Between 2020 to 2022, the population of Florida grew by 707,000, according to US Census data. At the same time, California and New York each shrank by more than half a million people—a number of them moving to Florida (and Miami specifically), attracted by the weather, comparatively “affordable” prices and lack of state income tax. But as Miami officially becomes the least affordable housing market in the country, local artists and organisations responsible for building the city’s vibrant art scene struggle to pay for their homes and workspaces.

Loni Johnson, a multi-disciplinary artist and educator born and raised in Miami, has seen the different waves of gentrification push people out of various neighbourhoods throughout the years. “Real-estate development and art in Miami go hand in hand; you cannot separate them,” she tells The Art Newspaper.

What happened in Wynwood in the 2000s is a prime example. First, artists and galleries gained a foothold in the neighbourhood in their search for affordable space. A group of local art dealers, artists and curators founded the Arts District in 2003, a year after Art Basel came to town for the first time. By 2005, developers were buying up property in the area, attracted by the culture of the neighbourhood, and subsequently raised rents. By 2015, Wynwood’s working-class and artist communities were priced out. And as artists and galleries moved to other neighbourhoods, such as Little Haiti or Allapattah, chasing affordable spaces, the value of real estate in these areas rose as well.

“Artists and art spaces have always had this relationship where they go to areas, bring hip energy and beautify neighbourhoods, then developers come in to buy properties and raise the rents,” says Cornelius Tulloch, a Miami-based artist and designer. Tulloch, who is involved with the Black Reconstruction Collective (a group of artists, architects and designers working towards the “incomplete project of emancipation for the African Diaspora”), emphasises the importance of policies protecting affordable housing. “We want to challenge this and find ways to make space for us to survive and stay here,” he says.

A dearth of affordable housing

A 2018 study found that Miami had lost an average of 1,286 affordable-housing units every year since 2013 due to rising prices, developer-friendly policies, and a lack of rent control. That same year, a team of housing and research specialists and Ned Murray, associate director of the Jorge M. Pérez Metropolitan Center at Florida International University, presented a comprehensive affordable-housing master plan. “The theme of the plan was to preserve the soul of the city, which was the neighbourhoods,” he says. Unfortunately, it was never adopted. “We thought this would interest the city and commissioners, but no,” he says.

The city has changed dramatically in the five years since Murray’s ill-fated proposal. “If it was already bad in 2018, it got even worse in 2022,” he says, referring to the pandemic-era population spike. “Some neighbourhoods now have New York City rent prices, increasing by 40% over the last two years, but Miami’s economy is based on leisure and hospitality jobs that tend to pay minimum wage.”

In a recent survey, Bakehouse Art Complex—one of the largest and oldest artist-serving organisations in Miami, providing affordable housing and studios since 1985—found that approximately 85% of its artists earn $50,000 per year or less, with more than 30% earning less than $20,000. Artists earning less than $50,000 reported spending almost 50% of their income on housing alone. Artists making less than $25,000 spend a whopping 73% on housing. Many of them are people of colour.

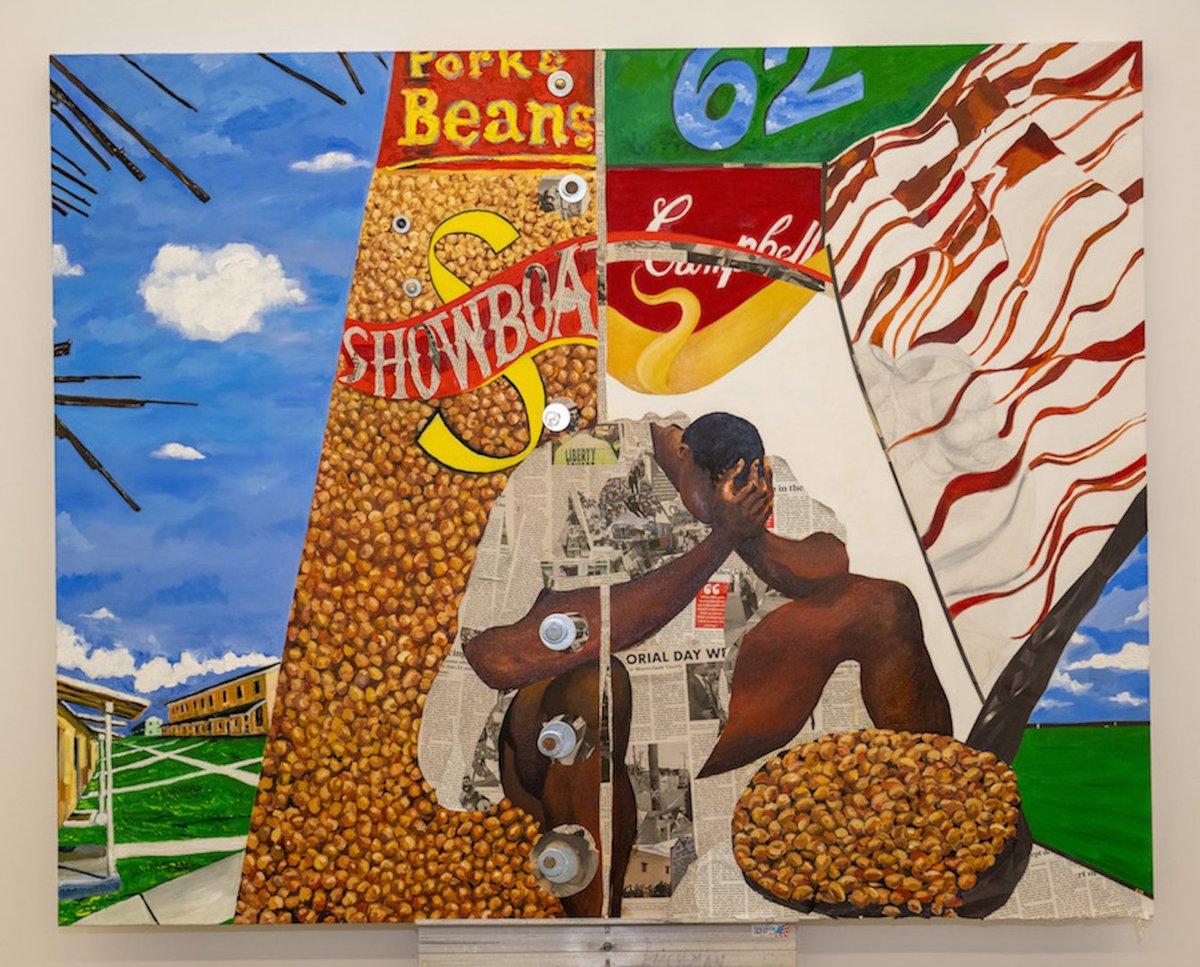

Cornelius Tulloch, installation view of Poetics of Place at Locust Projects (2023) Courtesy the artist

Art and displacement

Ever since Art Basel’s establishment in the area, Miami as a city has undoubtedly seen the monetary return on investing in art. Miami-Dade County now has one of the most successful public-art programmes in the country, with 1.5% of construction costs for government buildings allocated to new public art. Although this provides artists with jobs and opportunities, without state-mandated affordable housing to protect those who cannot afford rising rents, “that same infrastructure system works against the artists, because it can later cause displacement,” says Tulloch, who has seen many of his own artist friends leave for other, more affordable cities—like Atlanta. His most recent installation at Locust Projects, Poetics of Place (until 10 February 2024), centres on the “porch space” as a site for community and a tribute to the history of Black and Caribbean neighbourhoods at risk of erasure.

Public art can also change a neighbourhood's aesthetics, especially when commissioned to outside artists. While working on public murals in Wynwood, Sydney Maubert—an artist, architect and professor of Cuban and Haitian descent who uses painting as a “tool for architectural storytelling”—noticed how transplants “bring a different aesthetic vernacular” that is often more commercial. This new vernacular slowly displaces Miami's Indigenous, Black and Caribbean aesthetics, which Maubert aims to recover in her own work, some of which is part of the group exhibition DISplace at Green Space Miami (until 15 March 2024). The show, in which local artists grapple with displacement, revolves around a spoken-word piece by the artist Arsimmer McCoy. “It's a testament to the grit of the people who live in Miami,” McCoy says. “This isn't just a one-time story about displacement but a cycle that constantly happens, pushing people and forcing them to be nomadic.”

“Gentrification is almost a kind word down here,” Murray says. “It’s really displacement, almost to the level of urban renewal, because it's happening so quickly and affecting artists and working-class people.”

“As a visual artist, it has been an exciting and, at the same time, very troubling time of growth and change,” says the artist and Miami native Charles Humes Jr. “The growing number of museums, galleries and donors are now offering wonderful opportunities for artists, especially artists of colour, and that has been a great thing. But it's very difficult for artists of colour to afford studio spaces, to stay and work here.” Humes’s work highlights the displacement and loss of culture caused by gentrification in his neighbourhood of Liberty City, one of Miami’s historically Black communities, as well as issues like homelessness, racial inequity and poverty. He is participating in this year’s A.I.M. Biennial (until 14 January 2024), a showcase of site-specific and often politically minded installations throughout South Florida.

Keeping artists in Miami

“Artists have more power than we think, and if we know the rules, we can flip them or decide how to play,” Johnson says, adding that while artists can be a part of the gentrification process (like it or not), they can also choose how to engage with city commissioners and attempt to negotiate on their own terms. “We also need to be talking to each other more,” she says, emphasising the strength that comes with shared experiences and community. Johnson’s work is featured in the digital archive, book and exhibition Making Miami at Design District (until 26 December), which includes works by artists who made a beacon of the Miami arts community between 1996 and 2012.

Local arts organisations have recently been stepping up to help artists stay in Miami. In June, Oolite Arts, with support from the Knight Foundation, announced the Knight Artist Housing Stipend. Starting in 2024, the multi-year programme will give Oolite’s artists-in-residence $12,000 per year to offset housing costs. Other arts organisations, such as Locust Projects, Laundromat Art Space, and Dimensions Variable (DV), offer subsidised spaces for artists.

“We think this is great for some, but still a Band-Aid for a much larger issue,” says Frances Trombly, a co-founder and co-director of DV. She and her fellow co-founder and co-director, Leyden Rodriguez-Casanova, have discussed ideas for sustainability, grants, and property acquisition with city leaders, and the possibility of developers donating units in new buildings to artists as tax write-offs. So far, not much progress has been made.

Meanwhile, Bakehouse has a plan to expand and build more spaces for artists in the next five years. “There is an incredible need for affordable housing in rapidly gentrifying cities such as Miami,” says Cathy Leff, Bakehouse’s executive director. “All of our studios are subsidised 50% to 100%, and we want to contribute to an ecosystem so artists get more support. We are still working on it, but I know we will pull this off. We have such amazing talent in all corners of the community, and we want them to stay here.”