The autumn auction season made another stop along its largely middle-of-the-road journey through New York on Tuesday (14 November), as Phillips generated $128.1m ($154.6m with fees) across its dual evening sales, modestly below the combined presale estimate range of $146m to $193.6m (calculated without fees).

But the deeper one looks into the evening’s mixed results, the clearer it becomes that a sale (and an auction season) as a whole often reaches the median only by powering up some lofty peaks and enduring some deep ditches.

Case in point, despite its middling performance relative to the presale estimate, the dual sales’ total qualified as the second-highest single-night tally in Phillips’s history. It also represents an 11% year-over-year improvement on the total sales figure from the equivalent evening auction in November 2022. A few individual highlights shined through, too: the house posted the fourth-richest price ever achieved at auction for a Gerhard Richter painting, at $30m ($34.8m with fees), and set a new record for the in-demand British painter Jadé Fadojutimi, at $1.55m ($1.9m with fees).

An overview of Phillips’s financial guarantees nonetheless suggests the decision-makers felt significant anxiety leading up to the opening of bidding. In total, 39 of the 56 lots to actually cross the block (69.6% by volume) carried a house guarantee—and Phillips minimised its risk by securing third-party backers for all 39 of those lots. The aggregate low estimate for the guaranteed works added up to $119.5m, a figure only $8.6m lower than the $128.1m hammer total for both sales.

Counting the four withdrawn lots and two passes, Phillips found buyers for 54 of the 60 works originally scheduled to be offered on the night, good for a robust 90% sell-through rate. (Excluding the quartet of withdrawals raises that figure to 96.4%.)

“This could have gone quite differently for us,” says Robert Manley, Phillips’s deputy chairman and worldwide co-head of 20th century and contemporary art. “If all the houses were being brutally honest, we’d say we were nervous going into the last two weeks, with all the turmoil going on in the world. But for the most part we’ve been happy to find that collectors have been active and engaged.”

Below, a breakdown of each of Phillips’s two sales: Living the Avant Garde: The Triton Foundation Collection and the 20th-century and contemporary art evening sale.

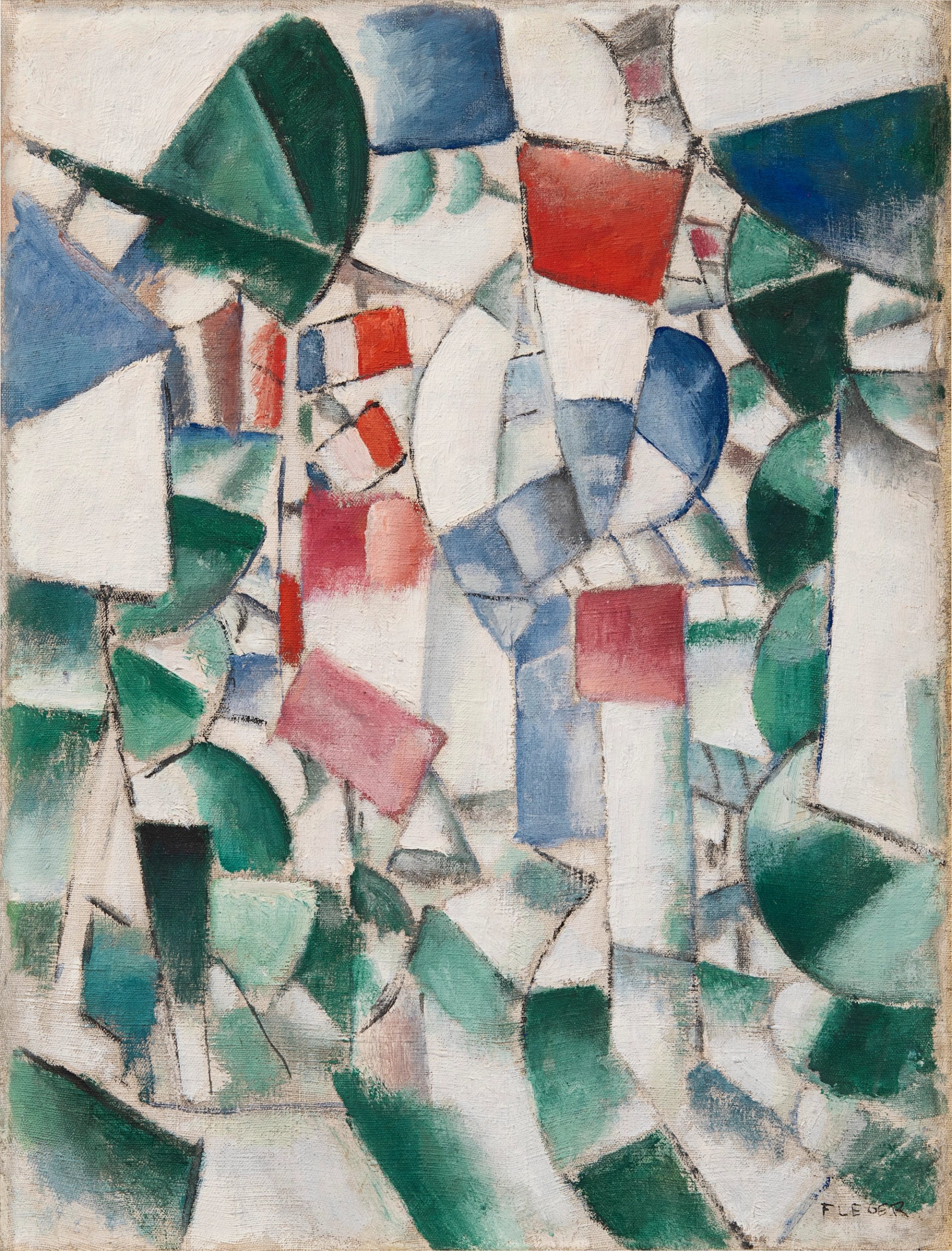

Fernand Léger, Le 14 juillet ou la maison sous les abres, 1912-13.

Courtesy of Phillips.

Living the Avant Garde: The Triton Collection Foundation

The evening commenced with a dedicated offering of 30 works from the Triton Collection Foundation, an enterprise begun by the Dutch shipping and oil magnate Willem Cordia and his wife, Marijke van der Laan. After Cordia’s death in 2011, the couple’s art holdings were transferred to a foundation that is now controlled by their two children, who consigned the works to Phillips to fund new acquisitions more in line with their own taste.

The Triton group was fresh to market, with “the vast majority” of the works offered having never before appeared at auction, according to a Phillips spokesperson. Only three of the 30 works had gone under the hammer in the past 20 years.

The Triton lots ultimately took in nearly $69.9m ($84.7m with fees), just shy of their cumulative $73.3m low estimate. Phillips guaranteed the foundation an undisclosed minimum price for the 30 works. The house later secured multiple third-party guarantors to cover the entire group. This maneuvering ensured that the collection would be a white-glove sale (meaning 100% of lots would sell) before the bidders in the New York saleroom even took their seats.

There were no surprises when it came to the identities of the Triton Collection Foundation’s top lots, either. The two highest prices achieved belonged to the only two works expected to sell for at least $15m. Both lots also found their price level quickly, with the bidding for each lasting less than two minutes.

Pablo Picasso, femme en corset lisant un livre, 1914-18.

Courtesy of Phillips.

Fernand Léger’s Le 14 juillet ou la maison sous les arbres (1912-13), a Cubist perspective on a Bastille Day celebration with multiple French flags flying, hammered at its $15m low estimate and reached $17.6m with fees. (The reverse side of the canvas bears a second complete work, from the artist’s Fumées sur les toits series depicting the modernising Paris skyline from his studio window.)

Six lots later, auctioneer Henry Highly knocked down Picasso’s Femme en corset lisant un livre (1914-17), a colourful later development in his Cubist era that depicts his lover Eva Gouel, at $12.5m ($14.8m with fees).

Two other Triton works hammered for more than $5m. The first, a compositionally frantic but chromatically subdued Georges Braque painting titled La bouteille de Bass (1911-12), found a buyer at its $7m low estimate (the price with fees was $8.5m). The other, an untitled Joan Mitchell canvas from 1954, went to a phone buyer on the line with Miety Heiden, Phillips’s head of private sales, who won it on a bid of $6.5m ($7.9m with fees), beneath its $8m low expectation.

Of the 30 Triton works, 19 hammered at or below their low price targets, including ten of the last 11 lots in the sale. But the final work, Sam Francis’s Purple, Orange & Green (1958), ended the first half of the evening’s proceedings on a high note. The painting nearly doubled its $200,000 low estimate, finding a buyer at $380,000 ($482,600 with fees).

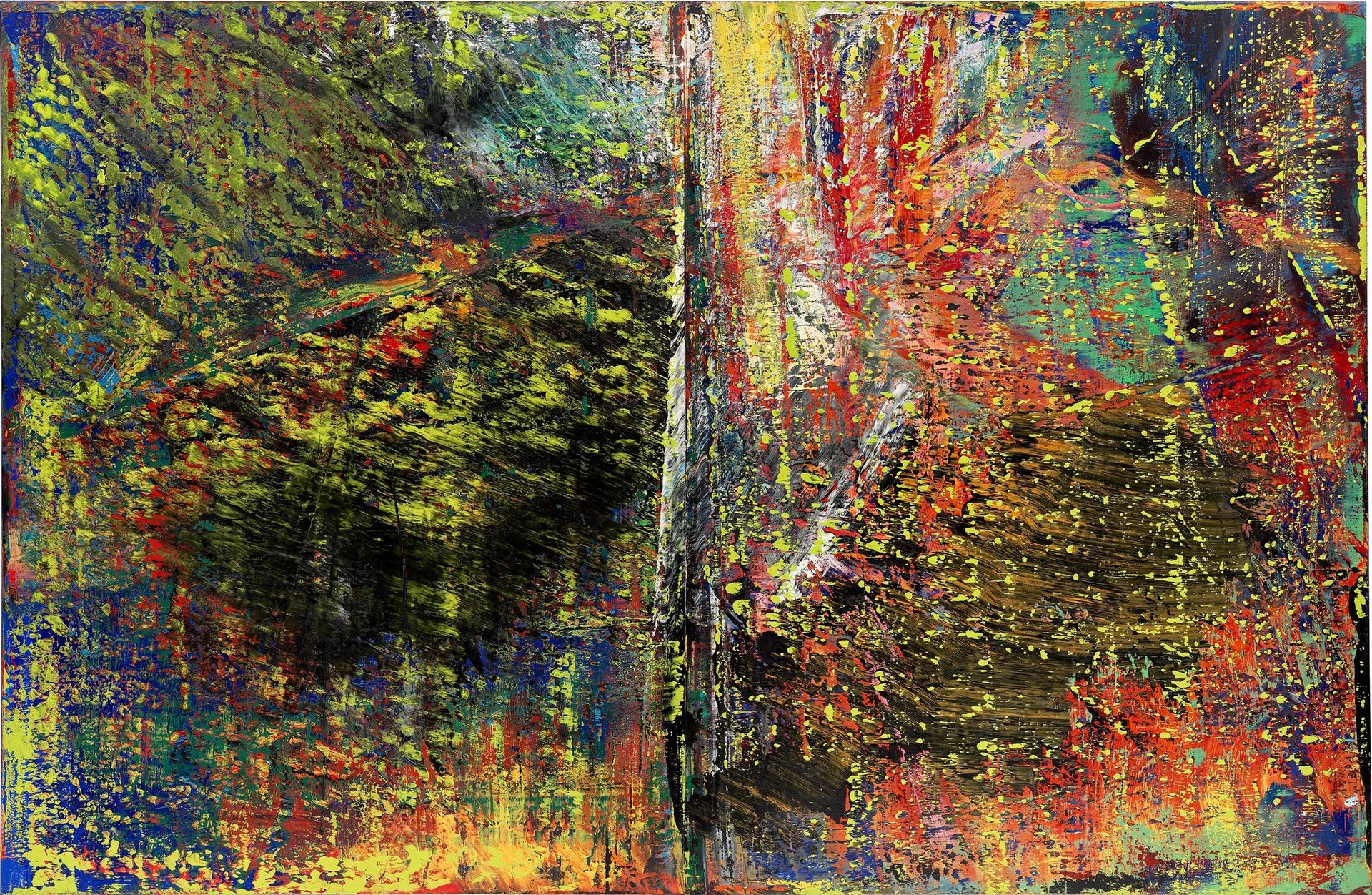

Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild (636), 1987

Courtesy of Phillips.

The 20th century and contemporary art evening sale

The evening’s second half performed slightly worse vis-à-vis presale expectations than the Triton collection. The hammer total of $58.2m ($69.9m with fees) fell short of the original low estimate of $72.7m by 20%. It also missed (albeit barely) the revised low price target of $60.5m after the house expunged the four lots withdrawn from the sale.

One of those lots in particular took a huge bite out of the bottom line: Joan Mitchell’s Blueberry (1962). The painting carried an even higher estimate ($9m-$12m) than the earlier work by the artist offered as a part of the Triton collection. With Blueberry removed from the lineup, however, Phillips needed a bidding war to ignite for at least one of its other top lots—and none did.

The two lots bought in were each relatively low value: Lynne Drexler’s 1969 landscape Seasonal Green (1969) passed at $280,000 against a $300,000-$500,000 estimate; and a magenta Jeff Koons Balloon Venus sculpture from 2013-17 passed at $2.4m against a $3m low target.

Joan Mitchell, Blueberry (1962)

Courtesy of Phillips

The biggest success by value on the evening was the aforementioned Richter diptych, Abstraktes Bild (636). Painted in 1987, the work carried an unpublished presale estimate in the region of $30m. That number was where the winning bid landed after approximately three minutes of subdued competition, with fees lifting the final price to $34.8m. The second-priciest work sold in the second half of the evening, Georg Baselitz’s Ein Roter (1966), also hammered at its low estimate, making $6m ($7.3m with fees).

The most propulsive bidding was stoked by some of the youngest artists in the sale. The first lot of the post-Triton group marked the evening sale debut of Canadian painter Ambera Wellmann, whose Cecily Brown-esque composition of entangled nudes hammered at $105,000 ($133,350 with fees), roughly two-and-a-half times its $40,000 low estimate. That result was followed by a 2020 Lucy Bull abstract knocked down for $820,000 ($1.04m with fees), more than double its $400,000 low target. And Fadojutimi’s earlier-mentioned record-setter, Quirk my mannerism (2021), hammered at $1.55m, nearly double its $800,000 high expectation.

Asked about the difference in climate for up-and-coming talent on the secondary market compared with a year ago, Manley says: “In general, there’s a little more realism out there.” To him, the results for the evening's works by Wellmann, Bull and Fadojutimi mean the market is “in a very good place”, adding: “They’re selling, but not for prices higher than Joan Mitchell or Picasso.”

Jadé Fadojutimi, Quirk my mannerism, 2021

Courtesy of Phillips

There is one more night for the Big Three auction houses to put a more positive spin on the season. The nocturnal segment of New York’s autumn auction cycle closes Wednesday (15 November), with Sotheby’s double-header of The Now and Contemporary evening sales. But Phillips’s most important work is done, and Manley, for one, is satisfied with the outcome—though not complacent about the future.

“I’ll be happy on Thanksgiving to appreciate what we’ve accomplished and then get back into the trenches,” he says.