Storage was, until recently, an archival issue for museum directors in Iceland and the world over—firmly down the list of priorities.

But the recent news of The British Museum’s storage issues—George Osborne, the museum’s chair, last month described the loss or theft of thousands of artefacts as an “inside job”—has spread across the global museum sector.

Freedom of Information requests in the UK have since revealed that thousands of other artefacts held by UK cultural institutions have gone missing, including, in Scotland, a priceless Rodin sculpture.

The fallout of the British Museum scandal is on the minds of museum directors in Reykjavik, the tiny capital city of Iceland, thousands of miles from London. With winter coming, the directors of the country’s many museums and galleries are lobbying their government for better quality storage facilities, so they are fully able to account for their holdings and can ensure their collection is safe.

The National Gallery of Iceland occupies three locations in the Icelandic capital, making it the country’s largest visual art institution. The largest of the three spaces, on the banks of the Tjörnin lake in downtown Reykjavík, has recently opened a new gallery dedicated to the fantastical works of the Icelandic painter Jóhannes S. Kjarval.

It is a good time to work for the gallery. In 2022 the institution was bequeathed more than 1,400 works from a private Icelandic collector, which includes 400 works by Kjarval.

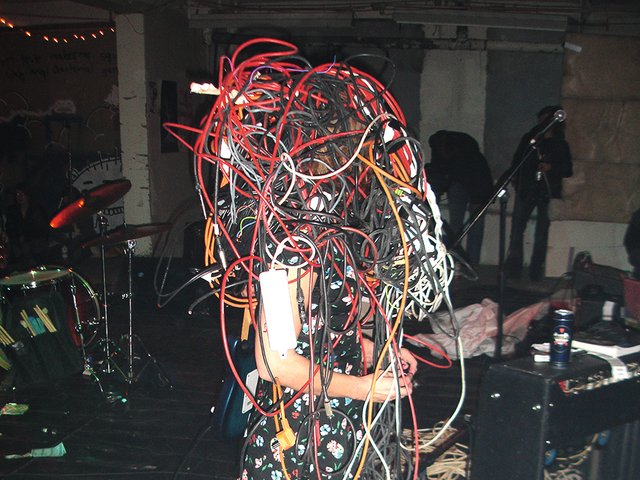

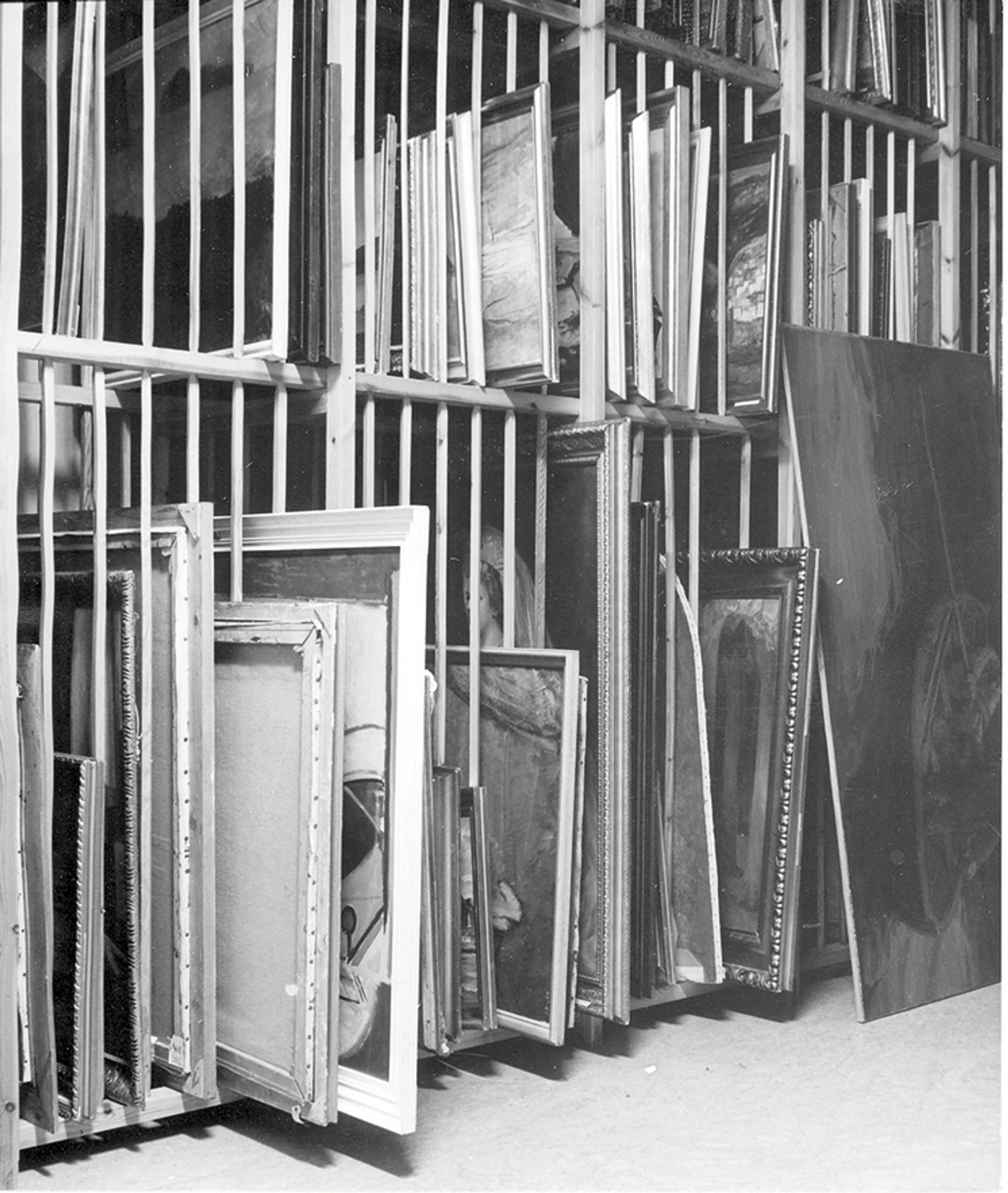

For now, the art at Iceland’s National Gallery art rests on racks in a lecture theatre Courtesy of the National Gallery of Iceland

The donation came to the gallery from the collection of the late Þorvaldur (Thorvaldur) Guðmundsson and his wife Ingibjörg Guðmundsdóttir, known as the owners of one of Iceland’s most significant and extensive private art collections.

From fisherman to famous artist

Kjarval (1885-1972) is a figurehead for Icelandic art. Born into rural poverty, he spent his early adulthood working as a fisherman and only painting in his spare time. On his first trip abroad, to the UK in 1911, he saw the works of J.M.W. Turner and William Blake in The National Gallery in London. The experience pushed him to leave his rural Icelandic life to study art at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts on a scholarship. He grew to become Iceland’s most revered artist of the last century.

Kjarval is “pivotal” to Iceland’s art history, says the gallery’s director, Ingibjörg Jóhannsdóttir, who assumed her post six months ago in April 2023. And yet Kjarval’s work has never been curated so as to be understood within the full sweep of Iceland’s history of modern and contemporary art.

“I want the permanent collection at the National Gallery to tell the story of our art history in a cohesive way,” she says. “This work has never been done before. And I would like the collection to address issues that are current, and demanding of us to think about. But, to do that, we need more space.”

We have been reading about the British Museum and it shows how key storage is for museumsIngibjörg Jóhannsdóttir, director, National Gallery of Iceland

The Guðmundsdóttir donation has also caused concern, for the museum has nowhere to adequately store the holdings. Many of Kjarval’s paintings are at present held in what was formerly the gallery’s only lecture theatre. “We have had no choice but to put up shelves in there,” Jóhannsdóttir says. “That’s the only way we’ve been able to receive the donation. We have been reading about the British Museum and it shows how key storage is for museums. It is very high on the agenda for us.”

Jóhannsdóttir is lobbying Iceland’s culture minister in the hope of finding a facility that will enable the works to be stored securely—and protect them from Iceland’s often brutal weather.

“There are practical things that need to be in better order,” she says. “The places where we are storing our artworks are not as they should be. We have to continue collecting, and we have to be able to take new things on, and, to do that, we need adequate storage space.”

In the 15 years since the financial crash of 2008, Iceland’s central government has struggled to allocate funds towards culture. It has, as a result, expected museums like the National Gallery of Iceland to make do and mend, often in difficult circumstances. “There’s some years [that] the funding for culture from the government is so low—we just can’t believe it,” Hekla Dögg Jónsdóttir, a professor of fine art at the Iceland University of the Arts. “Funding is so tied to the economy. We’re just a tiny pebble in the middle of the Atlantic ocean, with this micro-economy, and if the economy dips, funding to culture goes. We have to ride these waves.”

Local museum with global reach

On the other side of the harbour from The National Gallery of Iceland is a very different institution. The Living Art Museum is this year celebrating 45 years of existence, making it the longest running artist-run cultural institutions in Iceland. The museum at present exhibits in Marshallhúsið (Marshall House), a former herring factory that now houses a restaurant, a number of art galleries and, on the top floor, the artist Olafur Elliason’s studio. It is also is a key venue for Sequences Biennial, the contemporary art festival that celebrated its 11th edition in October. But the museum has a long history in Iceland, manifested in an archive that tells the story of Icelandic contemporary art stretching back half a century. Sarah Lucas, the British artist with a retrospective now on at Tate Modern, is among the high-profile artists who have exhibited at The Living Art Museum. Other internationally famous names to show there include Nam June Paik, John Cage, Ragnar Kjartansson and Joseph Beuys.

The museum’s archive is in the outskirts of Reykjavik in the ground floor of an industrial warehouse of what was formerly a wholesale bakery. A sodden mattress, left by a fly-tipper, lies slumped outside of the depot. Inside, pipes that brought running water to the bakery, and now in some disrepair, run malevolently above the works in situ.

Sunna Ástþórsdóttir, the director of The Living Art Museum, is proud of the archive. She lovingly searches through the archive’s treasures, unfolding an original poster, dating back to the 1965, of an exhibition of new works by a young Nam June Paik, or the twisted beer cans that Sarah Lucas turned into a sculpture, signing her name on the tin.

But Ástþórsdóttir is also lobbying the government. “A conservator from the museum council came here on a visit, looked around, and gave us a top review,” Ástþórsdóttir says on a tour of the archive. “But come on guys, look!” She points at the ceiling, with its hints of creeping damp. “I think we can do better.”