London’s British Museum is a child of the Enlightenment. Sculptures in its Grecian pediment announce it as the temple of Lord Elgin’s Parthenon marbles, arguably its greatest treasures, which it acquired in 1816. But before Elgin, there was an earlier British Museum and another sculpture hall, purpose-built at the beginning of the 19th century for a group of classical sculptures that were originally far more famous. These were the Townley marbles which, with over 8,000 smaller antiquities, belonged to the remarkable maverick 18th-century connoisseur Charles Townley. It has taken the sensational theft of many hundred items from the museum—revealed last August, when The Art Newspaper reported that “many are likely to be engraved gems and glass from the Townley [collection]”—to retrieve his name from the obscurity into which it had dropped.

Townley the Europhile bachelor

Townley lived in the glory days of the Enlightenment, and the fate of his extraordinary collection shows us how this era—now tainted by association with wealth built on the enslavement of other nations—is being recast for posterity. Born in 1737 into an established gentry family of Catholics in Lancashire, Townley was a Europhile bachelor with country estates and a London townhouse. Excluded by his religious faith from parliamentary office and parts of society, he dedicated his life to the connoisseurship of antique sculpture, buying the best things he could find in Italy and appointing agents to continue this traffic on his return. A copious correspondent and note-keeper with a wide acquaintance, this witty, mordant, obsessional and fascinating man—who has yet to be the subject of a biography—comes alive in hundreds of pages of letters and manuscripts acquired at auction by the museum in 1995, after being sold by one of Townley’s heirs a decade earlier.

Antique sculpture was then the hottest commodity on the art market, prized for its romantic associations, rarity, marmoreal beauty, novelty and value. But Townley was omnivorous, amassing a vast library, hundreds of prints and small antiquities, Egyptian, Persian and “Hindoo” pieces, terracottas and bronzes as well as carved gems, glass intaglios, cameos and seals, some the gifts of fellow collectors, others douceur sent by Thomas Jenkins and Gavin Hamilton, his agents in Italy. All gave context to his core collection, for he constantly rearranged and regrouped his antiquities according to his preferred theory of a (covertly pagan) classation mythologique. Having no legitimate children, Townley made his collection his monument for posterity. His ambition was eventually to show everything together in one fantastic pantheon that would illustrate the conjoined taxonomies of the ancient world mythologies.

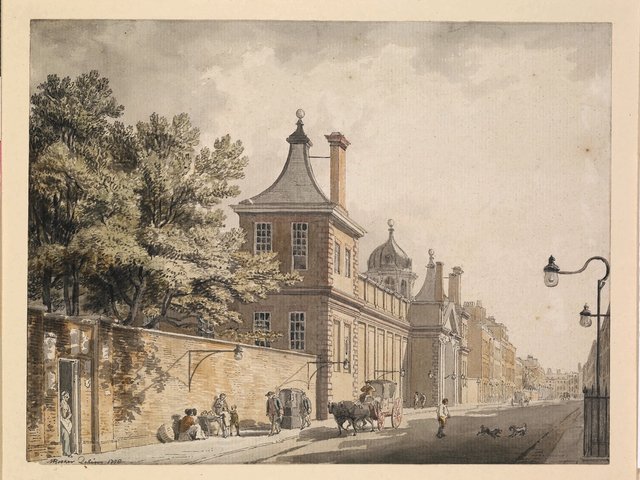

Within a decade, his collection was one of London’s main attractions, filling the deficiency in the British Museum’s holdings. He showed it by appointment in his house-museum in Park Street (now Queen Anne’s Gate), overlooking St James’s Park.

Johann Zoffany painted him there in 1782 among his “august family” of sculptures. By the 1790s he had been permitted to join the elite club of the Society of Dilettanti with fellow collectors such as William Hamilton and Lord Bessborough, and been appointed a trustee of the British Museum. Soon after, he commissioned a pair of paintings that show us how his public-private museum functioned then, with a plethora of altars, busts, sarcophagus and frieze panels cramming the walls of his dining room and entrance hall, and fashionable ladies sketching or poring over the catalogue he was constantly revising.

Townley made his collection his monument for posterity. His ambition was eventually to show everything together in one fantastic pantheon that would illustrate the conjoined taxonomies of the ancient world mythologies

Anticipating that Townley would give them his collection, the museum’s other trustees gained his approval to build a classical rotunda and gallery extension to receive it, annexed to the old museum building at Montagu House, in Bloomsbury. But it did not satisfy him: just 12 days before his death in 1805, Townley added a codicil to his will, desiring that his heirs instead build his favoured pantheon to hold them at his country estate of Towneley Hall, ultimately forcing the museum to purchase them for £20,000 in 1805. (The museum acquired Townley’s smaller antiquities from his cousin and heir Peregrine Townley in 1814.)

From 1808 the Townley marbles held sway in their new gallery at the British Museum. Then, a decade later, and after much prevarication, they were joined by the Parthenon Marbles (then called the Elgin Marbles), which were relegated to a gallery added to the side of Townley’s. At first the old guard of connoisseurs were scathing about these crude and dirty pieces of “architectural” sculpture, but as the Parthenon Marbles came to be recognised as lodestones of genuine Greek culture, Townley’s were inevitably reclassified as lesser, Roman copies of Greek originals. The new mood was for displays illustrating the “chain of art”, a progression of world civilisations culminating in the Greek ideal, with Elgin’s at the apex, and Townley’s “decadent” art charting the “slow decline” that followed. (The museum was rebuilt in stages between 1823 and 1852 to form its present Grecian palace plan.)

In the 20th century, Townley’s marbles gradually slipped out of view. Elgin’s sculptures now reigned supreme in the gallery donated by the art dealer Joseph Duveen, Townley’s lost their hegemony as individual archaeological specimens, separated and dispersed throughout the museum. After the Second World War, they were moved en masse to the museum’s basement, while elsewhere in the museum’s stores, the remainder of Townley’s antiquities waited in boxes and on shelves. In the 1970s the then curator of Greek and Roman antiquities, Brian Cook, started on a thoughtful programme of research on Townley, taken up in a much broader context by his successor, the scholar Ian Jenkins. Publishing Archaeologists and Aesthetes in the Sculpture Galleries of the British Museum 1800-1939 in 1992, his seminal history of the museum’s foundations, Jenkins wrote that “the museum had forgotten its own history”.

Out of sight

Jenkins died in 2020, long before his time. Townley’s marbles remain below ground in characterless basement rooms that are open only occasionally. His Discobolus and a few more works grace the upper galleries, the secret of their fascinating provenance revealed only by the acquisition number on their museum labels.

In succeeding years, and with Jenkins gone, it now appears that Townley’s collection was raided with total impunity for hundreds of small valuables to sell on eBay. A good proportion of the gems, pastes and intaglios (some antique, some fakes or copies commissioned for Townley’s delectation from the workshops of skilled fabricators in Rome) were never individually photographed or inventoried and so it is doubtful that most can ever be traced. Ittai Gradel, the Danish art dealer and expert who first raised the alarm about the thefts, could only confirm his suspicions about the hundreds of precious objects offered for sale in 2021 on identifying just three exceptional pieces in the museum’s catalogue.

Lately the museum has begun to interrogate its own past once more, but with a new agenda focusing on de-mythifying and reinterpreting its collections. In 2020, the museum’s then director Hartwig Fischer told The Guardian that the museum had “accelerated and enlarged its work on its own history, the history of empire, the history of colonialism and also of slavery. These are subjects which need to be addressed, and to be addressed properly. We need to understand our own history.”