The established Los Angeles-based artist Henry Taylor is having something of a renaissance. Taylor was thrust into the limelight in 2017 when his painting of Jay-Z appeared on the cover of New York Times’s style magazine T. A major show of his works is currently running at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York (B Side, until 28 January 2024). Crucially he took centre stage in Paris earlier this year when a show of 30 new paintings, sculptures and works on paper opened at Hauser & Wirth (From Sugar to Shit, until 7 January 2024), inaugurating the gallery’s new space in the French capital. “Combining figurative, landscape and history painting, alongside drawing, installation and sculpture, Taylor’s vast body of highly personal work is rooted in the people and communities closest to him,” the gallery says in a statement. This interview was initially published by our sister newspaper, The Art Newspaper France.

The Art Newspaper: In June and July, you relocated to a studio in Paris’s Bastille district. Where did you visit and what did you see?

Henry Taylor: Bastille was nice, you know? The location of the apartment and studio was great. There were restaurants down below… a nice little courtyard. Friendly cats. Pigeons on my windowsill. It was cool. I was taking French [lessons] twice a week. I already had friends and knew people there.

I went to [see] The Who and to the Kendrick Lamar concert. Kendrick came to my studio several months ago—that was the first time I met him. I worked a lot, I felt compelled to. There were so many blank canvases in the studio. I always make works when I travel, not necessarily for an exhibition but because I want to. This time, I really concentrated.

Among the museums you visited in Paris, which ones had the greatest impact on you?

I went to the Picasso Museum. I went to see the Basquiat-Warhol show at Louis Vuitton Foundation. I saw the Manet-Degas exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay. And I always want to go back and look at Bonnard and Vuillard, going right to those guys.

I like going back to the d’Orsay. One thing is the museums don’t change. It’s like going back to your grandma’s house. In seventh grade, I had an English teacher, Teresa Escareno, who was very important to me. I also have a self-portrait of her, which her daughter gave me. So, at the d’Orsay, I think about her. I met her when I was in sixth grade because her husband was a PE [sports] coach. She was my first introduction to painting—to Cézanne and Vuillard, impressionism and post-impressionism. When I started going to her house it was with the basketball team and we would be over on the side talking about painting. She was my first introduction to Bonnard.

What do you mean by the title of the exhibition, From Sugar to Shit?

I was trying to invoke my mother in the show, maybe not just in the form of a painting but in the form of words. That’s something she would say. Then I thought about a different title. And I came back to From Sugar To Shit. It’s the idea that situations change and that they get worse and worse. Some things are just sweet and then they go sour. That’s not being optimistic, I try to be a hopeful person but this is what I'm going through.

What did you paint in Paris?

There were so many blank canvases there, I had to assess the situation. If there were golf clubs there, I might have gone golfing. The canvas was there, and I think just the fact the materials were there, I felt compelled. I always make some work when I travel but not for a show. I might have made six or seven large paintings and some smaller ones. Some were of people I met in Paris. This girl from Gabon [or[ my friend Harif invited some people over one night and I painted them.

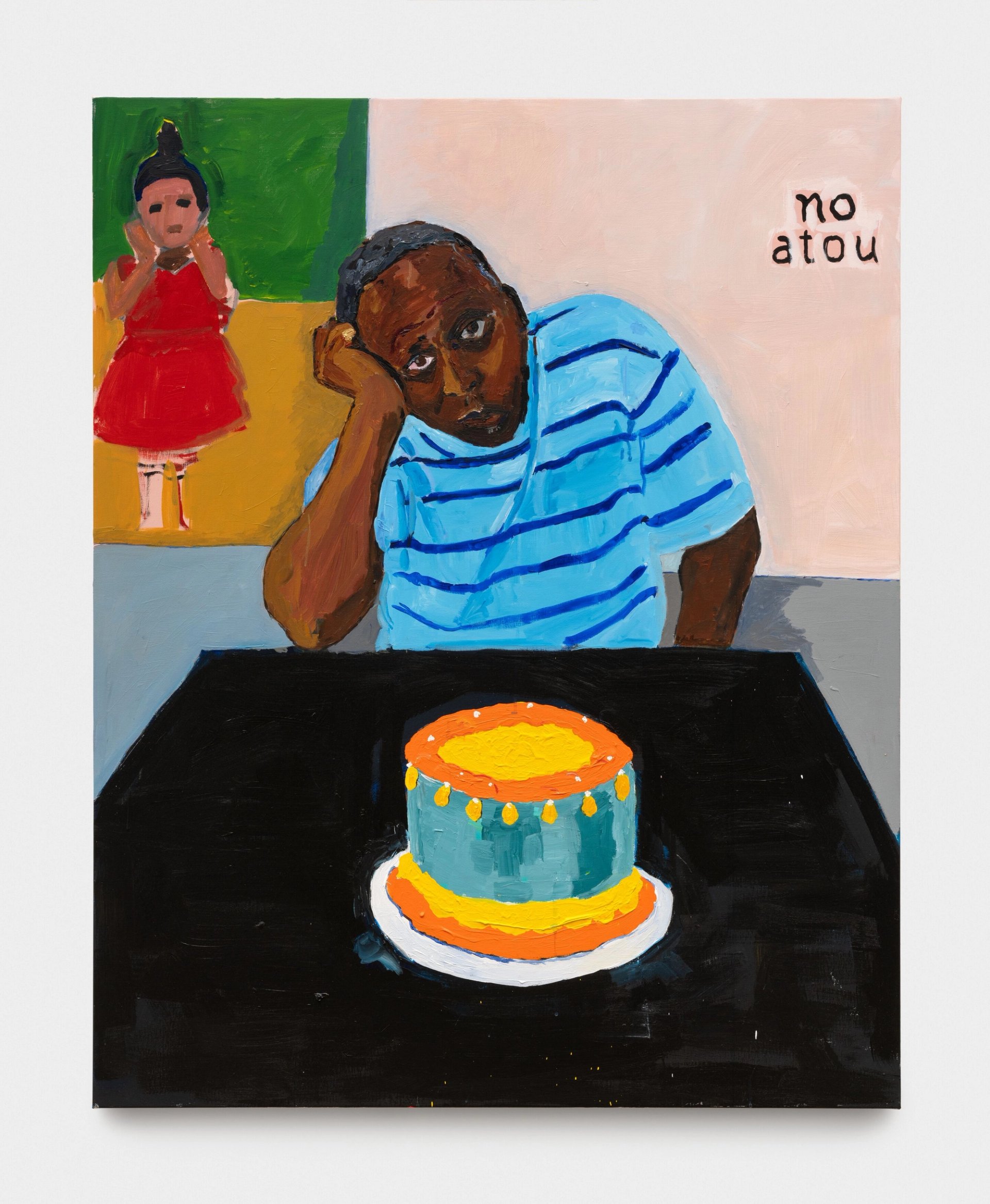

Henry Taylor, no atou (2023)

courtesy Hauser & Wirth

In the exhibition, there is also a self-portrait in which you wear a striped t-shirt reminiscent of Picasso.

My birthday was here in Paris. And my daughter sent me a cake, the most beautiful one I have ever received. So I thought of the painter Wayne Thiebaud and all the cakes he painted. And I said to myself that I couldn't cut it, that I was going to look at it. And then there is the painting of my daughter that I painted here in the background. So that is me on my birthday. Perhaps this pose also comes from paintings that I looked at in history but it is mostly an image of being alone. And these words behind on the wall are from [Paul] Gauguin, I think it’s Tahitian slang, which means: “I don’t care.”

After ten years working as a psychiatric technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital, what prompted you to change direction and enrol at Cal Arts (California Institute of the Arts) where you received your BA in 1995?

My mother always said: “Put your best foot forward.” My brothers were athletes. I never thought of art as a career. I was told I would never make money. I was a nurse for ten years. Painting was something I had put on a back burner. I had a teacher, James Jarvaise [at Oxnard Community College], who was actually French and he told me to apply to CalArts. And that’s what I did.

You often paint people who are close to you but also individuals you do not know. Does knowing your model make a big difference?

One of my brothers was a barber, so I think about heads in a barber shop and you want to do a nice cut! You might think about a different technique but sometimes you just get lost. You just paint the body. It’s just probably like the surgeon. It may be different with the strokes or with the sitter—you want to appease; you don’t want to freak them out.

Do you create your sculptures the way you paint, by bringing together people around you or by assembling objects that you come across?

Sometimes it is random, even in paintings. There is a form of spontaneity; I don’t really plan everything. I see someone, I ask them to sit for me and I grab my brushes. In the same way, I grab materials that resonate with me and later put them together. It takes time. Sometimes I need a helping hand. Sculpture is, for me, so new and fresh.

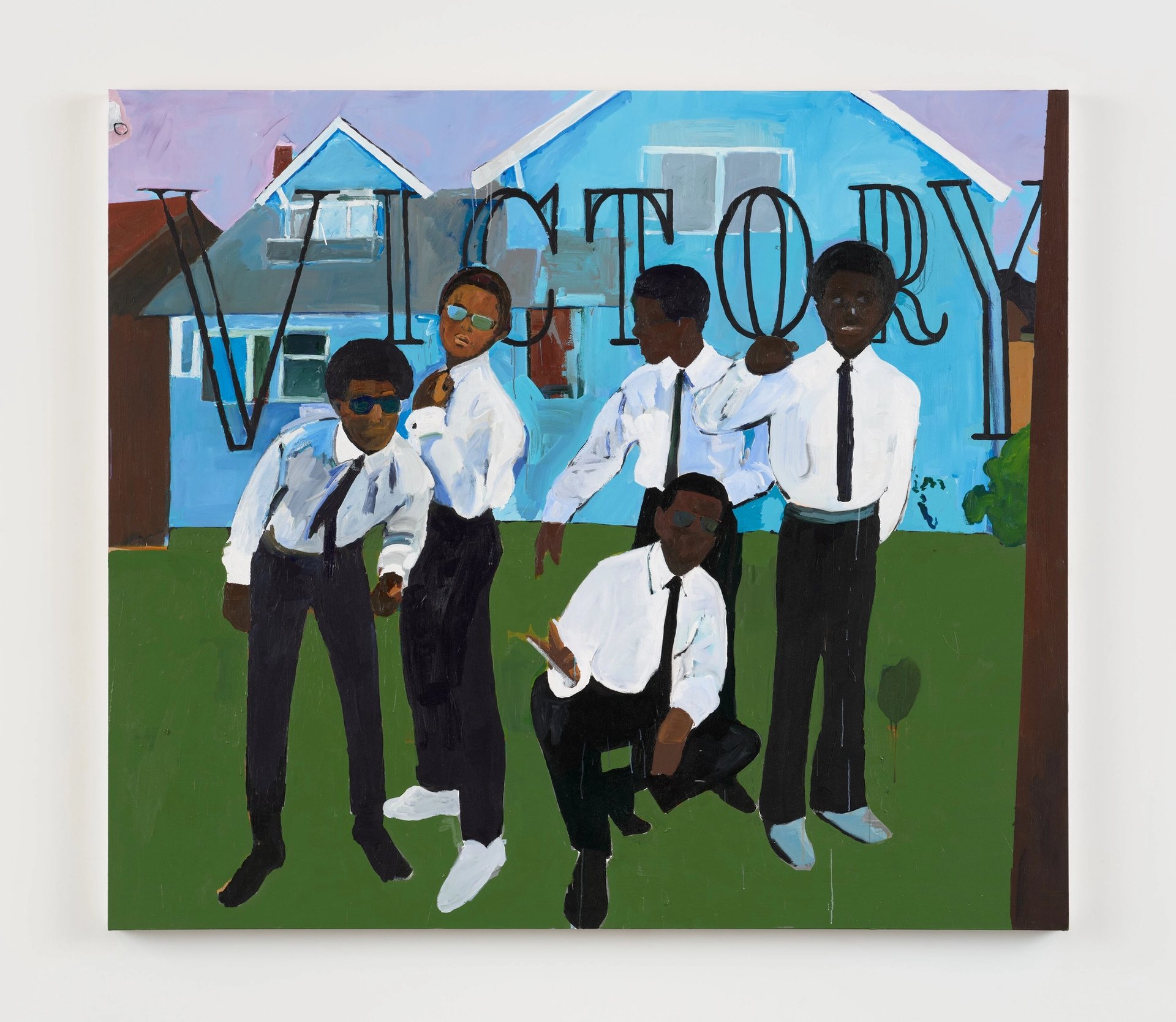

Henry Taylor, One Tree per Family (2023)

courtesy Hauser & Wirth

How do you come up with the idea of a sculpture such as One Tree per Family (2023), for example?

I was in my studio, I was thinking about my brother Randy, who was part of a movement that he introduced me to. I think about him and things I’ve learned from him. My brother went to Black Panther meetings [he was associated with the Ventura County chapter of the Black Panthers]. When we think of this movement, we think of iconic objects like the leather jacket that the members wore. The hair is a connection to the 1960s movement.

It’s my way of paying homage to my brother and all people. It’s me reacting and being somewhat nostalgic at the same time but also looking at what has been happening recently. Because then there’s also the Black Lives Matter movement. We’re not being aggressive; we are playing defence here. It doesn’t have to be literal, you know? There is a sense of pride too. My brother is someone I look up to, to this day. He is always passionate and sincere.

Do you always paint in your studio?

No. I went to Gorée [off the coast of Senegal], to Kehinde Wiley’s artist residency, Black Rock. I asked him if I could stay an extra week and I painted until 20 minutes before my ride came. I tried to paint everyone who worked there. For my exhibition in New York in 2019 [at Blum & Poe gallery], I must have made a dozen paintings: Zadie Smith, Rashid Johnson, Derrick Adams, my daughter... I would go to my openings with my paint in an egg carton. I was in Colombia and painted someone on the street. I would like to draw in museums but I get a little embarrassed. I paint everywhere.

Is travel important to you?

Yes, it's important. I'm currently trying to organise a trip to Burkina Faso but they say that they’re having some trouble at the moment so I might go to Egypt, where I've never been. I think it's time for me to go there. In my studio in Paris, I left two paintings [showing] pyramids. I was thinking of [Philip] Guston.

How do you know when to stop?

You just have to look for a while. Sometimes we don’t even know how beautiful things are. It’s like a Rothko and it’s really just a sunset over water: only two things, the horizon and the ocean. Why is it so beautiful and so minimal? Sometimes you’ve seen it every day, but you don’t really look at it.

If I look at an early Guston or [Willem] de Kooning and it’s all over the place, you see that people are starting to take away less. Sometimes [it’s] just the essentials—less is sometimes more.

Henry Taylor, I got brothers ALL OVA the world but they forget we're related (2023)

courtesy Hauser & Wirth