Tate Britain’s Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990 has been a long time coming. Astonishingly, the show marks the first time in its history that Tate has presented a serious survey of British feminist art; and according to its curator Linsey Young, this gathering of the work of more than 100 individuals and collectives—many having their first public showing in decades—marks “the largest exhibition to be held at Tate Britain by some margin”.

It is also mould-breaking in form, content and spirit. With refreshingly un-institutional candour, Young states that “despite its scale and ambition, and the years of love and attention that have been poured into it … I already know that it is a failure”. But this is no indictment of Women in Revolt!, but rather an honest acknowledgement that any attempt to arrive at what the Black British feminist writer Lola Olufemi describes as a “binding universal” is doomed to failure. Instead, as Olufemi puts it in the excellent exhibition catalogue, “we must roll with the messy tangled desires of our community, embracing the myriad positions we take in our fight for equality”.

Crackling subversiveness

Rolling with the messy lies at the core of this energetic, angry but also joyful show, where art and politics tangle in multiple and uncategorisable ways. Exhaustively—and sometimes exhaustingly—feminist artworks in multifarious media from across communities and cities encompass and intersect with myriad movements and causes: civil rights and racial discrimination, punk rock, lesbian, trans and gay rights, demands for better working conditions and health care, as well as environmental sustainability and nuclear disarmament, with the legendary Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp front and centre. Sometimes furious, sometimes hilarious, often coruscatingly critical but also exuberantly celebratory, Women in Revolt! crackles with a subversiveness rarely encountered in a museum survey. In these galleries, as in real life, information, art and activism mix and merge.

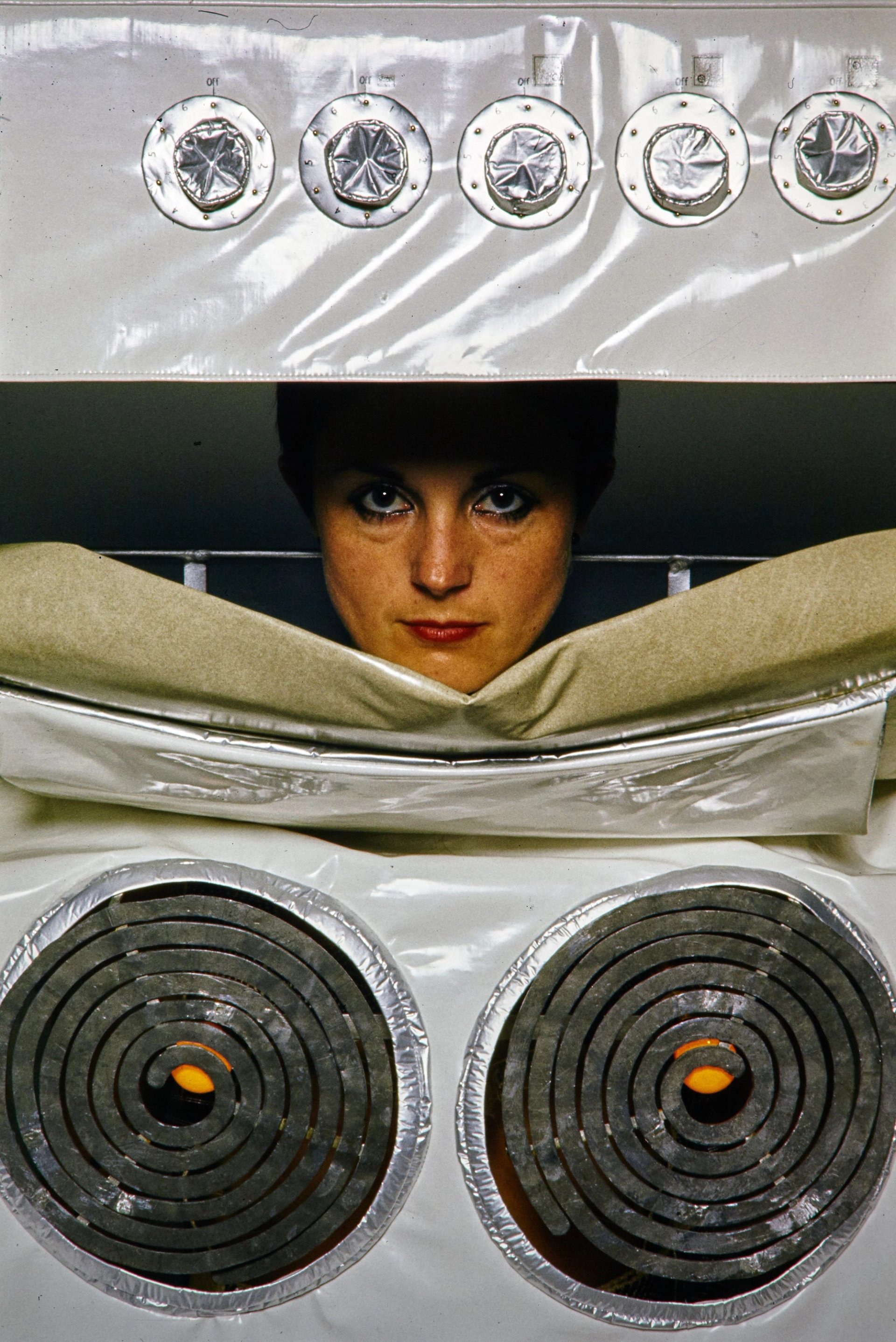

Helen Chadwick's In the Kitchen (Stove) (1977) © The estate of the artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London and Rome

Forget Gaia Goddesses and spiritual woo-woo, here the emphasis is on harsh reality and everyday injustices, with notoriously neglected themes such as domestic labour, motherhood, sex and childcare foregrounded. The gritty take-no-prisoners gauntlet is laid down in the first image of the show, Mother and Child at Breaking Point, a powerful 1970 painting by Maureen Scott of a dead-eyed, exhausted mother clutching a writhing, shrieking toddler. Never mind the chakras, these women are firmly rooted in the daily grind. Helen Chadwick encases herself in kitchen appliances with hot ring breasts and machine drum belly, Penny Slinger presents herself as an open-crotch wedding cake while Linder Sterling performs at the Hacienda club in a meat dress and thrusting dildo. Caroline Coon paints conviviality amongst sex workers, while Melanie Friend makes a powerful study of desperate but proudly defiant teenage mothers. Lubaina Himid paints a white man on a unicycle dangling a carrot in front of a Black woman, and Liz Rideal brings herself to orgasm in a photobooth.

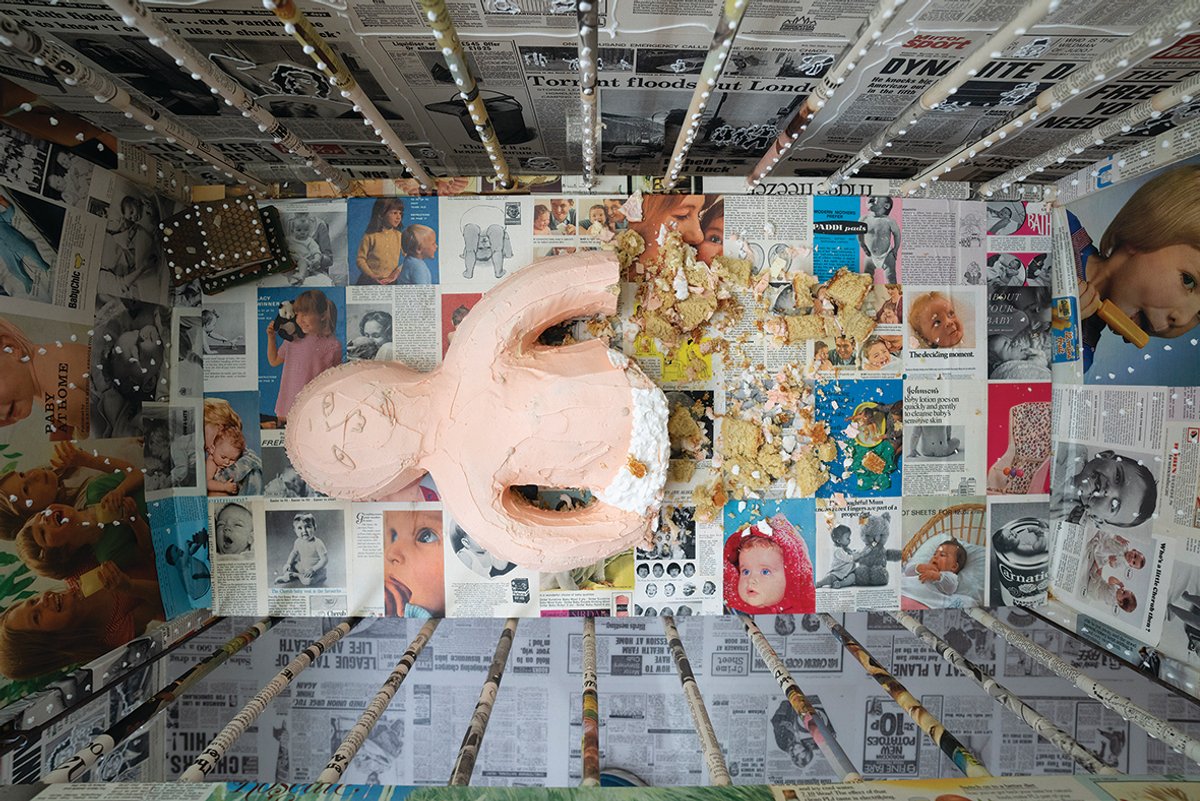

Repeatedly, Tate Britain’s revolting women spike their protests with an abundance of humour. One of the most audaciously brilliant exhibits is outside on Tate Britain’s lawn, where you can literally eat the patriarchy in Bobby Baker’s reconstruction of her legendary 1976 An Edible Family in a Mobile Home. This consumable Gesamtkunstwerk, presents a life sized family made from cake and biscuits inhabiting the early 1960’s pre-fabricated house where Baker originally presented the work in Stepney, east London, where she also lived. As well as the edible figures, the house’s walls, floors and ceilings are papered with newspapers and magazines from the time. A meringue daughter hovers above her bed surrounded by spreads from Jackie magazine, a Garibaldi-biscuit son lies in a bathroom lined with Marvel superheroes while in a sitting room plastered with the contemporary tabloid press, a fruit cake Dad watches TV accompanied by a coconut sponge baby and presided over by Mum, a pink dummy with teapot head and refillable body compartments bursting with replenishable snacks, who dispenses constant food and comfort.

Portrait of Bobby Baker with Edible Family

© Tate. Photo: Madeleine Buddo

Visitors are encouraged to help themselves to these elaborate confections, leaving just crumbs and grotesquely disfigured remains. Only Mum keeps offering nourishment. For Baker, the original intention was to make a work that was “local and accessible”, to be consumed by the families surrounding her home, rather than an art world she found “elitist and extremely macho”. It took her by surprise when the piece turned unexpectedly personal. “It wasn’t intentionally autobiographical, and I didn’t realise until I saw this devastated family that I’d made my own family,” she tells me.

Although Baker’s Edible Family is in one sense a period piece, it is also by its very ingestible nature part of everyone’s here and now. “It’s about what is happening in people’s lives—the strength and importance in just living,” she says of her recreation. Like so much of Women in Revolt!, this generous, serious, funny work is both of its time and also utterly relevant to today’s world. In the UK right now, women are still lower paid in the workplace, continue to be assaulted by men and are threatened by crises in public health, housing and the cost of living. This crucial, inspirational show underlines that now, more than ever, women are still in revolt.

• Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990, Tate Britain, London, until 7 April 2024