“War, what is it good for? Absolutely nothing!” The counterculture Motown classic seems particularly relevant as we lurch into a new year beset with appalling conflicts and atrocities. In the face of such relentless warmongering, it may seem perverse to be highlighting a museum devoted to conflict, but I’d argue that in these horrifically embattled times never has the role of London’s Imperial War Museum (IWM) been more important.

The First World War was still raging when in 1917 the British government approved a proposal to collect and display material that recorded the military and civilian war effort and the sacrifices made by the UK and its empire. Since then, the IWM has expanded its remit to all conflicts involving British or Commonwealth forces, and from its inception this has included amassing and commissioning a rich and unique collection of art in all media.

The IWM’s collections not only record modern warfare and its impact but also its consequences. And this can even include the way that human conflict changes the parameters of art itself. Surrounded by missiles, tanks and warplanes in the museum’s atrium lies the twisted form of a wrecked car salvaged from a suicide bomb attack in Baghdad in 2007. Laid out like a corpse, this grim relic of the Iraq War punctures the bombast of all this lethal weaponry and reminds us what it actually does. The mangled wreck was donated by the artist Jeremy Deller after he had toured it around America, accompanied by a US soldier who served in Iraq and an Iraqi citizen living in exile.

One of the most famous works of the IWM collection offers an earlier coruscating comment on the consequences of war. John Singer Sargent’s giant painting Gassed (1919) depicts a line of First World War soldiers with bandaged eyes after a gas attack picking their way across a devastated landscape, each man holding the shoulders of the soldier in front.

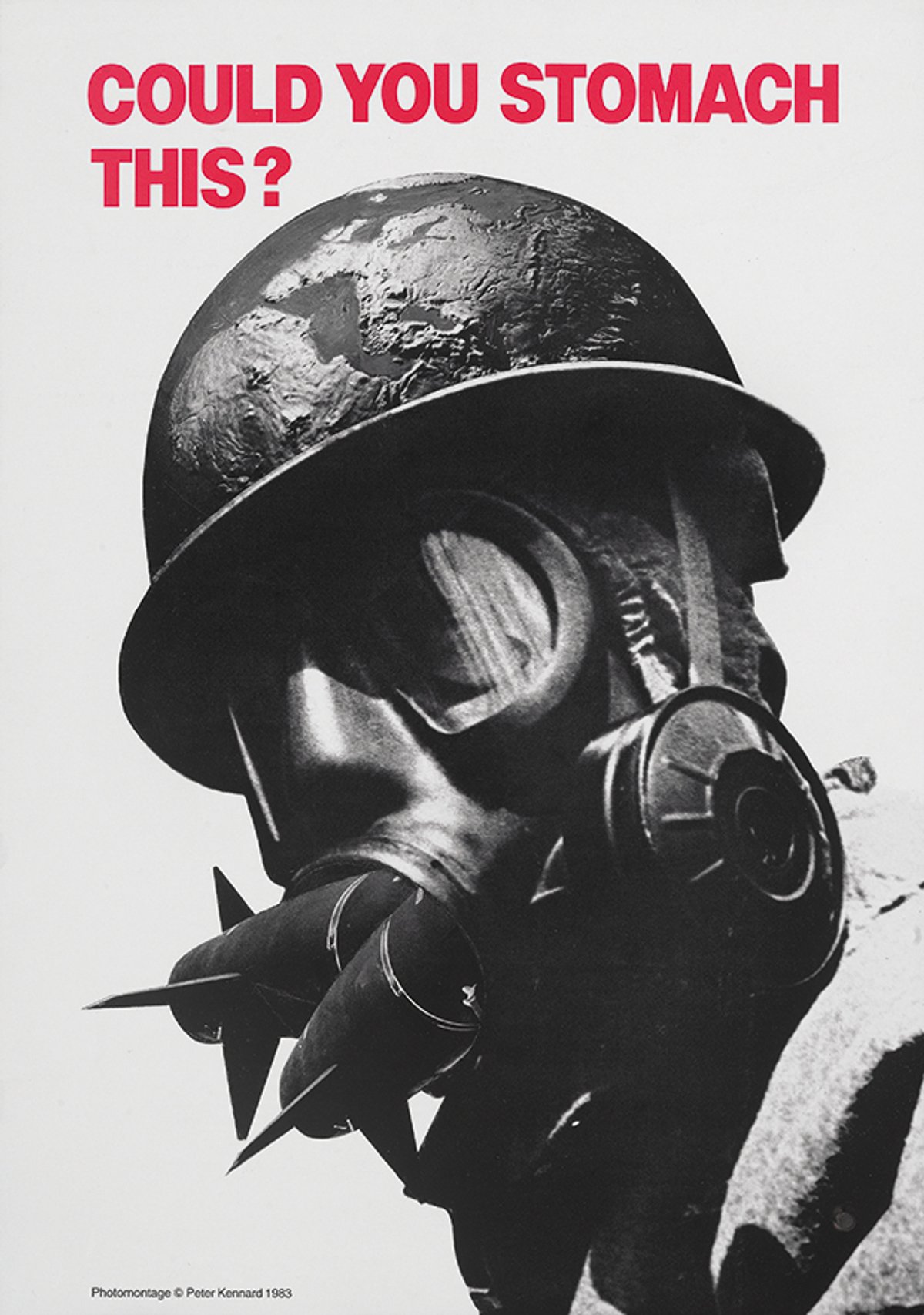

This 6m-long work forms the centrepiece of a new suite of permanent galleries at IWM designed to house its visual art holdings and to combine art, film and photography for the first time. The Blavatnik galleries opened in November to coincide with Remembrance Sunday, and have been organised thematically rather than chronologically. There are sections devoted to Mind and Body; Perspectives and Frontiers; and the Power of the Image, exploring themes of propaganda and protest. This radical re-presentation charts how artists have recorded, commented on and borne witness to the wars and conflicts that have shaped our world as well as underlining how art—for better and for worse—shapes how we think and feel about war itself.

Celebration of service?

Courageous curating enables powerful conversations to strike up between works made at very different times. Placed directly front of Gassed in the Mind and Body galleries, Steve McQueen’s Queen and Country (2007) is a memorial to the 160 British soldiers killed in Iraq in the form of sheets of postage stamps, each bearing a photograph of a deceased solder, along with their name, age, regiment and date of death. Presented in a special wooden display cabinet with drawers that visitors can pull out, it is up to us to decide whether Queen and Country is a celebration of military service or an indictment of loss of life—or both. The Royal Mail declined to issue his designs as official postage stamps, and McQueen regards the work as incomplete until it does.

The plethora of bodily depictions range from Henry Moore’s tender 1941 Shelter drawings of huddled Londoners sleeping in Underground Stations during the Blitz, to Mohammed Sami’s haunting 2022 painting Abu Ghraib in the Power of the Image gallery. The latter depicts the shape and shadow of a pair of trousers which also recalls the figure of Ali Shallal al-Qaisi, an Iraqi man detained and tortured at Abu Ghraib prison between 2003 and 2004. Images of brutalised bodies don’t get more powerful than in the paintings by Edith Birkin and Doris Zinkeisen of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp: Zinkeisen was the first artist to enter the camp shortly after liberation in 1945, while Birkin draws on her memories as a survivor of both Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz camps.

Changing forms of conflict are also charted, from the mass carnage of earlier wars to the more complex, fragmented but no less lethal conflicts of recent years. Renditions include Paul Nash’s apocalyptic painting of blasted First World War battlefields to Willie Doherty’s quietly charged 1995 photograph of a blocked road in Northern Ireland and Mahwish Chishty’s 2013 painted collages and photo-transfers that combine the shape of a Reaper Drone with the colours and patterns of Pakistani folk art.

In the light of recent events, viewing Rosalind Nashashibi’s Electric Gaza, filmed in the Gaza Strip in 2014 is almost unbearable. How many of these buildings are still standing? How many of the women pushing prams and children riding bicycles are now dead? For the sake of those currently being attacked everywhere, it is crucial that we look long and hard at all these images and think what each of us can do to make it all stop. Now. Let’s hope one day the IWM’s galleries will stand as a memorial to what was, and not be a savage reminder of how little we have learned.