In 1989 the artist Rasheed Araeen issued a challenge to the British art establishment in the form of an exhibition. The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain at London’s Hayward Gallery featured 24 artists of Asian, African or Caribbean heritage (including Karachi-born Araeen) who had made careers in the UK but were still, he contended, racially excluded from the “citadel of Modernism”. Leading newspaper critics were sceptical, even scornful, with one concluding: “For the moment, the work of Afro-Asian artists in the west is no more than a curiosity, not yet worth even a footnote in any history of 20th-century western art.”

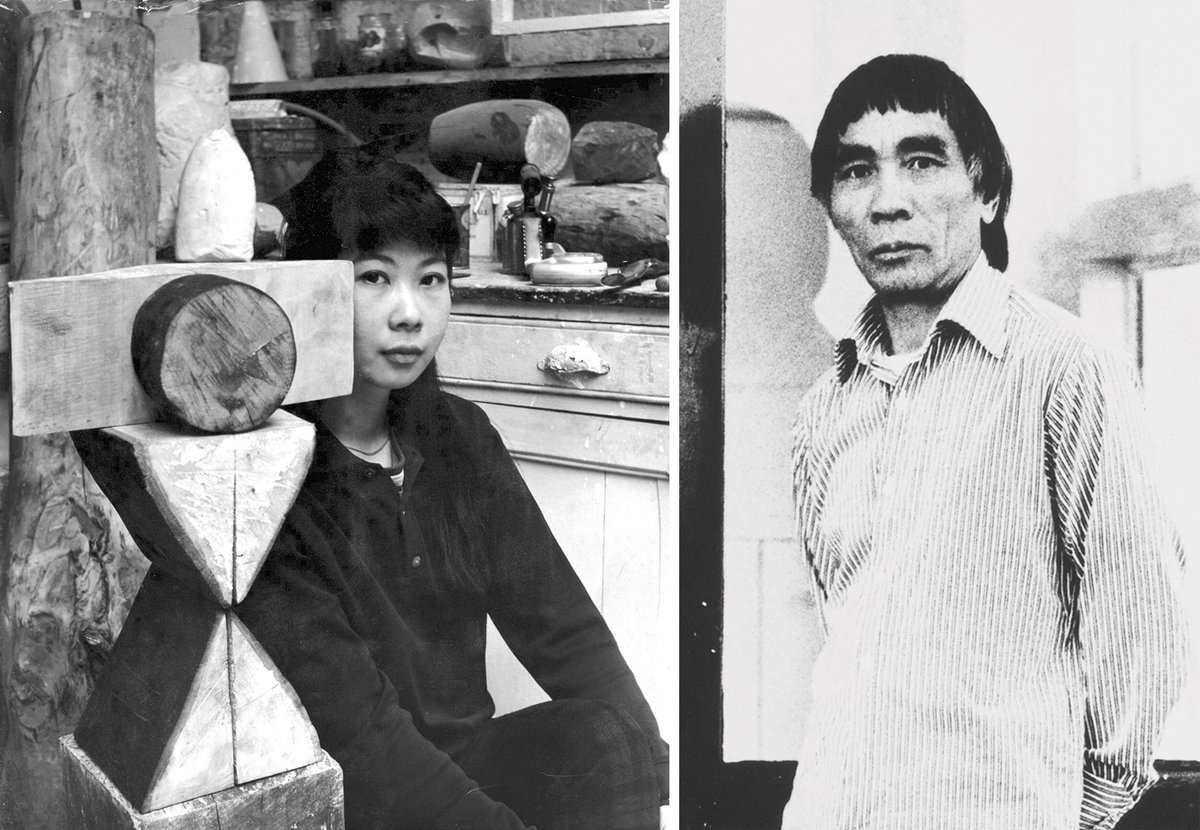

Today is another story. Two bastions of Modern British art are now devoting exhibitions to diasporic artists who were connected, in different ways, to The Other Story exhibition: Li Yuan-chia (1929-94) at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge and Kim Lim (1936-97) at the Hepworth Wakefield.

Li had an itinerant life from a young age, shuttling between orphanages and military schools in mainland China. He moved in 1949 to Taiwan, where he joined the Ton Fan group of abstract painters. The 1960s took him to Italy, London (via an invitation from the radical Signals gallery), and eventually to the Cumbrian village of Banks, in the borderlands of Hadrian’s Wall, where he settled. In a rundown farmhouse bought for £2,000 from the painter Winifred Nicholson, he built and ran a museum bearing his initials and boundless creative sensibility: LYC Museum and Art Gallery.

Lim’s bronze sculpture Pegasus (1962); later in her career she moved on to working with stone © Estate of Kim Lim / Turnbull Studio. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2023. Photo: Mark Dalton

Its programme was hyperactive, involving more than 300 artists between 1972 and 1983, from Audrey and Dennis Barker’s locally produced replica Roman artefacts and period costume dolls to the first solo showing of Andy Goldsworthy’s ephemeral works in nature. There were performances, poetry recitals, rug-making workshops, monthly tea parties and a children’s art room. The LYC was a “bridge which different tribes could cross”, says the curator and researcher Hammad Nasar, who has co-organised the Kettle’s Yard show with Sarah Victoria Turner and Amy Tobin.

Their curatorial process has sought to channel the LYC’s “polyphonic and collaborative” spirit, he says. Development workshops convened Li’s past collaborators with scholars and artists attuned to his legacy today. Three of the participating artists have new commissions in the show: Grace Ndiritu, Charwei Tsai and Aaron Tan. This is not a reconstruction of Li’s lost museum, Nasar says, “but it’s trying to share some of the ethos”.

So Li’s multidisciplinary conceptual art—calligraphy and ink paintings, sculptural reliefs, textiles, hand-tinted photographs—will be displayed alongside works by his artist friends such as Nicholson, Takis and Liliane Lijn. Replicas of Li’s “magnetic points”, multiples that expressed the cosmic “beginning and end of all things”, will be available to interact with, as they were in the LYC art room and in The Other Story, his final exhibition.

Nasar sees a poignancy in the juxtaposition between the carefully preserved environs of Kettle’s Yard, the former home of British art collectors Jim and Helen Ede, and the oblivion of Li’s Cumbrian farmhouse, which he struggled to sell before his death. The implicit comparison, Nasar says, is a way of “thinking about who gets to be within British art history”.

Similar thoughts underpin the Hepworth Wakefield’s exhibition of the sculptor and printmaker Kim Lim, the most comprehensive ever held of her four decades of work. This is a “moment of recognition by the wider British art ecosystem”, says Bianca Chu, strategic adviser to the Kim Lim Estate, and a “celebration” that has been “a long time coming”.

Fallen from view

Born in Singapore to Chinese parents, Lim studied in London at St Martin’s School of Art and the School of Fine Art in the late 1950s and stayed for the rest of her life, “establishing a successful career that has since fallen from view”, as a press statement puts it.

The Hepworth show takes its title from her central preoccupations with space, rhythm and light. It promises to reveal the breadth of her abstract art practice through what Chu calls the “twin processes” of sculpture and printmaking. Just as Lim moved freely between the two, she drew on a wealth of cultural influences from visits to Asia and elsewhere to distil into her minimalist forms. The estate is lending rarely seen photographs she took of these travels with her husband, the sculptor William Turnbull.

A hand-coloured photographic print by Li Yuan-chia, Untitled, from 1994, the year of the artist’s death Image courtesy of the Li Yuan- chia Foundation

While Chu says Lim had an “innate understanding” of crossing cultures, she resisted being defined by either race or gender during her lifetime. “What was important in the end was what I did and not where I came from,” she stated in her personal writings. “Race and gender were givens I worked from, perhaps the work does reflect this which is fine, but I did not want to make them an issue.”

Lim broke new ground by being the only woman and only non-white artist selected for the inaugural Hayward Annual exhibition in 1977 (to some controversy, due to Turnbull’s role on the jury). But she declined Araeen’s invitation to show at the gallery 12 years later in The Other Story, writing in a letter to the organisers that “to participate would be to self-consciously place myself in a situation of ‘otherness’”.

“It says something about [Lim] wanting to feel more free, rather than being continuously put into a category,” Chu says, in a statement that could apply equally well to Li Yuan-chia’s expansive world. While Chu acknowledges that “systemic biases” contributed to Lim’s work going under-

represented in UK institutions for years after her death, the interval was perhaps “useful”. Showing it now, at a time when the “transnational” and “multidisciplinary” are common currency in global contemporary art, means the landscape is at last “ready to receive the work”.

• Making New Worlds: Li Yuan-chia and Friends, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, 11 November-18 February 2024

• Kim Lim: Space, Rhythm & Light, Hepworth Wakefield, 25 November-2 June 2024