Henry Kissinger was one of the most consequential and controversial international political figures of his generation, and the subject of protest and satire from artists including Philip Guston and Alfredo Jaar. As US secretary of state to President Richard Nixon and then his successor President Gerald Ford, Kissinger was an agent of American realpolitik and peace-making in the 1970s, and of the US rapprochement with Communist China that led to Nixon’s celebrated visit to China in 1972 to meet Mao Tse-Tung. As part of his armoury as the world’s most high-profile diplomat, Kissinger employed “art politics” as a negotiating tool by acting in the background to secure landmark international loan exhibitions between the United States, the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China at the height of Cold War strategic arms negotiations.

As the architect of US diplomacy in Southeast Asia, and of the country’s engagement in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos—which involved mass carpet-bombing and disastrous regime change—as well as of US support of right-wing regimes in Argentina and Chile, Kissinger was the target of human rights protests for a half-century, and in 1970 a group of his former colleagues from Harvard University came to see him to suggest he resign. He was a most controversial winner of a Nobel Peace Prize in 1973, andfor the rest of his life ran the risk of being called a war criminal to his face even in the refined international social circles in which he mixed.

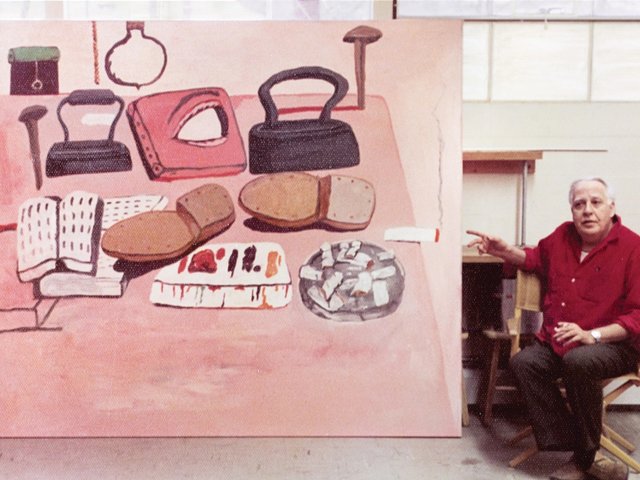

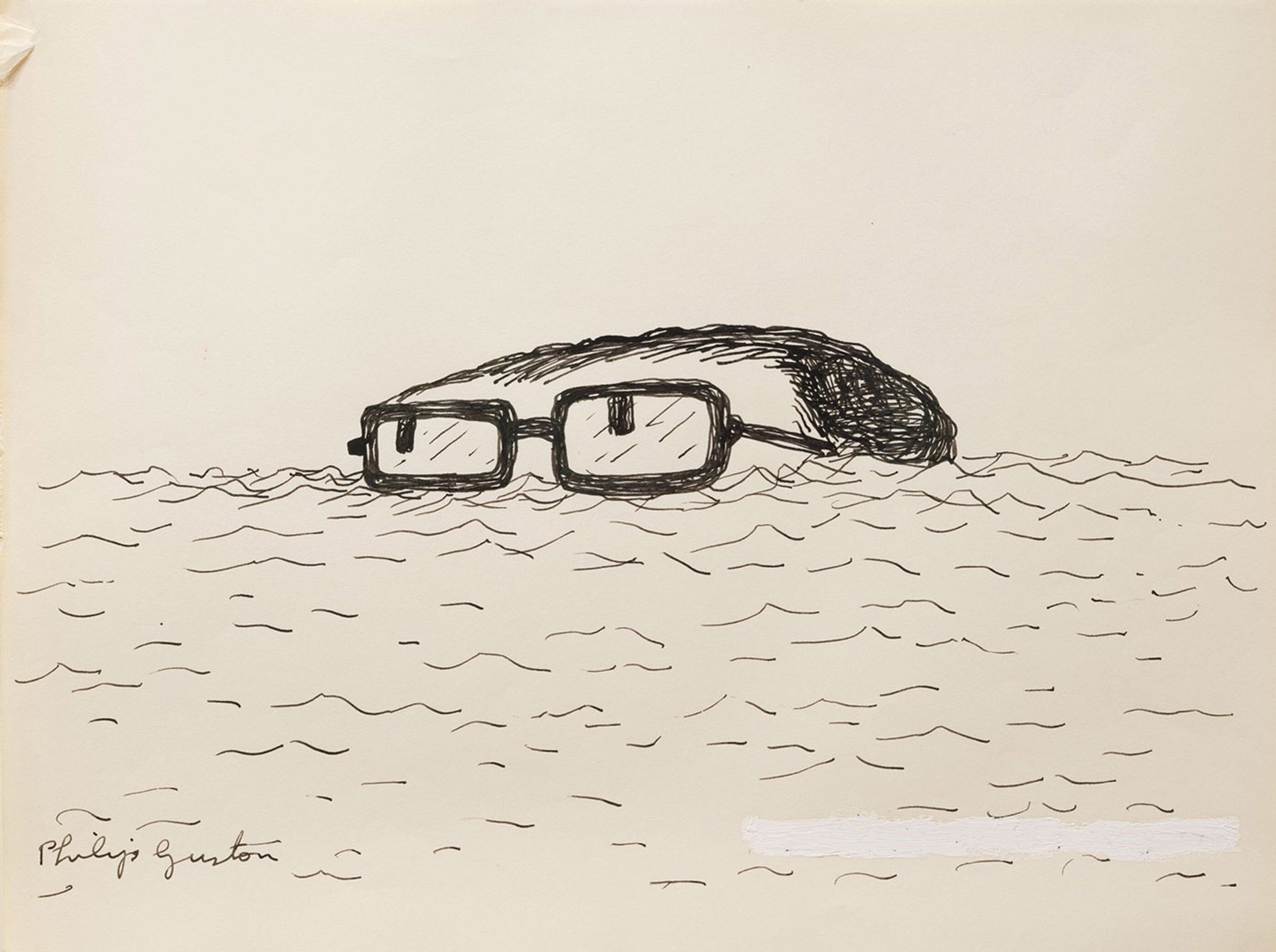

In the 1970s—an era noted for standout eyewear sported by the likes of the artist Andy Warhol and the rockstar Elton John—Kissinger’s broad-framed spectacles held their own as an instantly recognisable graphic device. In his 1971 drawings of Nixon, Guston, disgusted at US engagement in Southeast Asia, represented the president as a scrotum and penis—three years before Nixon resigned in disgrace after the Watergate affair—while Kissinger was depicted as a disembodied pair of thick-rimmed spectacles. The biting Nixon and Kissinger drawings were inspired by Guston reading some early chapters of his friend Philip Roth’s book Our Gang (1971), the satirical tale of Trick E. Dixon. These drawings were the subject of an exhibition, Philip Guston: Laughter in the Dark, Drawings From 1971 & 1975, at Hauser & Wirth, New York, in 2016.

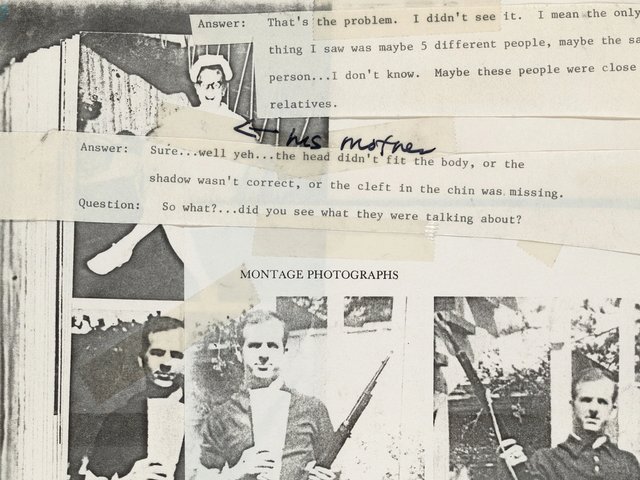

Kissinger was a staple of illustrators’ cover drawings for the news magazines Time and Newsweek, including a “Superman” cover of the latter in June 1974, at the height of the Watergate scandal, when Kissinger was often Nixon’s only confidant as the president’s time in office drew to an end. In a 1972 cover cartoon for National Lampoon magazine, Robert Grossman depicted Kissinger as Jiminy Cricket balanced on the tip of the much-elongated proboscis of Nixon as Pinocchio. In Searching for K (1986), the Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar appropriated pages from Kissinger’s memoirs to track his role in the overthrow of democracy in Chile in 1973, and the rise to power of General Augusto Pinochet. Most searing of all is a painting by the artist Charles Shobe, co-founder of the National Veterans Art Museum in Chicago, of a skeleton dressed in US army fatigues and helmet, titled Waiting for Henry Kissinger (before 1995).

Henry Kissinger (was satirised by Philip Guston in a series of drawings—including Untitled, 1971—in which the then US national security adviser is represented by a disembodied pair of his trademark thick-rimmed spectacles © The Estate of Philip Guston; Courtesy the Estate and Hauser & Wirth

In the early 2000s, the artist Jan Frank produced a series of canvases featuring Guston-style renderings of the former secretary of state’s thick-framed glasses, collectively entitled The Nixon Suite. In 2009, The Art Newspaper reported that “when Frank heard that Mr Kissinger was in New York, in order to be photographed by his old friend Steve Pyke, the New Yorker staff portraitist, Frank ... managed to wheedle his outsize—canvas up to the photography studio and thus, finally, the politician was photographed by Pyke right in front of the glasses painting”.

In his memoir Palimpsest (1995), the American writer Gore Vidal—a satirist who admittedly never let the truth get in the way of a good punchline—describes encountering Kissinger in Rome on an evening when the Italian industrialist Gianni Agnelli had taken over the newly restored Sistine Chapel, followed by a dinner in the Hall of the Statues in the Vatican. “As I left [Kissinger] gazing thoughtfully at the hell section of [Michelangelo’s] The Last Judgement,” Vidal writes, “I said to the lady with me, ‘Look he’s apartment hunting’.”

A son of Bavaria

He was born Heinz Kissinger in 1923 in Fürth, a Bavarian village. Following the Nazi party’s rise to power a decade later, he found himself the subject of antisemitic bullying at school, and his family fled Germany in 1938, first to London and then to New York, where they set up home in Washington Heights.

Kissinger made a brilliant reputation as a Harvard academic, where his Harvard International Seminar helped build his global connections. Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy (1957) was his first best-seller, while his study of the Congress of Vienna, A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812-22 (1957), elaborated a “great-man” view of history, which fed through into his life as the most influential diplomat of his day, when he traded on one-to-one connections and secret negotiations.

Kissinger’s political mentor was Nelson Rockefeller, art collector, liberal Republican, heir to a great oil fortune, long-time governor of New York and vice-president in the Ford administration. In 1994, John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s former chief adviser on domestic affairs, recalled that Kissinger hung an all-blue Mark Rothko painting in his office during the Nixon years. “Henry said it came from Rothko,” Ehrlichman told The New York Times. “We all assumed it came from Rothko’s patron, Nelson Rockefeller.”

Kissinger’s use of art for diplomatic purposes came to the fore following his first visit to China in 1971. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met), New York, were vying to host what became The Exhibition of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China (1974-75). It rankled with officials at the Met that they were scooped on this show. They asked Kissinger to help resolve an impasse in securing the finest gold objects for an upcoming loan show, From the Lands of the Scythians (1975), which he did by having it mentioned in the communiqué on the final 1974 summit meeting between Nixon and the Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev—after which arrangements went smoothly.

After the Yom Kippur War of 1973, which caused Egypt to break off diplomatic relations with the US, Kissinger embarked on a round of shuttle diplomacy to bring peace between Egypt and Israel, a strategythat had its “art politics” element in his involvement in finalising the agreement for the exhibition of Egypt’s treasures of Tutankhamun—which had been shown in London in 1972 and the Soviet Union in 1974—to go on a tour of the US in 1976.

When, 20 years later, Thomas Krens, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, was planning an ambitious loan show, China: 5,000 Years (1998), he called on Kissinger for help when negotiations had stalled and it appeared the museum might receive fewer than half of the objects it hoped to borrow from China.

After leaving office in 1977, Kissinger won a multi-million-dollar advance for his memoirs, in a Churchillian bid to write the first draft of recent history. So voluminous, and voluble, were the books—Kissinger was an equally unstoppable speaker, with a German-accented bass monotone—that the composer John Adams and his collaborators on the opera Nixon in China (1987) toyed with taking revenge by making Kissinger a silent character.

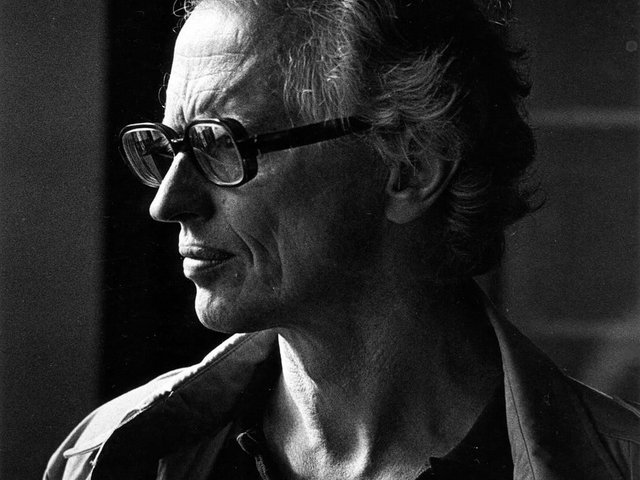

Kissinger was one of the most photographed figures of his day. Kissinger the man about town was caught hugging the actress Elizabeth Taylor by Andy Warhol in 1976; Kissinger the mover and shaker, and chairman of the North American Soccer League, was captured by Lisl Steiner in 1977 hugging Pelé in the changing room after a New York Cosmos game. When Richard Avedon took Kissinger’s photograph in 1976, Kissinger asked him to “be kind”. “I would have liked to have asked him what he meant by that,” Avedon told the writer Alain Elkann in 2014. “Should I have made Kissinger younger, taller, or thinner?”

Kissinger and his second wife Nancy Maginnes were fixtures at New York art world events at the Met and the Museum of Modern Art, living in style in River House, a stately co-op, their collection including Impressionists and works connected to his time in office, including those of the Chinese figurative artist Chen Yifei. Kissinger was back in China in 2023, honoured by Xi Jinping and his regime, half a century after the Nixon visit. He remained a polarising figure to the end, loved or reviled in equal measure around the world.

Heinz (Henry) Alfred Kissinger; born Fürth, Bavaria, 27 May 1923; US national security adviser 1969-75; US secretary of state 1973-77; Nobel Peace Prize 1973; married 1949 Ann Fleischer (one son, one daughter; marriage dissolved 1964), 1974 Nancy Maginnes; died Kent, Connecticut, 29 November 2023.

Update: this article was updated on 21 December 2023 to take in mention of Kissinger's role in art politics from the 1970s onwards, and to add consideration of other practitioners who used art to satirise him.