The Central Asian Republic of Uzbekistan is best known, culturally speaking, for the ornate mosques and Islamic architecture that dot the cityscapes along the Silk Road trade route from China to the Middle East: Samarkand, Tashkent and Bukhara.

But now, the post-Soviet nation is gearing up for a series of big-ticket contemporary art museum openings and high-profile cultural events scheduled to take place over the next two years. Uzbek heritage is on show, and now, also, contemporary Uzbek art.

Some of the planned museum projects include the construction of a new State Art Museum designed by Tadao Ando Architects & Associates in Uzbekistan’s capital, Tashkent. With a collection of more than 100,000 objects, the museum, which is yet to announce an opening date, is poised to become the largest exhibition space in Central Asia, covering more than 40,000 sq. m.

Another big development is the restoration of the Center for Contemporary Art (CCA), also in Tashkent. Housed in a former 1912 diesel station and tram depot, the CCA is at present undergoing major renovation by the French architectural firm Studio KO and is expected to open its doors in 2024.

What is driving this new investment in contemporary art? Rich in natural resources, the landlocked Central Asian nation has, since 2015, been a partner in the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s multinational infrastructure programme; two of its main routes pass through Uzbekistan, as do all four corridors of the Central Asia-China gas pipeline. In addition, Uzbekistan is slowly opening up to private foreign investment and competition, and is becoming increasingly important to European partners; according to The World Bank, Uzbekistan’s GDP grew by 5.7% in 2022.

Foreign economic interest also draws heightened attention to the country’s human rights issues. As a new member of the UN Human Rights Council, the Uzbek government signed a pledge to uphold and promote human rights standards in 2021. However, according to a 2022 report by Human Rights Watch, violations of civil liberties and restriction of freedom of expression and the media are still significant, as are allegations of forced labour and torture. In a recent analysis by Reporters without Borders, Uzbekistan ranked 137th in the Press Freedom Index, a downgrade of four spots since the previous report.

International partnerships

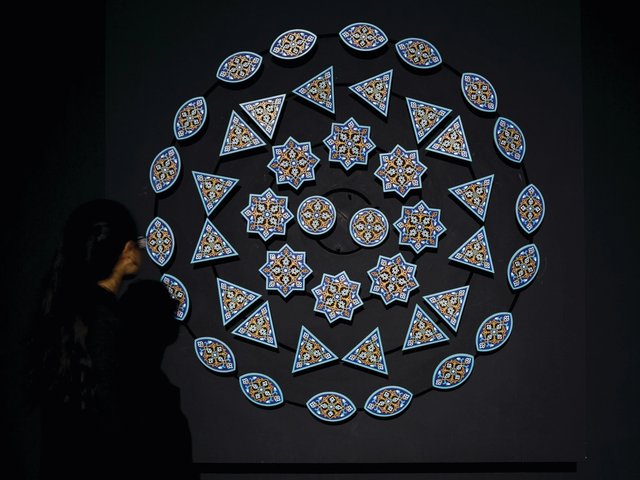

Since assuming the presidency in 2016, Uzbekistan’s President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has taken steps to implement reforms, including the protection of natural resources and heritage. In 2017, Mirziyoyev established the republic’s first government-run Art and Culture Development Foundation, which has been keeping busy ever since. Chaired by the curator Gayane Umerova, the foundation is in charge of Uzbekistan’s participation at the Venice Biennale—Uzbekistan’s first national pavilion was inaugurated at the 2021 Architecture Biennale—as well as organising international exhibitions with a network of institutional partners. The Louvre and the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, as well as Berlin’s James-Simon-Gallery, have all hosted exhibitions this year featuring Uzbek artefacts and archaeological treasures. Next year, a two-part show on the Uzbek avant-garde movement is slated to take place at the Uffizi in Florence and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. The predominantly Sunni Muslim country is also strengthening its cultural links to the Middle East; it participated in the first Islamic Arts Biennale in January and, in November, Uzbekistan will present for the first time at the Sharjah Architecture Triennial.

Umerova, who declined to comment on the Art and Culture Development Foundation’s operating budget and individual costs of museum projects, says there is a long-term strategic vision for local institutions: “Our aim is to promote a renewal of museums, ensuring that they align with international standards,” she says. “By doing so, we aspire to provide visitors with a world-class experience that reflects the richness of Uzbekistan’s cultural tapestry. Through these efforts, we’re working to create an environment where the past is celebrated, the present is enriched, and the future holds the promise of continued cultural vitality.”

Meanwhile, Nisso Yakhshimuradova, the director of the CCA, is tasked with spurring locals to engage and participate in the activities offered by the new arts hub and in establishing a new culture of arts patronage. “Currently, the contemporary art scene is experiencing a period of the gradual growth,” she explains. “But we are making efforts to ensure Uzbek artists are empowered to seamlessly integrate into the global current of contemporary art.” Ahead of its opening, the CCA is launching a residency programme in November in historic sites in Tashkent’s Old City—the Namuna and Khast Imam mahallas—also refurbished by Studio KO. Participants will have access to studios, as well as local artisan workshops and traditional knowledge.

Indeed, the Art and Culture Development Foundation has big plans for the region. In 2025, Uzbekistan will launch a new art biennial in Bukhara, a well-preserved medieval node of Islamic culture and theology. “This endeavour holds significant implications for the region,” Umerova says. “This mission isn’t confined to geographical boundaries; it encompasses both local artisans, artists and their international counterparts, fostering an exchange of expertise and insight among specialists”.

Uzbekistan is also reckoning with past mistakes and mismanaged resources through arts and culture. In March, Umerova spoke at the UN Water Conference, sharing plans for a cultural programme in the Aral Sea basin region that would tackle the challenge faced by what used to be the world’s fourth largest lake, now a desert. “Our main goal is not just rejuvenation but also to reshape and redefine the prevailing narratives of the Aral Sea’s post-catastrophic phase,” Umerova says. A key part of this will be next spring’s Aral Culture Summit, which will invite artists and architects to rethink the desert and its ecology, and hopefully contribute to improving conditions in the region.

“Vernacular architecture sees rammed earth and reeds as sources for sustainable construction; the bio-design approach allows algae and salt to become new materials that require almost zero water resources, unlike concrete,” Umerova says.

The Silk Road of today will soon be dotted with contemporary architecture, built to showcase the best new art in the region. For cultural explorers, Uzbekistan is now a key stop along this historic route, if it allows its artists to flourish, unabated.