential here for the development of museum audiences and for museum funding. We call this the “longevity dividend”.To tap into it, museums will have to test long-held assumptions.

Steps to success

How can we tell that a museum is respecting and valuing older audiences? We have come up with a dozen priorities that form a road map to an age-friendly museum:

- Look internally at ageist attitudes and practices, recognising that aging is not the same as senescence—that aging is growth and senescence is growing old.

- As has happened in regard to gender, race and formerly excluded voices, review collections, acquisitions policies, exhibitions and programming through the lens of aging.

- Continue to offer programmes for older adults living with cognitive decline, and also provide creative-aging programmes for the more than 80% who are not cognitively challenged.

- Present an image of an age-friendly institution in press, social media, advertisements and annual reports to show that the museum is addressing ageist blind spots.

- Recognise that replacing older volunteer docents with younger paid educators can be perceived as ageist—and that perceptions matter.

- Ensure that the museum’s board and staff are representative of all ages.

- Include ageism in the institution’s Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion (DEAI) statement (most institutions do not).

- Do not measure success only by the number of younger visitors—has a museum ever issued a press release touting the rising number of older visitors?

- Adopt human-centred design standards suitable to people of all ages (guidelines are widely available).

- Raise designated endowment funds for supporting activities for older people, just as many museums have such funds earmarked for serving younger ones.

- Open a facility specifically tailored to the needs of older visitors.

- Partner with organisations outside the museum field to develop an age-friendly community, to reach older people at scale.

Museums are lagging rapid developments in public policy, healthcare and the commercial sector, where older populations are now firmly on the agenda.

Outside the museum field, awareness about aging is on the rise. The WHO launched its Decade of Healthy Aging initiative in 2021, running through 2030. The Age-Friendly Cities and Communities network counts nearly 1,500 members already in 51 countries, covering over 300 million people, each working to become friendlier to older adults. Museums should refresh their own practices and act as civic leaders in advancing their communities as age-friendly cities.

The opportunity to evolve the art museum is hiding in plain sight. Older people are legions of potential visitors. They can be part of the museum workforce. They are museums’ once and future donors. And they are yearning to feel engaged and valued. The time for museums to act is now.

- Brian P. Kennedy is the former director of the National Gallery of Australia, Hood Museum of Art, Toledo Museum of Art and Peabody Essex Museum

- András Szántó is an author and cultural strategy advisor based in New York; his most recent book is Imagining the Future Museum: 21 Conversations with Architects

- This article was edited from a keynote presentation for the Vitality Arts Project for Art Museums 2023 Gathering in Minneapolis (1-3 November 2023)